Writing for the New Inquiry, Gabrielle Dacosta reflects on the “intercommunalism” of Huey Newton, a cofounder and leading intellectual of the Black Panther Party in the US. As Dacosta writes, Newton’s theory of intercommunalism traces how social institutions that are responsible for maintaining the health and vibrancy of specific communities (in Newton’s example, African-Americans) are instead commandeered to serve the interests of a small social elite. Dacosta maintains that Newton’s theory is integral for explaining continuing racial disparities in US cities today. Read an excerpt from Dacosta’s piece below, or the full text here.

One of Newton’s major theoretical innovations was the idea of “intercommunalism.” He used this concept to characterize the ideological position of the Panthers in 1970. In brief, Newton claimed that due to the nature of imperialism, the nation had ceased to exist as the organizing principle of the world. Rather, power had been concentrated into the hands of a small ruling circle who then exerted a homogenizing influence around the world. In a speech delivered at Boston College in 1971, Newton defined the “community” as “a comprehensive collection of institutions which serve the people who live there.” The ruling circle of the world, he claimed, had expropriated many institutions from the communities of the world, such that they no longer worked in the interest of the people but rather worked for the rulers …

Newton observed that the ravages of imperialism had created this vast world of the underserved, which had in turn engendered unique opportunities for a kind of fluid solidarity beyond misleading and antique notions of national boundaries. Such insights seem perceptive, and even iconoclastic, in light of the dominance of internationalism in the radical political thought—particularly anti-imperialist and Marxist strains—of the ’60s and ’70s. The Panthers called themselves “revolutionary intercommunalists” in order to distance themselves from traditional socialist “internationalist” labels, which reaffirmed and legitimated the idea of the nation. Calling themselves “intercommunalists” allowed the Panthers to frame the importance of the community in relation to a revolutionary vision for the wider world. It allowed them to retain a grasp on the local when the rest of radical thought seemed to be moving global. Such insight pivoted upon Newton’s critical observation about the state’s neglect and abandonment of the black American community. From this, Newton was able to identify simultaneously what the imperialist project had wrought for the subjugated peoples of the world.

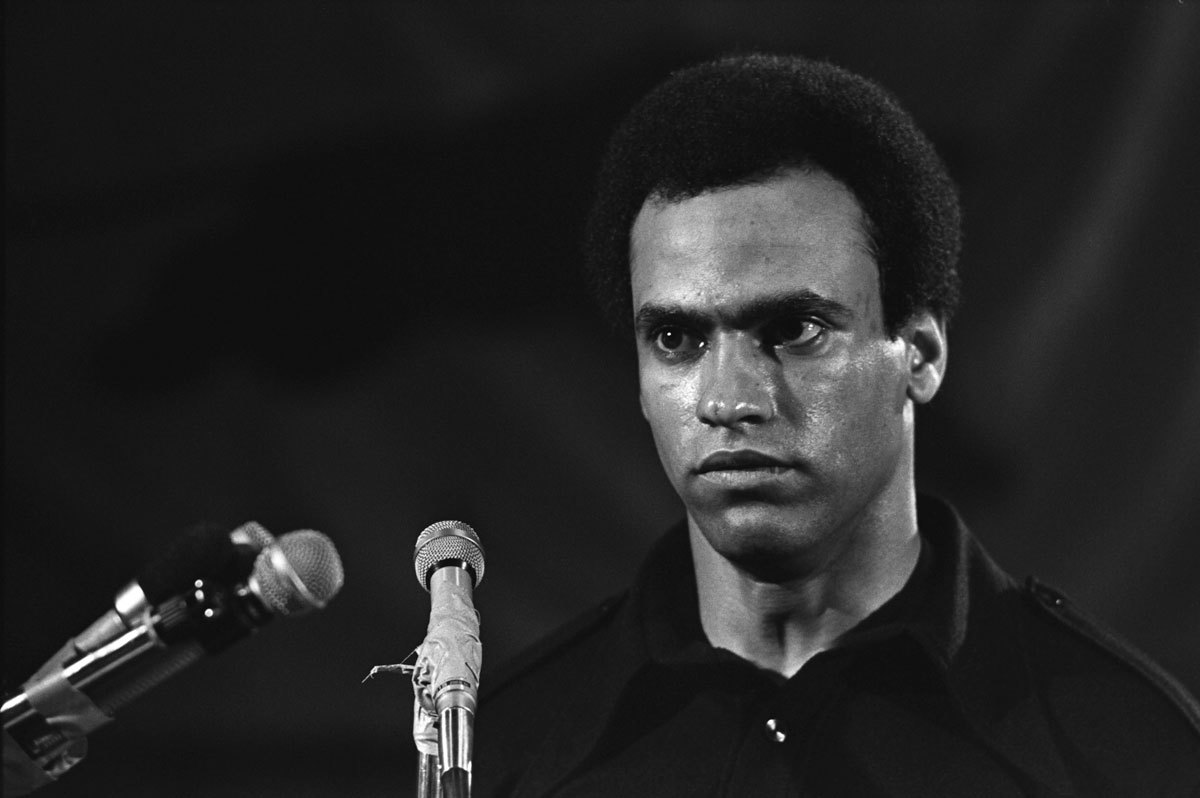

Image: Huey P. Newton