The Boston Review has an excerpt from a new book by philosopher Jason Stanley entitled How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. In the excerpt, Stanley examines one of the most influential conceptions of free speech in the Anglophone world—that of John Stuart Mill, who argued emphatically for open and unfettered democratic discussion in On Liberty. Stanley suggests that this conception of free speech makes certain assumptions about the participants in the discussion, e.g., that they all strive to speak truthfully and persuade through facts rather than strong emotions. When these conditions don’t obtain—as in our current era of degraded political discourse—we must rethink our understanding of free speech, suggests Stanley, if we want to protect the very democratic norms it is designed to uphold. Here’s an excerpt:

Perhaps philosophy’s most famous defense of the freedom of speech was articulated by John Stuart Mill, who defended the ideal in his 1859 work, On Liberty. In chapter 2, “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” Mill argues that silencing any opinion is wrong, even if the opinion is false, because knowledge arises only from the “collision [of truth] with error.” In other words, true belief becomes knowledge only by emerging victorious from the din of argument and discussion, which must occur either with actual opponents or through internal dialogue. Without this process, even true belief remains mere “prejudice.” We must allow all speech, even defense of false claims and conspiracy theories, because it is only then that we have a chance of achieving knowledge.

Rightly or wrongly, many associate Mill’s On Liberty with the motif of a “marketplace of ideas,” a realm that, if left to operate on its own, will drive out prejudice and falsehood and produce knowledge. But this notion, like that of a free market generally, is predicated on a utopian conception of consumers. In the case of the metaphor of the marketplace of ideas, the utopian assumption is that conversation works by exchange of reasons: one party offers its reasons, which are then countered by the reasons of an opponent, until the truth ultimately emerges.

But conversation is not just used to communicate information. It is also used to shut out perspectives, raise fears, and heighten prejudice.

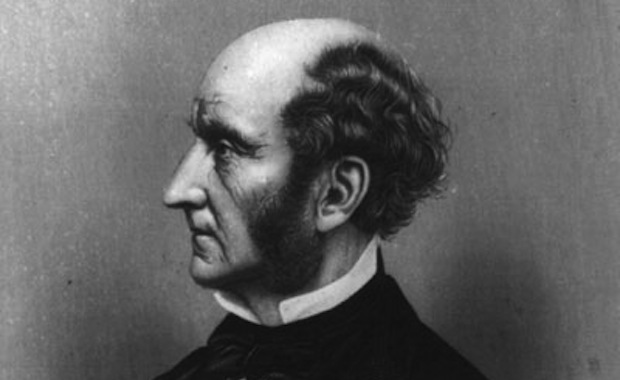

Image of John Stuart Mill via the Yale Books Blog.