In the Los Angeles Review of Books, philosopher Brad Evans interviews fellow philosopher Lewis R. Gordon, author of several books including What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to his Life and Thought (2015) and Existentia Africana: Understanding Africana Existential Thought (2000). Gordon discusses the enduring influence of Fanon on his work, decolonization as an open-ended process, and the beautiful non-utility of art. “Art brings value to our existence in a world,” states Gordon, “through the radicality of our non-necessity.” Check out an excerpt from the interview below.

BRAD EVANS: You have described art as being “the expression of human beings creating belonging in a world that really didn’t have to have us.” This understanding of art, which stands in marked contrast to art as the production of commodity fetishization, has a profound bearing on its relevance to the human condition, especially its violence. Given the definition you offer, what do you understand to be the relationship between art and violence?

LEWIS R. GORDON: I reject the model of art as the production of commodity fetishization. It is not that art can never be commodified or made into a fetish. My objection is that the story of art is only presented to us under specific social conditions. Euro-modern society and its celebration of capital are only parts of the human story. It is decadent to reduce art to a single element of what we sometimes do with it — namely, art for consumption.

Such an account of art is also a form of European arrogance wherein nothing exists except through actions of Europeans or whites. Ancient humanity decorated, found ways to season their food, made music, and dance. Some did so ritualistically; others did so for instrumental reasons long lost to the rest of us; and others did so simply for enjoyment, fun, or pleasure. Europe certainly didn’t invent the idea of a “good life.”

Yet the underlying question is: Why do so at all? Even if we enjoy doing something, we do sometimes have to be coaxed into that activity. I regard our species, and perhaps some of our related but now extinct cousins, as endowed with an extraordinary sense of awareness and critical possibilities that haunt each moment of lived investments. The fact that we puzzle over what preceded us and what will succeed us brings forth the existential conundrum of what we bring to reality as necessary despite our existence being contingent. For some, that occasions fear and trembling. For others, wonder. And, yes, there are those who are too busy to care. Yet even the last find pause for moments amid the ebb and flow of life in the range of aesthetic experience we have with objects and performances we call “art.” Art brings value to our existence in a world through the radicality of our non-necessity. In other words, because we are irrelevant to reality, it means our value, through art, must be on our terms. Art enables us to live despite the reality and infinite possibilities of the absurd — including the absurd notion that our existence is necessary.

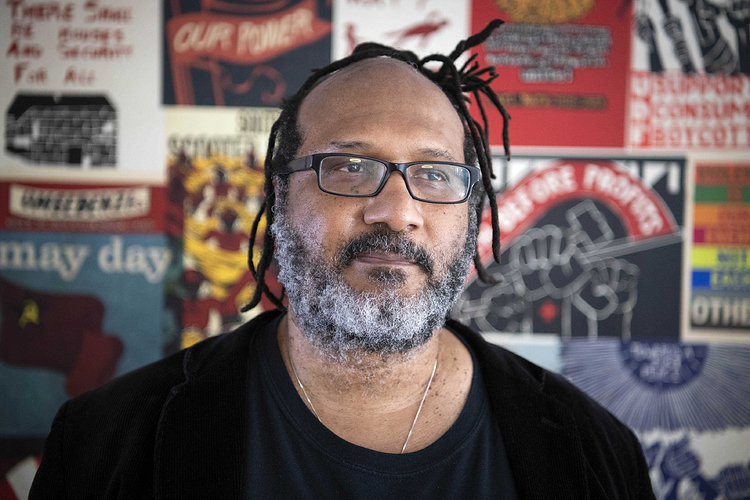

Image of Lewis R. Gordon via New Frame.