In the Boston Review, philosopher Philip Kitcher reviews Why Trust Science? by the distinguished historian of science Naomi Oreske. It is a timely book, as public debate today is rife with politically motivated skepticism about the authority of science when it comes to climate change, vaccinations against disease, genetically modified food, and more. As Kitcher writes, the strength of Why Trust Science? is that it bases the “objectivity” of science not on some abstract and universal method, but on its deeply social nature. Check out an excerpt from the review below.

Two features of science, she claims, account for its trustworthiness: its “sustained engagement with the world” together with “its social character.” Her emphasis on the second feature may surprise readers used to thinking of science as a tidy epistemic enterprise neatly insulated from social influence, but this view emerges clearly from her sober review of studies of science by historians, philosophers, sociologists, and anthropologists during the past half century.

She reviews that history in her first chapter. The narrative she presents moves firmly away from the quest to identify a particular “method” that makes science trustworthy, toward an emphasis on the distinctive “collective” dimension of science. Before the 1950s, logical empiricist philosophers—taking up the “dream of positive knowledge,” as Oreskes calls it, that originated with the French sociologist August Comte in the nineteenth century—tried to articulate a precise account of scientific method, emphasizing the importance of testing scientific theories against empirical observations. Historical studies of scientific practice, including early writings by the microbiologist Ludwig Fleck and the physicist Pierre Duhem as well as later work by the historically oriented thinkers Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend, revealed the inadequacy of those attempts. Feyerabend’s most famous book, in fact, is called Against Method (1975).

Those studies, in turn, paved the way for a sociology of scientific knowledge, whose initial thrust—in the work of what came to be known as the Edinburgh school, by Barry Barnes, David Bloor, and Steven Shapin—was often read as suggesting that the beliefs advanced by scientists were no more credible than those maintained by anyone else. Eventually, however, more subtle proposals emerged, fueled by feminist scholars such as Helen Longino. They restored the objectivity of science, Oreskes writes, by viewing it as a collective achievement. She praises feminist work on science, in particular, for showing that the objectivity of scientific research depends on critical debate and exchange within a diverse community of investigators. As she puts it, “diversity does not heal all epistemic ills, but ceteris paribus a diverse community that embraces criticism is more likely to detect and correct error than a homogenous and self-satisfied one.”

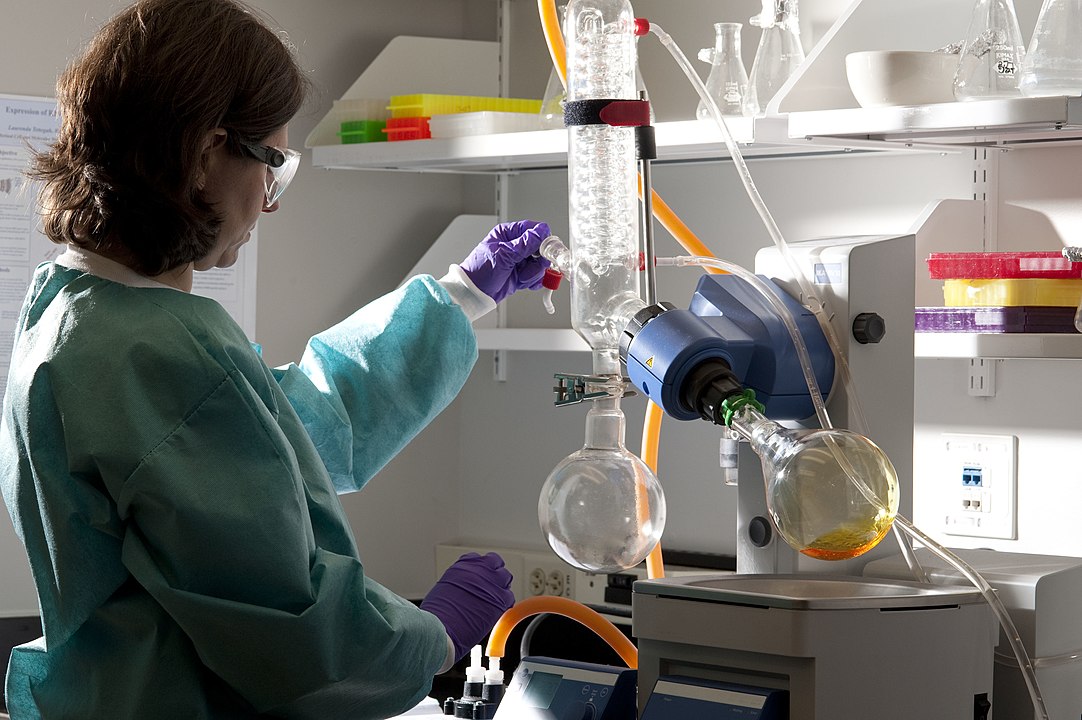

Image by National Eye Institute - Laboratory Experiment. CC BY 2.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.