Randy Kennedy writes a profile on the delightfully outspoken artist and architect Vito Acconci, who is the subject of an upcoming retrospective at MoMA PS1. Kennedy writes about Acconci’s transition from poet to artist to architect as well as his major performance pieces. The description of his infamous “Seedbed” (1972) was particularly interesting. Whereas I thought the piece was a comment on private/public space, it really sprang from Acconci’s interest in etymology. Kennedy writes, “The idea for the act under the floor arose linguistically, after he turned to a thesaurus to find synonyms for the word “foundation” and was struck by the poetry of “seedbed.” And in constructing the floor, he was already beginning to explore his interests in architecture and public space, in this case a space in which he could merge with the building, ceasing to be a discrete human presence and becoming instead a kind of quantum field.”

See the profile in partial below, or the full version via New York Times.

“I hated the word artist,” he said. “To me, even in the years when I was showing things in galleries, it seemed to me that I didn’t really have anything to do with art. The word itself sounded, and still sounds to me, like ‘high art,’ and that was never what I saw myself doing.”

As far as the art world was concerned, his leap into architecture — designs for things like public parks, airport rest areas and a man-made island — was almost as if Mr. Acconci decided to enter the witness protection program. But he disappeared right in the art world’s midst, continuing to teach generations of art students (at Brooklyn College and at Pratt Institute); working in a cluttered, book-saturated studio in Dumbo, Brooklyn; and lecturing so often over the years that his shambling-eccentric presence — his long unruly hair, his all-black wardrobe, his gravel-bed voice with its distinctive loping stutter and, before he quit, the endless cigarettes he would light and stub out and light again — became a kind of ongoing work in itself.

Born in the Bronx into a Catholic Italian family, the overprotected only son of a bathrobe manufacturer and a mother who later worked in a public-school cafeteria, Mr. Acconci came of age in the politically agitated years when artists began trying to find ways around the making and selling of objects. They turned to their bodies, their ideas and their actions as the currency of a new realm. Along with peers like Chris Burden, Adrian Piper, Dan Graham and Valie Export, Mr. Acconci began conceiving and documenting performances — at a rate of sometimes one a day in what he called “a kind of fever” in 1969 — that were conducted on the streets or for audiences so small that they seemed almost not to have happened.

In Mr. Acconci’s case, the work grew out of an experience as an aspiring poet and fiction writer whose fascination with the physical space of the page eventually led out into the world. In 1962, in thrall to postmodern writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet and John Hawkes, he enrolled in the graduate writing program at the University of Iowa, taking along with him a short story he had written, titled “Run-Around,” that when read anonymously in the class provoked a minor riot. Its subject, a horrifying surrealist-sculptural vision, was a recently limbless man. It began: “They cut him up and since the chairs had just been varnished for the celebration, he was set down on a giant floor urn. The chalice-shaped jar was waist-high for most people, but not for Rockram, because he had no legs.”

…

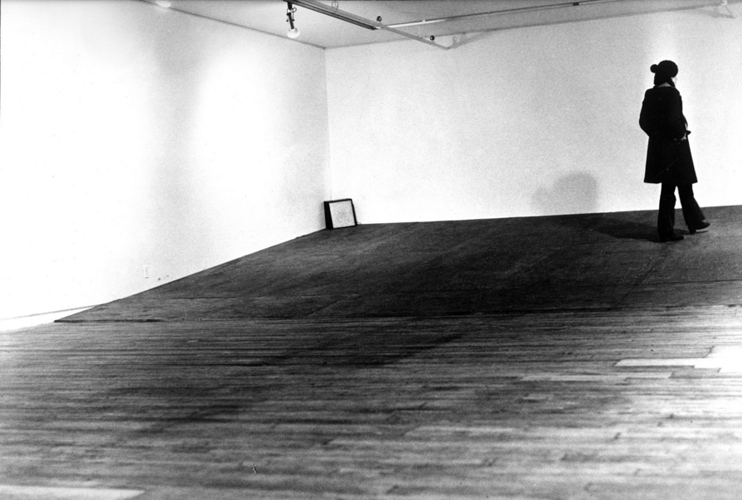

In “Seedbed,” (1972) — undoubtedly Mr. Acconci’s best-known piece, which has in a sense unfairly overshadowed much of his other work — he constructed an angled false floor at the Sonnebend Gallery in SoHo and hid himself beneath it with a microphone, speaking luridly to the people who walked above him, masturbating as he spoke. The piece became a touchstone of performance art in part because of its sheer, outlandish audacity. But it also drew a remarkable line through the preoccupations that began Mr. Acconci’s career and carry it up to the present day. The idea for the act under the floor arose linguistically, after he turned to a thesaurus to find synonyms for the word “foundation” and was struck by the poetry of “seedbed.” And in constructing the floor, he was already beginning to explore his interests in architecture and public space, in this case a space in which he could merge with the building, ceasing to be a discrete human presence and becoming instead a kind of quantum field.

“I wanted people to go through space somehow, not to have people in front of space, looking at something, bowing down to something,” Mr. Acconci said of the performance. “I wanted space people could be involved in.”

Holly Block, the executive director of the Bronx Museum, which commissioned an architectural environment from him in 2009, said: “A lot of people don’t understand Vito’s turn to architecture, but I think he wanted to be more ambitious and make pieces that lived in the world — and in people’s lives — in a different way than artworks usually do, and it was a risky and courageous thing to do.”

*Image from the film “Seedbed,” by Vito Acconci, from 1972. Credit Acconci Studio, New York, and the Museum of Modern Art