Images, notes, and quotes on and around the No Border encampment in Thessaloniki, July 2016 (rendered in the light of anarchist illegalism).

by Ernest Larsen

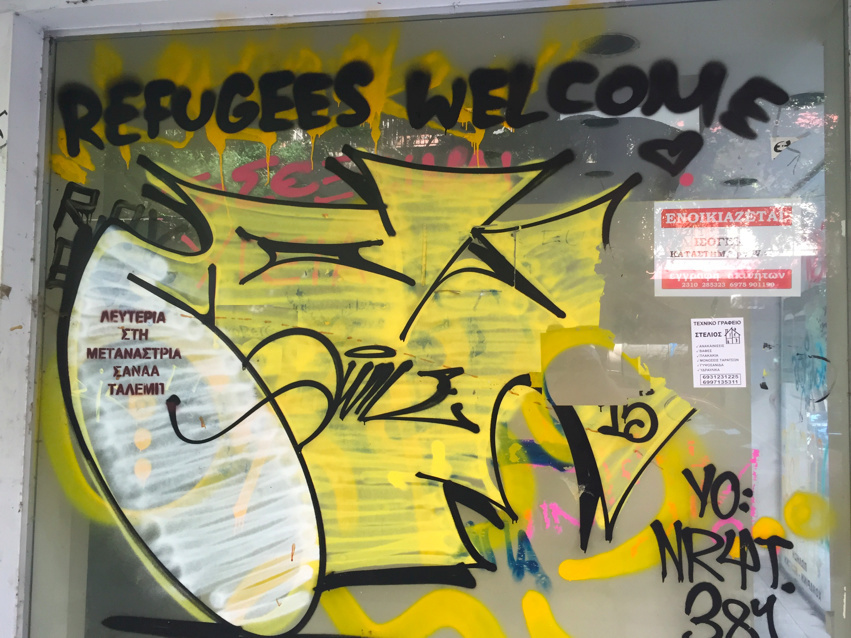

Graffiti on window of abandoned store in Thessaloniki, July 2016

“Flipping a Coin” is less an essay than a narrative construction, an indeterminate, deliberately ramshackle form, built up of quotes, long and short, a variety of digital images and photomontages, appropriated texts, anecdotes, personal history, reports, shards of literary, historical, and political analysis, interviews, memories, jokes, graffiti, more jokes. The perhaps unusually over-abundant images are not intended to provide the customary solace of illustration—they aspire to be as indispensable as the texts to the overall flow and meander of ideas and affects. “Flipping a Coin” is, let’s stipulate, less an essay than an occupation of the apparent space of an essay, inside and out—a squatted construction within an ancient literary institution. Mercifully, the literary police are not to be seen on the premises, nor lurking on the outskirts, in readiness to attack if given the go-ahead.

Beloved comrades in Thessaloniki have gently hinted that whatever value “Flipping a Coin” might have in clarifying our moment might be considerably advanced if I were to take the step (the radical step for someone like me who obstinately finds a profusion of disparate building materials to be not a stumbling block but a way forward), if I were to take the baby step of providing a guide or even a table of contents or at least a few bare hints of a structure to the document.

I take the No Border events in Thessaloniki in July 2016 as an opportunity to begin to understand an inescapable, untenable, radically unstable, irreconcilable contradiction: legality/illegality. Strangely and/or inevitably, it may well be that only anarchists and autonomists (and perhaps those who find themselves, like it or not, at least temporarily squatting in the zone of the anarchistic) are politically, experientially, and temperamentally equipped to grasp this elusive contradiction.

“Flipping a Coin” proposes to explore aspects of the histories and the current flowering of anarchist illegalism as comprehended within the compass of what is described therein as a politics of the excluded, by focusing on the No Border events in July 2016 in Thessaloniki, in militant support of migrant struggles.

It is also proposed that anarchism’s historically dynamic exploration of new and potential forms of existence can be best comprehended within the broad, unenclosed field of radical potentiality, within, that is, the role and efficacy of resistance culture—-on the principle that resistance culture is by definition borderless. Which is why whatever this is is squatted, deceptively but deliberately taking on the appearance of being in process.

Pin Prick (tryptich/Sherry Millner)

“Out of necessity, this war on terror has become borderless.”

Epigrammatic line uttered over a secure phone by an actor playing “Langley,” a CIA officer in the film Good Kill (2014), which is about the effects of drone warfare on stateside drone pilots, sitting at computer terminals in Nevada. The unseen Langley is distinctively voiced by Peter Coyote, who in his youth was a Digger (communing anarchists in San Francisco in the 1960s) and a founding member of the radical San Francisco Mime Troupe.

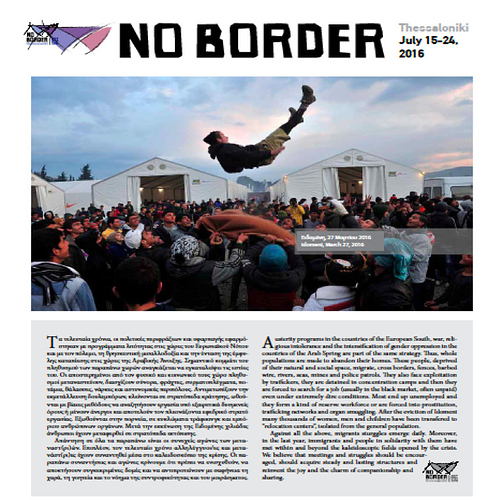

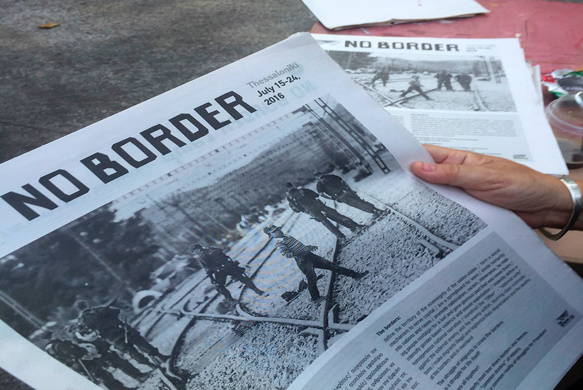

The two issues of No Border Thessaloniki, printed in three languages: Greek, Arabic, and English

Let us start after the fact, as in a film that begins with a flashback. Here then is the No Border Assembly’s account:

No Border 2016 in retrospect

On the 24th of July 2016 in Thessaloniki, Greece, a ten-day No Border Camp came to an end. It was one of the largest in the history of No Border Camps, and one of the most discussed in the bourgeois media. It also stands out for being followed by the most brutal and vengeful State repression.

The Thessaloniki No Border Camp had been attacked by the mass media even before it had started.

Two days after it had finished, a grand scale police operation targeted the social movement and specifically the structures of migrants’ self-organization. Three occupied migrants’ homes were evacuated. Indeed, it was made perfectly clear that practical solidarity and communities of struggle where locals and migrants fight together are most threatening for the authorities and the dominant order. If it had not been for this police operation, in this announcement we would be limiting ourselves to a description of the 50 workshops that were realized during the camp, of the networking meetings and discussions amongst people from Europe, North Africa, Turkey, of the demonstration at the detention centers in Paranesti and Xanthi, of the march against the Evros Fence.

Images of the No Border Camp soup kitchen, from the window of a workshop site

If it hadn’t been for the police operation, we would now be recounting the march of solidarity to migrants in the streets of Thessaloniki of several thousands of people, led by a bloc of 500 sans papiers.

We would be discussing the protests at the consulates of France and Germany, as well as the first international action of solidarity to the social movement in Turkey, a demonstration to the Turkish consulate against militarization and repression now spreading throughout Turkey under the pretext of the “response to the coup.” And we would add that there were organized and spontaneous meetings and discussions at the No Border Camp by people who were active across the “Balkan Route” during the last year in structures of practical and political solidarity on the islands, in the cities and at the borders of Greece and other Balkan countries. And we would underline the most essential feat of this No Border Camp, namely the deepening of relations between locals and migrants, and—most crucially—the realization of migrants’ autonomous assemblies and discussions—sans papiers living in the city, migrants living in Europe, refugees staying in the detention camps.

We had not realized how threatening these relations and these assemblies are for the powers that be. Now that we have, we are determined to confirm this threat by continuing our struggles. This, of course, is a matter of practical actions and of collective organizing. It is not a matter of words. However, this retrospective text consists of words only, so let us add a few more.

First, let us say a few words about the government’s total humbug about the detention camps around Thessaloniki, which it calls “organized structures,” while calling the squatted homes “caricatures of structures that create insecurity.” The minister Toskas spoke of “8,500 refugees being hosted by the State in acceptable conditions after they fled the disgusting situation in Idomeni, while these occupied places only hosted 32.” He lied. There are not only 8,500 “invisibles” in State custody. There are another 8,000 in Cherso and Polykastro (in the area of Kilkis), 1,500 in the area of Pieria (Iraklis and Petra Olympou), 1,340 in Yannitsa and Alexandria, as well as 750 in Kavala and Drama. At a short distance from Thessaloniki, 30 to 60 minutes in a car, there are 16,000 invisibles, crammed in industrial buildings or in camps in the middle of nowhere. If we expand the radius, the invisibles’ number reaches 20,000.

This is obviously a large number. And it is obviously much better for the State for this number to remain vague or secret and for these people to gradually become ghettoized, rather than for them to come into contact with the locals who are fighting against injustice, to join their struggles, or, worse still, to organize their own resistance. As we had expected, those of the migrants who had been transferred to the “hospitality centers” of “State solidarity” after their brutal evictions from the squats, immediately wanted to be taken away. Indeed, not one of the migrants could tolerate the “acceptable conditions” Toskas boasted about. Whoever had had even one day of experience at the evacuated squats, had found medical and legal aid there, had created relationships of equality with the locals and the Europeans, had joined their protests. Some moved on, others became integrated in the fabric of the city, some chose to participate in communities of struggle.

Perhaps the residents of this city do not know that after the evacuation, the police had exact orders as to the number of migrants it could arrest, so that Toskas could then be able to speak of “32 people.” The police had exact orders as to what kinds of people it would arrest, so they were careful not to touch families and children, because images of crying babies in police vans would then speak louder than the talking heads of State propaganda. The residents of this city did not see the gleeful smile on the faces of riot cops as they were denying entry to the evacuated Orfanotrofio squat to a person who wanted to bring out from the debris the medication for a diabetic migrant who had just been arrested. These reality snapshots might be buried under the tons of dust of the bulldozer, but all the dust and detritus in this city cannot cover up the brutality of the authorities.

Demolition of Orfanotrofio squat, Thessaloniki

…We happen to be living in the real world, and not in social media networks or ministries and shady dealing bureaus, so we know that the networks of drug smuggling that are now doing business at the university and the Rotunda square are also active in the State’s “hospitality centers” that the minister of Public Order is so proud of. In other words, solidarity groups cannot enter detention camps, but drug dealers can and should. Using drug smuggling for public space management (university campus, Rotunda square) or for population management (first in Idomeni at its final stage, i.e. before its eviction, now at the “hospitality centers”) is a well-worn method of governance: It destroys communities, it increases insecurity and it encourages violent behavior amongst the disenfranchised. It destroys any collective process, replaces social networks by mafias and authoritarian structures, and turns these detention centers into ghettos under the control of micro-gangs.

Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury to worry about the hurt feelings of Syriza members: They can hardly believe the shift of the Syriza government from the allegedly uncompromised anti-austerity, “anti-memorandum struggle” towards “State-managed charity for refugees” and now suddenly to the full monty “dogma of law and order.” Whatever these disappointed members feel, the government has chosen to continue the repressive policies of the right-wing Dendias period, in the broader context of both a material devaluation of life here due to a global capitalist attack, and a total moral devaluation of people through the official treatment of migrants as subhumans. All the government wants is to remain in government—and how able it is indeed to preserve social peace.

Left governmentality preserving social peace—this is where authoritarian left rhetoric meets the para-State mafia, the priesthood, the fascists, the snitches and collaborators. A bulldozer pulling down a haven of freedom is now the shameful emblem of their law and order. They had to resort to raw and brutal repression and to preposterous lies. This proves their weakness and embarrassment.

Demolition of Orfanotrofio squat, Thessaloniki

With the common struggles of locals and migrants for freedom and dignity we will make their worst fears and nightmares come true.

—No Border Assembly 2016

- Preamble: September 2009

In Europe, in motion, pre-ambling, prospectively enlivened by reports of anarchist struggle in Greece, we (Sherry and I) thought we might fly to Thessaloniki. I happened to email Iain Boal, who urged us, no doubt about it, to contact L. and N., anarchists who’d started the migrant support group Clandestina, who were involved in the Greek translation and publication of the Retort book Afflicted Powers. They’d once helped run a pirate radio station, were tirelessly brilliant organizers translators writers punk musicians graphic artists and and…We were in luck.

The insurrection of December ’08–January ’09 was easily the most incandescent revolt in Europe since ’68. We wanted, if possible, to feel the pulse of its aftermath.

We were animated not only by this revolt’s effusion of an anarchism rooted in several generations of Greek history, but maybe even more by its striking alignment of what came to be called a politics of the excluded—which seemed like a new, more complex way to think and act through alliance, solidarity, the courage of the (newer) social movements in the Greek cities.

Who were the excluded? Autonomous unions, the sans papiers, the ever-growing unarmed army of precarious workers, the unemployed and underemployed, the disaffected yet passionate youth living without observable reservations in the embrace of the present, anarchists, antiauthoritarians, and autonomists. Those that didn’t fit and probably never would. The temporarily or permanently unreconciled.

- A text from that period, announcing a new-er kind of social center, bringing together migrants, refugees, and anarchists:

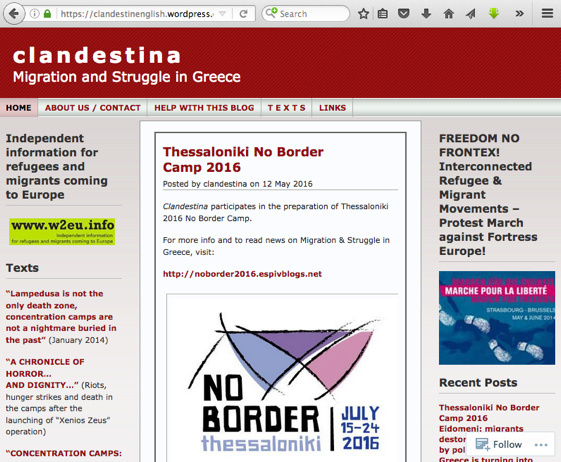

Clandestina: Migration and Struggle in Greece

O Dromos

…this is the summer of ‘09…Anti-immigrant terror gears up…a summer of racism, incarceration, death…struggle is the way!

we meet at O Dromos [The Streets]…

…for the independent struggle and organization of immigrants and refugees.

Immigrants and refugees, people from different places, we fight together. Greeks fight alongside immigrants, because the degradation of immigrants affects us all and intensifies exploitation in general.

Immigrants and refugees, individually or collectively, are by their very position a resistant force and find themselves targeted by the system. We should find ways to organize collectively and put solidarity into practice. Each person’s social position allows him/her to act in certain ways, but also charges him/her with the responsibility to seek points of contact with others—primarily with the newcomer refugees…

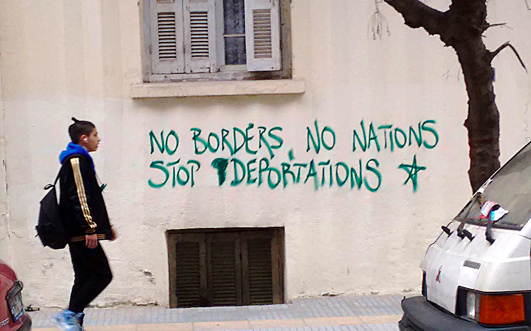

Graffiti, Thessaloniki, summer 2016

Fortress Europe is the future of us all, unless we fight against it together. If neoliberalism (rampant exploitation without any protection) is the form that Capital takes today, Fortress Europe and what we call Dungeon Europe is the form the State assumes. In this framework, society itself is becoming more racist and fascist. We must fight against the conditions that separate and downgrade 1/10 of the population of the country and condemn refugees to conditions of slavery. If these conditions become their fate, resistance will become increasingly harder for everyone…we may be very different from one another, but coming together is the first step towards overcoming our differences, and unity in struggle is the only way to build solidarity.

How are such groups and individuals positioned to resist?

Let’s say that they/she/he are caught among a narrow range of (im)possibilities. Since they are obliged/forced to move while being legally prevented from moving, they are obliged to define (re-define) themselves through illegal movement.

Once positioned as illegal, as moving, choosing to move, or forced to move beyond the law, then no matter what happens later, no matter what accommodations may or may not be made or achieved or even accepted down the line, however reluctantly (assuming that negative, for the moment), then a migrant always remains aware deep down of a basic fact: either one lives in the Fortress and experiences the comforting illusion of being protected by it, or one is the prey of the state and with that recognition must therefore turn against it, make a stand. As if to survive while being illegal is to be closer to a state of nature, in solidarity with it, forced into the undignified position of runaway domestic animals hidden among the grasslands, prepared to strike, if necessary, remembering even or especially in the defensive act of retaliation that they are still somehow not really tamed. As if to resist is to acknowledge that one has become or always has been untamed. Since resistance dams/damns the inhibitions, even when it loses it wins.

This unpredictable resource becomes one root advantage of the excluded, then, and links them directly to all the excluded. And this is one reason why the broad alliance of the excluded is speedily perceived (from the other side of the fence/border) as dangerous. Having learned how to break the rules, they will not be deterred by them.

By the Light of the Moon (In Idomeni) (tryptich/Sherry Millner)

- No Border Camps

From the Wikipedia page “No Border network”:

Groups from the No Border network have been involved in organising a number of protest camps (called “No Border Camps” or sometimes “Border Camps”), e.g. in Strasbourg, France (2002), Frassanito, Italy (2003), Cologne (2003, 2012); Xanthi, Greece (2005), Gatwick Airport (2007), Ukraine (near Uzhgorod), also 2007, United Kingdom; at Patras, Greece; Dikili, Turkey (2008); Calais, France (2009, 2015); Lesvos, Greece (2009); Brussels, Belgium (2010); Siva Reka, Bulgaria (2011); Stockholm, Sweden (2012); Rotterdam, the Netherlands (2013); Ventimiglia, Italy (2015), [and this year 2016, in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece]…

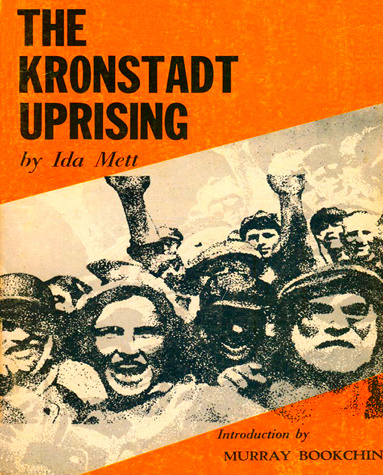

In February 2010 No Border groups from the UK and France opened a large centre for refugees sleeping rough in Calais, France, under the name “Kronstadt Hangar”…

A note on the first Kronstadt Hangar, from the Kronstadt Izvestia of 1921:

"The sailors rejoiced that power had passed into the hands of the laboring people. The Communists vainly attempted to provoke us, saying that we did not have the right to revolt against Communist Soviet power. The sailors, in revolutionary ecstasy, replied to this that death was better than the Communist yoke, and with the cry, ‘Long live the Kronstadt sailors, soldiers and workers,’ went to the hangar where the seaplanes were located.

“In the hangar we gathered for a second time. Comrade Balabanov instructed that all seamen should be armed, but several, afraid of spilling blood, did not agree with this order, and as we will see below, paid cruelly for their love of peace and their trusting natures.”

…Calais authorities have accused “extremist activists” within the No Borders network of being “driven by an anarchist ideology of hatred of all laws and frontiers” and engaging in, and encouraging, violence and harassment against French police and social workers at the Calais Jungle migrant camp, as well as “manipulating” and “misleading” the migrants living there.

This amusingly hyperventilated accusation, itself so extremist, might possibly be grounded in a twisted fragment of truth. If we strip it of its excess, strain it well, rinse three times, spin-dry, what remains? A sharpened problematic that the twenty-first-century reemergence and international resurgence of anarchism (and antiauthoritarian and autonomist movements) has posed once again, but as if for the first time—even though it’s been at the heart of anarchism since the late nineteenth century: the question or the articulation of the relationship between the (massive centuries-old edifice of the Western-bourgeois-capitalist) legal order and the border, which became fully operative due to the realignment of national interests in the wake of World War I.

Order/Border.

“Papers, please.”

So this is not a brand-new question. Nevertheless, historically speaking, it is perhaps most forcefully explicated and memorably captured, not in a political essay, but in a novel. B. Traven’s 1926 novel The Death Ship is built upon this question, at the crucial point of the post-World War I emergence of newly disciplinary nationalism, signified and enforced by the use of the passport, of verifiable identity constituted as citizenship. “In any civilized country, he who has no passport is nobody.” The premise of the highly conceptual plot is that its sailor protagonist has lost all his papers.

Consider this dialogue between an official and the novel’s able-bodied seaman hero:

“The state cannot make use of human beings. It would cease to exist. Human beings

only make trouble. Men cut out of cardboard do not make trouble.”

“It looks, sir, as if you would doubt the fact that I was born at all.”

“Right, my man. Think it silly or not. I doubt your birth as long as you have no certificate of your birth.”

“I am not to blame. It is the system of which I am the slave.”

“Nationality?”

“What a question! It has been testified to by my consuls that I no longer have such a

thing as a nationality, since there is not the slightest proof that I was born.”

In the end the hero must sign on to a death ship—a vessel planned by its corporate owners to be scuttled at sea in order to collect on a fraudulent and exorbitant insurance claim.

(The sea, as such, becomes little more than a bottomless abyss adjacent to the nation-state. A graveyard—as is the Mediterranean today.)

I have written elsewhere that Traven, himself for some years an anarchist refugee on the run, “attempts to re-ground or foreground the hypothetical aspect of fiction, fiction as a production of knowledge about the latent, underexplored, or insufficiently imagined potentialities of existence.”

In that sense, much if not all consciously political fiction could be said to be about migration, about the great or even insuperable difficulty of getting somewhere you want to go, about the paradigm of the refugee—though in discussing The Death Ship I was making that point specifically about an anarchist fiction, which, I believe, reliably gathers its best energies from situations of extremity. Unless one makes such a case explicitly, then culture—the production, that is, of radical culture—always appears as something extra, a surplus or supplement, nice enough to while away one’s free time, if one is free and has time, but not really necessary, something to do or think about after the real work is done. It (radical culture) is in a sense then regularly excluded in advance (as a production of knowledge).

The ambitious cultural program of No Border Thessaloniki included theater, music, art, film, graffiti. Very often real politics (usually, an assembly) delayed whatever cultural event was on the schedule. Sensible and even desirable—and apparently unquestioned—it was more or less an automatic response. It might have been salutary to explore the issue. After all, experimental thinking is also a practice—and takes some practice. The adventure of politics requires experience in experimental thinking. Culture is probably the most appropriate and compelling ground on which experimental thinking can be practiced. It might even be dangerous for the excluded to exclude it without due consideration.

×

To be continued…