In the November issue of e-flux journal, David Riff traces the motif of dancing throughout Marx’s work, from his youthful poetry to his groundbreaking text “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.” Here’s an excerpt from Riff’s piece:

There are traces of dancing in Marx’s texts, and, far from coincidental, they gel with the overall nexus of aesthetics, politics, and social dynamics in his writing. But do these traces add up? More simply put, is there any actual choreography to be found in Marx’s work? Is there any criticism of the wrong kinds of dances? Or any instruction on how to dance properly? If there is any place we should look for such a choreographic subcurrent, it is in Marx’s writing on the Revolution of 1848 and its aftermath. Again, bourgeois historiography gives us a trivial reason: according to Love and Capital, a recent biography focusing on the relationship between Jenny von Westphalen and her husband, Jenny and Marx danced their way in 1848 at a Worker’s Union Ball in Brussels, where, according to Mary Gabriel, the democratic dance floor no longer had a cordon between commoners and aristocrats, and Marx, surprisingly agile, turned and twisted his way through highly coordinated partner dances and quadrilles. So Marx danced, after all, with his ballroom baroness, on the eve of what was arguably the first failed proletarian revolution.

Marx’s reflections upon the dramaturgy of this failure would produce one of his famous and most literary texts, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (1852), a profoundly performative essay on how 1848 prompted Louis Bonaparte to take power and install himself as Napoleon the Third. Marx pays great attention to how politics is acted out as a spectacle, how revolutions are performed as plays and thus accessible to a form of historical-dramatic criticism. Their history repeats itself, first as tragedy then as farce. The champions of commerce may be a sorry lot, yet they don heroic costumes taken from Ancient Greece or Imperial Rome, learning lines that remain alien until they are perfectly naturalized and the actor finally becomes his role, turning into a mad Englishman who mines gold in Ethiopia for the Egyptian pharaohs. The bourgeois revolution is a delusional historical theater, where grand epic expositions quickly turn into operettas, quickly ending in a Katzenjammer and a hailstorm of rotten vegetables. Bourgeois revolution draws its rhetorical formulas and demands from the past, while the proletarian revolution of Marx’s nineteenth-century modernity has to take its poetry from the future. And here, we could add, completing the conjecture, this poetry of the future is not theater but dance.

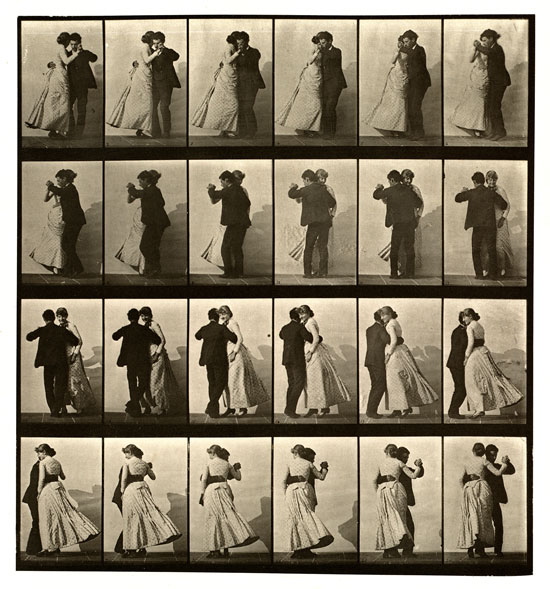

Image: Plate 197 from Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion (1887) shows two models dancing the waltz. Via e-flux journal.