For the New York Times, Wil S. Hylton writes a profile on Chuck Close. Close, reports Hylton, has embarked on a new phase in life, ending a decades-long marriage and embarking on a new style of portraiture. Read Hylton in partial below, or in full via New York Times.

A couple of weeks ago, I went to visit Chuck Close at his beach house on Long Island. The drive there always reminds me of an escape to the Hamptons in reverse. From the aristocratic brownstones of Park Slope, you work your way steadily down the socioeconomic ladder, past the towering Soviet-style apartment complexes of Coney Island, through strips of pawn shops and gimcrack hotels that give way to rowhouses fronted with plaster statuary, until at last the journey comes to an end at the sun-beaten waterfront of Long Beach, a haven for cops and firefighters looking to blow off summer steam, where you pay for access to the sand amid a throng of rented umbrellas and creatine-engorged pectorals, all of which vanish at sundown into a surfeit of bwomp-bwomping nightclubs along the strip.

If all this sounds like an odd place to find one of the world’s most celebrated painters, a master of the modern portrait whose work is displayed in the great museums, all I can tell you is that pretty much every close friend and relative of Close’s feels the same way. After 30 years of splitting his time between the tony enclaves of Manhattan and Bridgehampton, he has recently set about leaving much of his old life behind: filing for divorce from his wife, Leslie, after 43 years of marriage, disappearing for the winter to live virtually alone in a new apartment on Miami Beach and retreating from his summer friends to the crowded isolation of Long Beach. Even when Close ventures into the city for a gallery opening these days, he will often turn up in some outlandish costume, in fabrics printed with giant starfish and sunflowers, with lipstick smeared across his face and billowing, extravagant scarves.

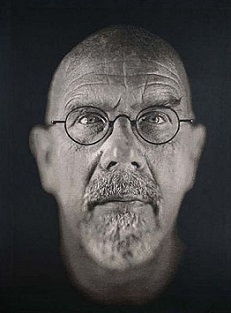

Over the past year, I have been stopping off to see Close in various homes and apartments up and down the Eastern Seaboard, trying to get a handle on the changes in his life and their connection to his work. On my most recent visit to his beach house, I arrived a few minutes early, and one of his assistants let me in, gesturing toward a staircase that leads to his bedroom and studio. I found Close waiting at the top with a gentle smile. At 76, it must be said, he is starting to look run-down. Apart from the obvious fact of his being restricted to a wheelchair since 1988, when an arterial collapse left him mostly paralyzed from the neck down, he is also entering that awkward phase in life when bodies degenerate unevenly, so that even as he’s become a little corpulent at the middle, his cheeks are starting to hollow out and his powerful neck to narrow, giving the impression that his shiny bald head and tufted white goatee are elongating with time. What hasn’t changed, and mercifully so, is that smile. It is the most hopeful, eager, childlike smile a person can imagine. It would not be going too far to say that it can fill and break your heart at once. Another element of lingering beauty about him is the contour of his wrists and hands. Thirty years of muscular atrophy have left them as stretched and sinewy as fine silverwork, and with only the slightest motor control, he tends to hold them perfectly flat, gesturing this way and that with all five fingers at once. The effect is vaguely regal. When he needs to pick something up, he will pinch it between the outer edges of his palms, which gives the impression of a man cupping water from a stream.

On this particular morning, he wore a paint-splattered smock over a white T-shirt and blue pants, swishing a small glass of cappuccino with both hands. After a quick hug and hello, we went outside to a balcony overlooking the water. The morning sun raked over the dune grass, and the beach was just filling with tourists. Close leaned back in his chair to let the light pour onto his face. He looked tan and rested, healthier than I’d seen him in months, and had been working all morning in the studio behind us on a large self-portrait that I knew he was excited about.

“I always have at least one self-portrait in each show,” he said, “but usually no more than one. And then, with the last show, there were a lot of self-portraits, and I’ve only done self-portraits since then. I think I’m having a conversation with myself.” He continued: “Facing death, or whatever the hell it is. I think it comes out of my diagnosis and not knowing how long I have.”