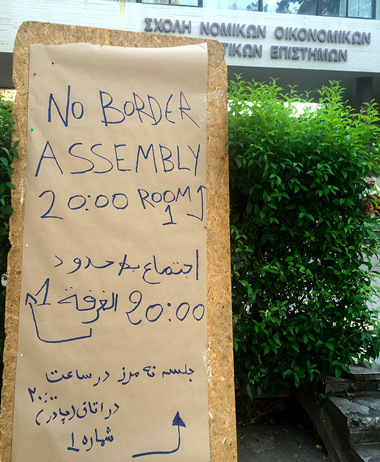

Images, notes, and quotes on and around the No Border encampment in Thessaloniki, July 2016 (rendered in the light of anarchist illegalism).

by Ernest Larsen

Continued from Part 1.

- The anti-nationalist No Border network attacks the problematic of the illegal concretely and actively, its primary slogan affirming the implied double negative: no person is illegal.

The European Union’s famously and falsely open borders continue to provide for the No Border network the con-testing ground of neoliberal ideology, the crux of which is that Capital is absolutely free to move but Labor can never be allowed that right/privilege. Scratch a right and find a privilege.

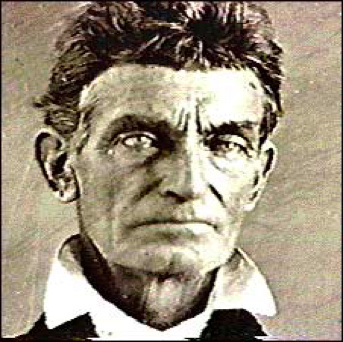

John Brown, US abolitionist executed on December 2, 1859

The call for the abolition of borders is part of a more generalized renewal of abolitionist movements: the relatively modest claim in the US that “Black Lives Matter” leads to a movement for the abolition of the police; the initial liberal call in the US to reform prisons (and drug laws) foretells the growing prison abolition movements. That which seemed virtually unimaginable at one moment later assumes the shape of a national movement.

-

At age twelve, I read Tolstoy’s final novel, Resurrection, fired up by its intransigence. The old writer, by then violently pacifist, writes the strange fiction sustained by a single unshakable conviction: We have no right to judge others.

-

Resistance culture calls for

or sets the conditions of

or imagines the conditions of

radical potentiality.

The French critic and filmmaker Jean-Louis Comolli, director of the anarchist-oriented film La Cecilia, has written: “Defeating or overcoming the existing order of things requires the invention of forms that are different to those serving to repress our consciousness and our movements.”

This is succinct, perhaps overly succinct: the requirement to which Comolli refers should, we feel, encompass the invention of forms of life, of politics, and aesthetic forms, as an intentional project that produces the conditions through which such revolutionary change could begin to be achieved. The invention of such forms, in whatever domains of human experience or knowledge, is, we venture to say, always experimental. As we approached organizing the screenings for the encampment in Thessaloniki, we hoped that the No Border events might crystallize and advance such newer forms.

For more than a decade, we have been putting together screenings of short-form experimental/political films, often in unconventional venues, such as self-managed squats and social centers in Eastern and Southern Europe—taking interventionist films to sites of self-organized intervention. (Our DVD project Disruptive Film: Everyday Resistance to Power collects many of these films.)

A New York friend, a filmmaker, asked me to write about what we were up to in Thessaloniki for the “Visible Evidence” conference on documentary film, about to be held in Bozeman, Montana, at the same time as the No Border events.

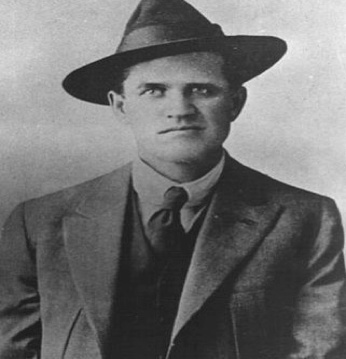

I remembered that Bozeman is not far from Butte, Montana, once the site of the notorious Anaconda Copper mine. I remembered the name of Frank Little, an organizer for the IWW, who was lynched in Butte on August 1, 1917. His grave marker reads: “Slain by capitalist interests for organizing and inspiring his fellow men.”

Frank Little

Bozeman Magazine eagerly examines this heritage (freely adapted below):

The IWW was the only American union to welcome all workers into their ranks, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians. This all-encompassing welcome of the previously excluded may well have contributed to the nickname that most IWW members carry with pride: Wobblies. The story most often told involves the Chinese owner of a restaurant in Vancouver in 1911. He supported the IWW and allowed its members to dine on credit. Unable to pronounce the letter “w,” he would ask if a man was in the “I Wobble Wobble.” Local members soon referred to themselves as part of the “I Wobbly Wobbly,” and by 1913, “Wobbly” had become an honorific nickname for workers who carried the red card indicative of IWW membership, a nickname that “hints of a fine, practical internationalism, a human brotherhood based on a community of interests and of understanding.”

(B. Traven’s early novel The Cotton-Pickers, set in Mexico, was originally titled The Wobbly.)

This is what I sent my friend in Bozeman two days after he emailed me:

In February, 2015, shortly after the first election of Syriza to power in Greece, a moment when so many Greeks’ hopes were still so high, due to the election of what appeared for awhile to be the ascendancy of a real left, we were asked to do a screening at Sabot, a rented anarchist social center in Thessaloniki. This would be the night before a major demonstration at a migrant detention center, in the town of Xanthi, near the Bulgarian border. So, under the rubric Border-Crossers, we screened seven short films to a packed and enthusiastic audience of activists. It was a memorable and, we were assured, a highly successful and even inspirational evening of political/cultural education—for us, as well as the audience.

Posters announcing the screening at Sabot

Our unvarying practice is to screen shorter films. In our experience, this allows for considerably more immediacy of discussion, often between films, and for the ferment of argument to take place or even to take over to some degree—as the films in the program jostle against each other in interesting and challenging ways. Even the next day after the Sabot screening, during the demo itself, in Xanthi, I spoke to participants with more questions and thoughts about the films. That day’s test of Syriza’s promise to close the country’s many detention centers was vigorous. However, Syriza’s promise turned out to be a massive deception, as the following months were to prove.

This July we were invited to organize a series of five screenings at the No Border occupation/camp, held for ten days, on the campus of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, Greece. Once again we constructed programs that we thought offered a wide-ranging and historically grounded examination of nationalism and the border. The films we screened reached from the Algerian revolution in 1961 to the present day in Syria and were produced in ten countries altogether.

Unexpectedly, the screenings all turned out to be open-air. The room set aside for our Disruptive Film screenings was repeatedly needed as the best site for smaller (as opposed to general) assemblies. So the world’s longest extension cord was found, a screen was stretched between two adjacent trees, two large speakers set in place by young cineastes. We provided the laptop, and a portable projector was contributed by one of the founding members of Clandestina, the long-standing migrants/anarchist group in Thessaloniki mentioned earlier. The impromptu spontaneity of all this proved to be both necessary and appealing. However, the screening did not get under way until midnight, a mere three hours late. Still another assembly had cropped up only yards away from the white screen that swayed gently in the evening breeze. From all this you might be able to guess with some accuracy that cultural commitments during the encampment did at times take second place to political necessity.

Well after midnight

When the time came round at last for a screening to begin, I would turn on the music of Tinariwen at top volume, to encourage the crowd to gather. Sherry or I briefly introduced each of the films to the notably polyglot audience lounging on the grass (or rather the weeds: the university is too strapped for cash to indulge in lawn care). All the films not produced in the English language were subtitled in English—just as the No Border workshops, all fifty of them, were conducted in English.

The encampment drew about fifteen hundred anarchists and antiauthoritarians from Italy, Germany, Spain, Britain, Denmark, and other European countries plus who-knew-how-many migrants, most of these coming from the notoriously squalid “hospitality” centers put in place by the second Syriza government, just two months earlier, on the outskirts of Thessaloniki, in abandoned warehouses and the like, housing—if that’s the word—as many as twenty thousand migrants.

There were, of course, many demonstrations during the No Border camp: at the Turkish border, at the Turkish consulate, through the streets of the city—a march led by migrants including a six-year old boy who used a bullhorn to spark the chants—and at the cruelly-named hospitality centers, where migrants were encouraged to join us at the university.

Keep in mind the overall conditions on the grounds of the university: continuous heat, hundreds of tents popped up across the campus, the all-but-constant circle assemblies and ad hoc meetings, the logistical challenges of feeding, busing, medical, and legal emergencies, etc. Imagine, if you will, “Visible Evidence” itself being held illegally at a university in Bozeman, under ceaseless attack by the mainstream media, imminent threats of police invasion, the university chancellor and the mayor of Bozeman issuing calls for law and order. During this “Visible Evidence,” all of you folks live in tents on campus, break when necessary a few locks on a few doors to gain illegal access to buildings, put up with faulty sanitation and inadequate public toilets, but at the same time organize healthy organic vegetarian meals three times a day for ten days for well over a thousand people—and clean up afterwards.

On the first night, one clearly engaged viewer asked me if our programs would include any Syrian films, given the considerable number of Syrians involved in the camp. We did include one such film, a great one, but it was from 1997. We needed something more immediate in this context. The next day Sherry found online another fine film—Crude Living on Oil in Syria by the journalist/director Rozh Ahmad, twenty minutes in length, and experimentally relentless in its exploration of the despoliation of a village, a people, and a landscape, all at once. Overall, we found that the most resonant films in the programs were those which, broadly speaking, insistently confronted the issues of the freedom and the safety and the right to movement in strikingly diverse landscapes.

Among them:

—Refugee children in a Tunisian camp across the Algerian border in the 1961 I Am Eight Years Old (Poliakoff & Masson, from an idea suggested by Frantz Fanon and René Vautier)

—African migrants, all illegals, resisting the police, blocking traffic, in the streets of Paris in 2005 in Sylvain George’s Do Not Go Gentle Into the Night

—Our own 41 Shots from 2000,(reframed for the audience in the context of the current Black Lives Matter movement), our account of the NYPD murder of immigrant peddler Amadou Diallo, in the context of the racist broken windows policy, still in international favor today

—Zelimir Zilnik’s Inventory (1973), shot in a Munich tenement building where an all but endless number of the guest-worker inhabitants and their families descend the stairs one at a time to identify themselves

—Queen Mother Moore’s (great) Speech at Greenhaven Prison in 1973, in the wake of the Attica Rebellion two years earlier

—Aryan Kaganof’s Threnody for the Victims of Marikana, from 2014, on the police massacre of South African platinum miners.

Were we annoyed at times—by the delays and other issues we are not able to explore here? Repeatedly, since we are all too human. But we got over it. The immediacy of the live open-air event made its definite and yet indefinable contribution to the texture and the rapid unfolding of the No Border events. We were not, as the media phrase goes, embedded or even really encamped: we were both inside and outside at once, in the unfolding of the movement of movements, thanks to the activist audience, a temporary collective, during the open-air screenings.

- An international crew of graffiti writers (i.e., part-time outlaws) undertook to paint an ambitious mural on the massive front wall of the Law Building, with materials paid for by No Border. I watched them, absorbed by the seamlessly cooperative materialization of the pictorial drama, a bit ticked that so few among the several thousand circulating on the grounds of the campus allowed themselves to be drawn in, astonished by the result.

Ship of Fools/Ship of State/the EU rapidly sinking into the sea from the massive weight of its own contradictions, its borderline irrationality, creating its own tumult.

Another death ship.

I asked a graffiti writer/artist about the significance of the two small signs on the wall. They were a warning: don’t break the law against defacing public buildings with posters. The mural was a double affront against this Law.

A few days after No Border was over, the outlaw mural was painted over. The Law Building immediately regained its temporarily violated identity.

Resistance (tryptich/Sherry Millner)

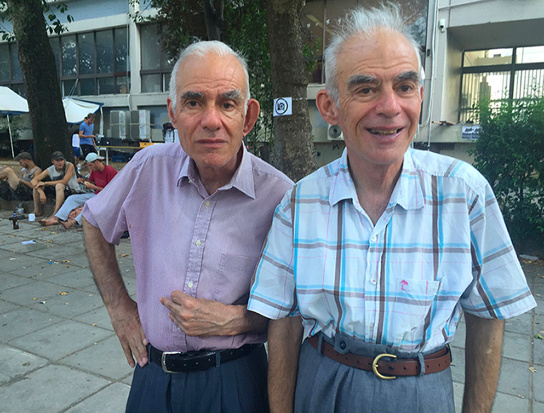

- On the campus of Aristotle University, just after a small boisterous demo of migrants passes us by, a demo inside the demo greeted with cheers, I ask a friend about a pair of older men whom I have seen several times circulating among the camp. They at once stand out amid the mostly youthful no-borderers and yet look completely at home. My friend says that they are well known. They never miss a demo and are regarded as underground local heroes. We decide to talk to them.

“You have to be constant to your beliefs, be loyal, stay with your comrades, stay with the party.” From this, I wonder if they mean the Greek Communist Party, which is regarded with considerable contempt here. But who knows? These guys appear to be anything but doctrinaire.

Local heroes, visiting the encampment

They mention that when they were children their village had been burned to the ground by the Nazis. In that sense they also had once, a long time ago, been refugees.

About the refugees: What did they do to suffer? Why should they suffer all this, kids and women, forced to leave their homes?

And on the US: Did you see what happened, with the police murdering blacks….?

The brothers are named Anestis and Michalis.

×

To be continued…