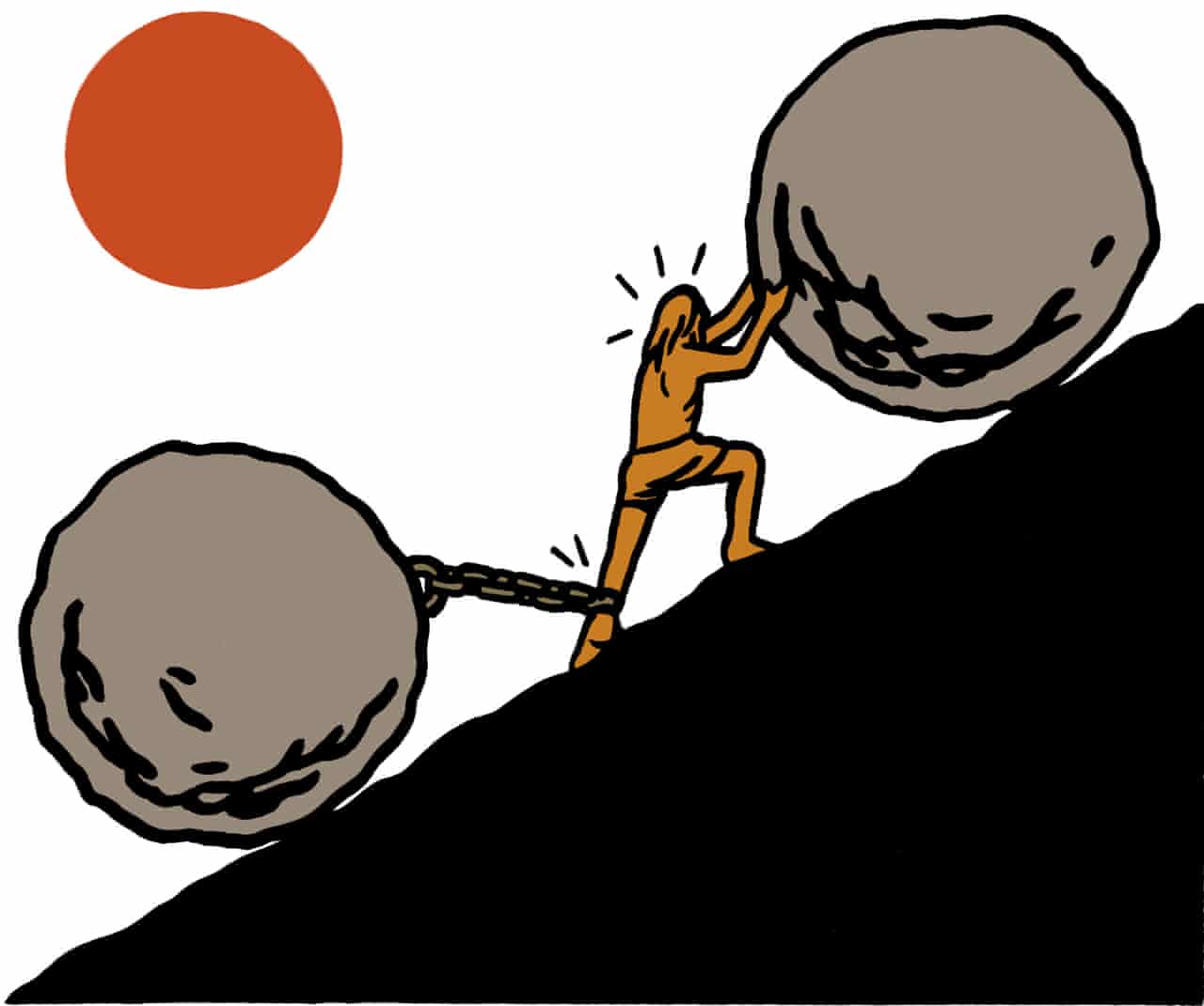

In The Guardian, Oliver Burkeman surveys the history and empty promises of the time-management industry. Developed in the early twentieth-century to maximize the efficiency—that is, the exploitation—of manual laborers in factories, the philosophy of time management is more popular and profitable than even today, when precarious work and information technology has dissolved the border between work and nonwork. But as Burkeman writes, any time gained by increased efficiency is almost always filled by more work, not more freedom. Check out an excerpt from the long read below, or find the full piece here.

Above all, time management promises that a meaningful life might still be possible in this profit-driven environment, as Melissa Gregg explains in Counterproductive, a forthcoming history of the field. With the right techniques, the prophets of time management all implied, you could fashion a fulfilling life while simultaneously attending to the ever-increasing demands of your employer. This promise “comes back and back, in force, whenever there’s an economic downturn”, Gregg told me.

Especially at the higher-paid end of the employment spectrum, time management whispers of the possibility of something even more desirable: true peace of mind. “It is possible for a person to have an overwhelming number of things to do and still function productively with a clear head and a positive sense of relaxed control,” the contemporary king of the productivity gurus, David Allen, declared in his 2001 bestseller, Getting Things Done. “You can experience what the martial artists call a ‘mind like water’, and top athletes refer to as ‘the zone’.”

As Gregg points out, it is significant that “personal productivity” puts the burden of reconciling these demands squarely on our shoulders as individuals. Time management gurus rarely stop to ask whether the task of merely staying afloat in the modern economy – holding down a job, paying the mortgage, being a good-enough parent – really ought to require rendering ourselves inhumanly efficient in the first place.

Image via The Guardian.