At Public Books, sociologist Maurizio Meloni explains the far-reaching social implications of the scientific field of epigenetics, which has been experiencing a revival in recent years. Epigenetics studies the traits of living creatures (including humans) passed from generation to generation that are not derived from DNA. In essence, it explores the “plasticity” of biological evolution, challenging the notion that the development of an organism is entirely influenced by DNA rather than its environment—by “nature” instead of “nurture.” Meloni argues that this challenge has major implications for how we understand human ethics and social behavior, as in this excerpt:

This shift is much more than just a biological one, however. Epigenetics and programs in Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) are contributing to the rewriting of the human body as permeable down to its genomic core, leaving it, therefore, vulnerable to new risks and new forms of intervention. As the first social analyses of epigenetics argue, what is at stake are the ways in which we understand the management of bodies and the reproduction of social norms.

How will such ideas—that, say, a future parent’s diet or lifestyle impacts their offspring’s well-being—change notions of responsibility and risk or normality and pathology? If cheap saliva testing can offer epigenetic markers to distinguish between chronological and biological age, who is going to use this knowledge and to what ends? At the level of population, social management questions with deep political implications are also being asked: What about groups exposed to famine or violence? Are they “damaged forever before birth,” as one sensationalist headline claimed when reporting on a pioneering study on epigenetic differences between the richest and poorest areas of Glasgow? If so, do they need some special form of help, or might their acquired harm make them unresponsive to future intervention?

These questions, though speculative, highlight the potential of epigenetic debates to challenge some established coordinates in 20th-century biology/society debates: namely, that there is a clear distinction between biological and social causes, genetic and environmental factors.

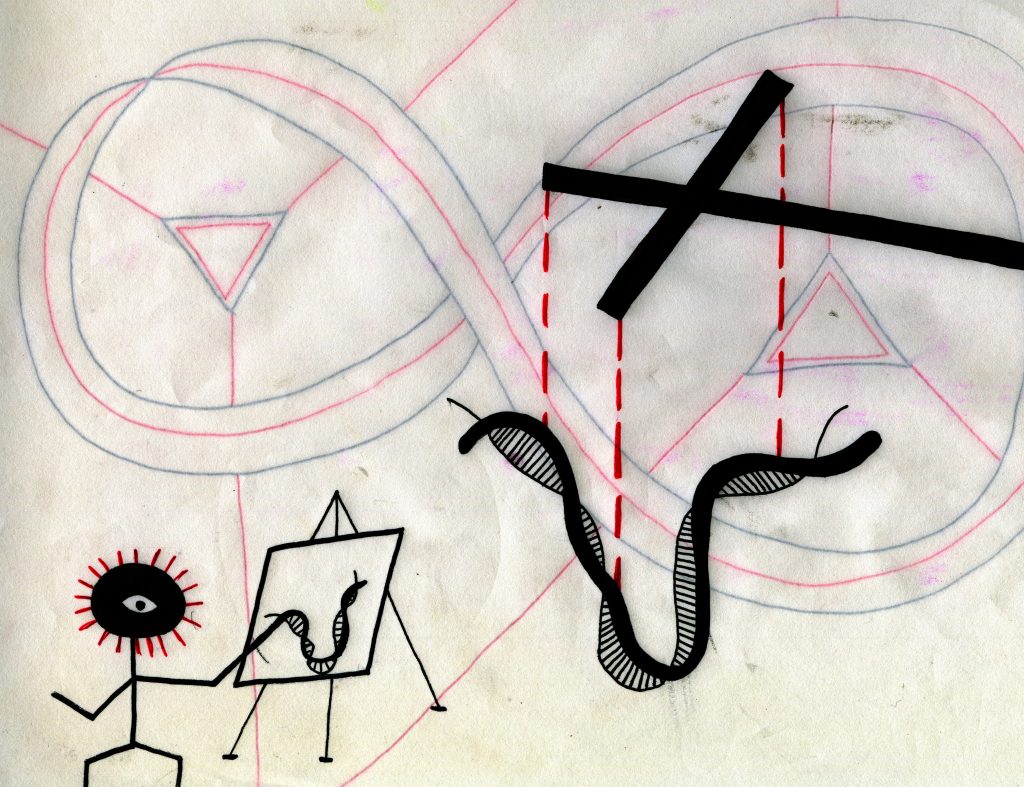

Image via Public Books.