Darren Ambrose is a film scholar, filmmaker, and editor of k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016), forthcoming this fall from Repeater Books. At the Repeater blog, Ambrose has a moving piece about rereading George Orwell’s 1984 after the election of Donald Trump and finding unexpected consolation in the text. The consolation comes from encountering a new introduction to the novel by Thomas Pynchon that was added to the latest Penguin edition and that completely transforms Ambrose’s understanding of the book. Here’s an excerpt from his piece:

If Pynchon’s first observation altered my understanding of Orwell’s novel, his second had a more powerful existential affect. It seemed directed at all of the feelings I was returning to the novel with, right now. In an uncanny way it seemed to be speaking very directly to me. Pynchon’s introduction, written in 2003, does seem oddly attuned to our current times, and if one didn’t know any better one might believe that it was written for all of those who, like myself, would one day soon come running back to Orwell’s novel from the dystopian streets of the present. Pynchon takes the opportunity to remind us that this is not merely a bleak novel of dystopian confirmation, but a dire warning about the road that will take us there, a journey of seemingly inevitable ruin infused with a strange seed of redemption and hope. Orwell’s novel, he argues, is redemptive science fiction. I returned to Nineteen Eighty-Four wanting to immerse myself in a static and fatalistic analysis of totalitarian dystopia; Pynchon prevented me from doing that. It provided me with an abrupt interruption and a shift of perspective where I caught a glimpse of the simple possibility of an alternative future. This is a future rooted in the redemptive humanism of a child’s smile that emanates from an ‘unhesitating faith that the world, at the end of the day, is good, and that human decency, like parental love, can always be taken for granted.’ In fact, it was confirmation of this, something that I know intimately from spending every day with my own young son as he slowly comes to terms with, and navigates his way around, the world, that immediately sprang from my rereading of Nineteen Eighty-Four. That was not quite the confirmation I had expected. The first time I read Pynchon’s thoughts on the photograph it brought to mind something the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze had written in his final published essay ‘Pure Immanence’, which had also made a deep impression upon me when I read it over fifteen years ago. There he writes of small children:

Very small children all resemble one another and have hardly any individuality, but they have singularities: a smile, a gesture, a funny face – not subjective qualities. Small children, through all their suffering and weaknesses, are infused with an immanent life that is pure power and even bliss. (Deleuze, ‘Pure Immanence’, p. 30)

Equally, the smile of Orwell’s son in the photograph is not simply a subjective quality. As Pynchon suggests, it is emblematic of something immanently powerful, something singular ‘worth even more than anger’. It is nothing less than life expressing itself through the indomitable gestures of the child. And it is this indomitability which grounds the sheer nihilistic dystopia of Nineteen Eighty-Four as a warning rather than an historical inevitability. The smile of life is the unassailable light in the darkness, the intangible, imperishable and enduring substance in the nothing of the now. My own son is the same age as Orwell’s in this photograph, and as I read the introduction, I felt an instinctual truth in Pynchon’s observations. They ignited something new in my mind, not dormant or forgotten, but something else. Something new, unsuspected and alive. Amid the hopelessness and despair I was feeling post-Trump, his words actually confirmed something else, something different, something other than the darkness of the present. And it is simple, like a pure sober note rising out of the cacophonous discordant noise of the present crying “Look for the smile, listen for the laughter”.

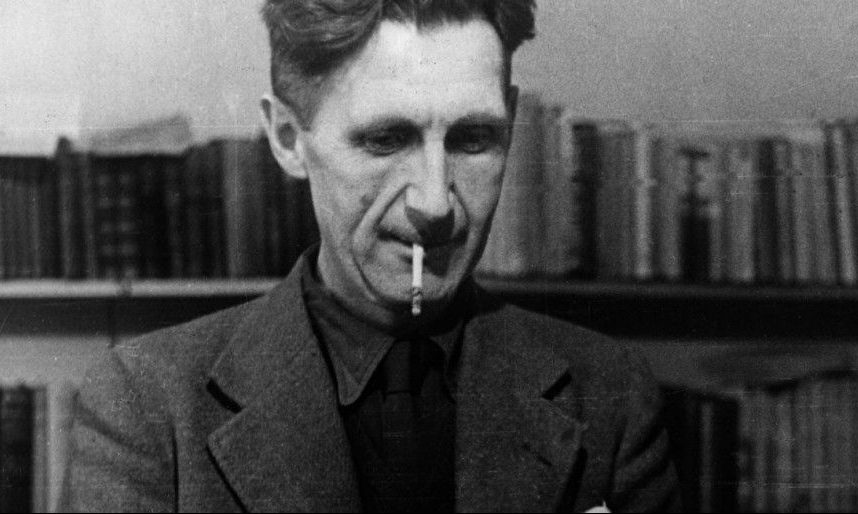

Image of George Orwell via Jacobin.