This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love, an incredibly eventful and vibrant few months of politics, culture, and pleasure centered on San Francisco in 1967. In The Nation, Ira Chernus writes about how the Summer of Love, which is often portrayed as an apolitical drug-fest, can actually provide lessons for subverting today’s governmental obsession with “national security.” He begins by noting that the DeYoung Museum—located in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, the epicenter of the Summer of Love—currently has an extensive exhibition devoted to that pivotal summer. Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

If you tour the exhibit, you might come away thinking that the political concerns of the time were no more than parenthetical bookends to that summer’s real action, its psychedelic counterculture. Only the first and last rooms of the large show are explicitly devoted to political memorabilia. The main body of the exhibit seems devoid of them, which fits well with the story told in so many history books. The hippies of that era, so it’s often claimed, paid scant attention to political matters.

Take another moment in the presence of all the artifacts of that psychedelic summer, though, and a powerful (if implicit) political message actually comes through, one that couldn’t be more unexpected. The counterculture of that era, it turns out, offered a radical challenge to a basic premise of the Washington worldview, then and now, a premise accepted—and spoken almost ritualistically—by every president since Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Nothing is more important than our “national security”…

The most widely read San Francisco intellectual of that year, Alan Watts, caught the moment (and pushed it yet further) in the very title of his book, The Wisdom of Insecurity. He spelled out what the light shows and posters communicated in a flash: What we think of as separate places, inside and outside, are merely two intertwined parts, two different ways of describing a single reality. Ditto for self and other, friend and enemy, life and death. The pursuit of security, he suggested even then, creates an illusory separation between friend and enemy in an effort to protect the self and life against the other and feared death. It is, he insisted, always doomed to fail, since all those opposites are inseparable. And ironically, the more we fail, the more frightened we become, and so the more frantically we pursue both the walling off of others and the illusion of security. Far wiser and more life-enhancing, Watts concluded, was to accept the inevitability of insecurity, the truth that in the stream of life, the next moment is always as unpredictable as it is uncontrollable.

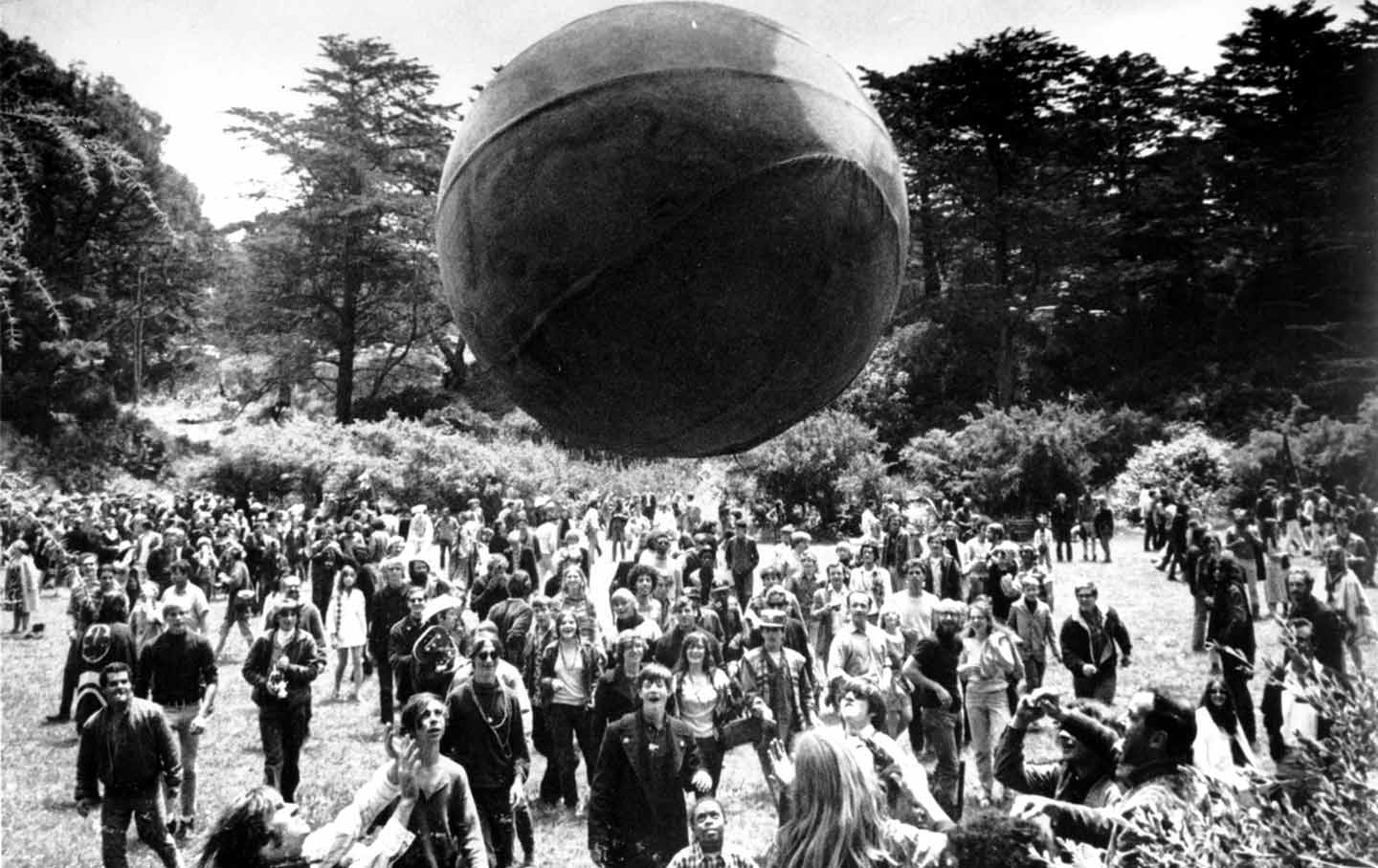

Image: The first day of the Summer of Love, San Francisco, June 21, 1967.