At the website Runway, which focuses on experimental art in Australia, Macushla Robinson writes about the “invisible dark matter” of labor performed by women in the art world. She notes that, as theorists like Silvia Federici have shown, much labor performed by women (such as child care) is integral to the functioning of the capitalist system yet goes largely unpaid. Robinson observes the same dynamics within the art world, but to a more extreme degree, where “the free labour and rampant exploitation” of women “is, by its very nature, undocumented.” Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

The role of muse is something to which many have aspired. Yet like any other fairytale, it is more glamorous in the story than in real life and has typically left women without any agency in the act of creation. In the Romantic tradition, ‘[T]he sublime is specifically a male achievement gained through women as female objects or through female Nature, and so is closed off to women’. Women’s perceived closeness to nature, then, means that they cannot be artists, but only represented by artists.

Women’s perceived proximity to nature has been instrumental in their oppression. The capitalist system has appropriated womens’ labour to support the exploitation of a male waged workforce, including in the romanticised cultural sector. As women have been culturally constructed as closer to nature, and biologically more capable of love than men, their ‘labours of love’ have often been framed as a natural resource. Despite the efforts of many feminists to invert the hierarchy of values that maligns both women and nature, women remain sidelined by this logic.

Women in the culture sector, who genuinely love and believe in their work, often work for free. In fact, perhaps because of the privileged place of love in relation to art and the romanticism of the gendered structure of creator and muse, this undervaluing of women’s work is more extreme than in many other aspects of Western society.

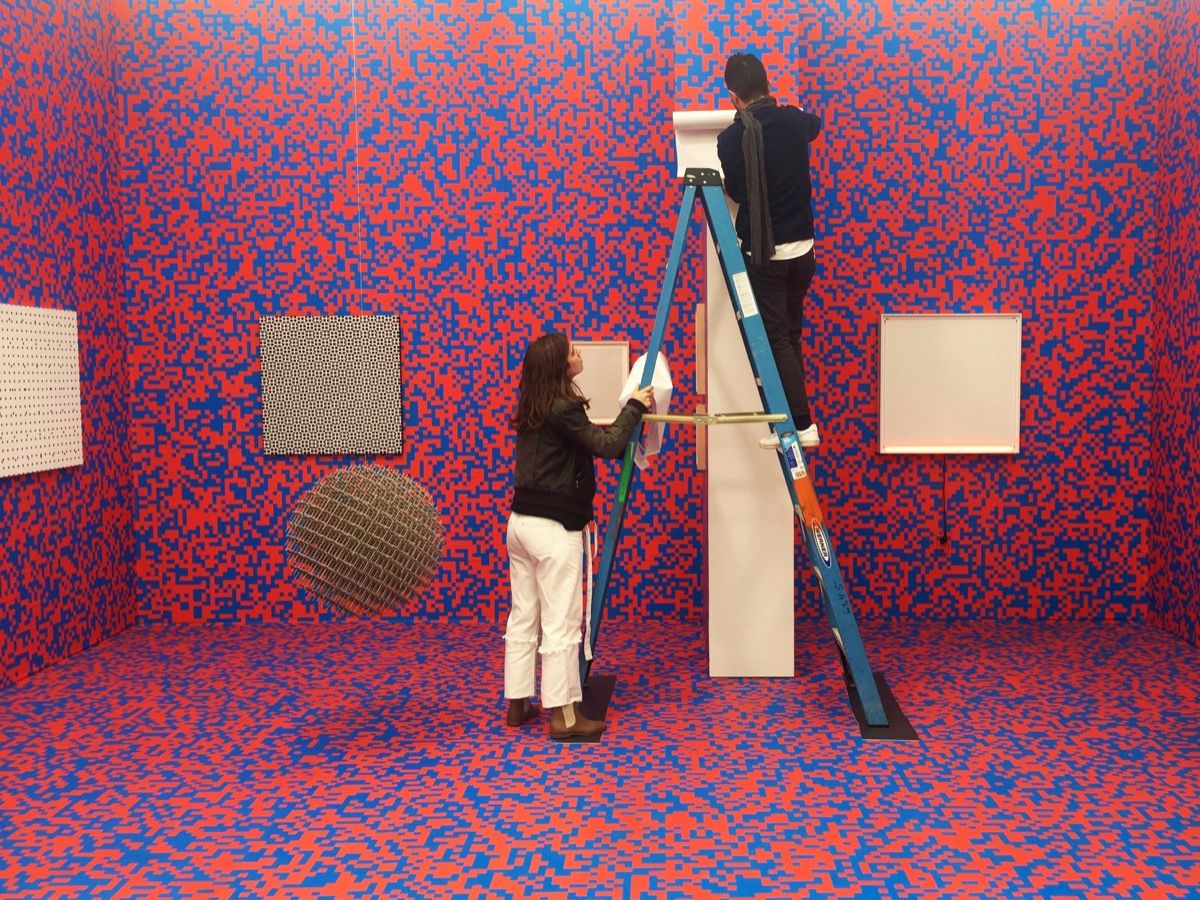

Image by Irina Arellano-Weiss. Originally published in Art Handler magazine, issue 2, Nov. 2016.