In The Guardian, novelist Andrew O’Hagan ponders how the ongoing elimination of privacy by ubiquitous and invasive social media will affect the novel. An art form premised on solitude and sustained focus, the novel seems ill-suited to our era of compulsive sociability and short attention spans. But as O’Hagan writes, the novel will likely endure, albeit in a changed form: “Maybe the abolition of privacy will kill the novel. But more likely, as with the invention of trains or rockets or sex, it will make it new.” Here’s an excerpt from the essay:

The other day I taped over the camera on my computer. Then I went upstairs and disabled the data collection capability on the TV. Because of several stories of mine, I’d suffered a few cyber-attacks recently, and, though a paragon of dullness, I decided to greet the future by making it harder to find me. One of the great fights of the 21st century will be the fight for privacy and self-ownership, which is also, to my mind, the struggle for literature as distinct from the dark babble of social media. Writers thrive on privacy, not on Twitter, and so do readers when the lights are low. Giving your sentences thoughtlessly away, and for nothing, seems a small death to contemplation, and does harm to the profession of writing, where you’re paid because you’re good at it. We are all entertainers now, politicians are theatrical in their every move, but even merely passable writers have something large at stake when it comes to opposing the global stupidity contest. Literature, which includes great journalism, might enhance the public sphere but it more precisely enriches the private one, and we are now at the point where privacy, the whole secret history of a people, might be the only corrective we have to the political forces embezzling our times…

In 2010 Mark Zuckerberg told a conference in San Francisco that privacy is no longer a social norm, and Nick Denton of Gawker spoke for a whole generation when he said that “every infringement of privacy is sort of liberating”. For any writer, that’s a call to action. When you write fiction you’re in a constant state of production, and I don’t mean you’re always writing. I mean you point yourself in the direction of the narratives you know you can write. I’m always going out of the house to find stories and always being changed by them. There is no gold medal for that, it’s just a habit some people have, but it seems reasonable to believe that such work sets up conversations that novelists might not otherwise have. When I’m reporting nowadays I feel less like a news gatherer and more like an actuality seeker, someone for whom the techniques of fiction are never foreign and seldom inappropriate. In recent years, I’ve tended to write about people who inhabit a reality they made for themselves or that in other ways consorts with fiction, and I was required to enter their ether and dance with their shades in order to find the story. When I was a young reader, I learned from the poets not to trust reality – “reality is a cliche from which we escape by metaphor,” Wallace Stevens wrote – and the internet figures I got involved with for The Secret Life: Three True Stories depend for their existence and their power in the world on a high degree of artificiality.

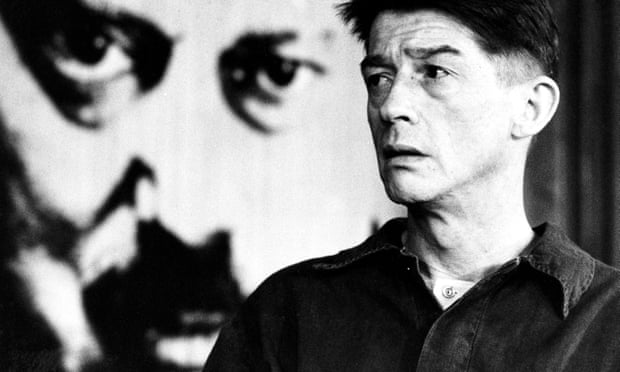

Image: John Hurt as Winston Smith in the film of version of Orwell’s 1984. Via The Guardian.