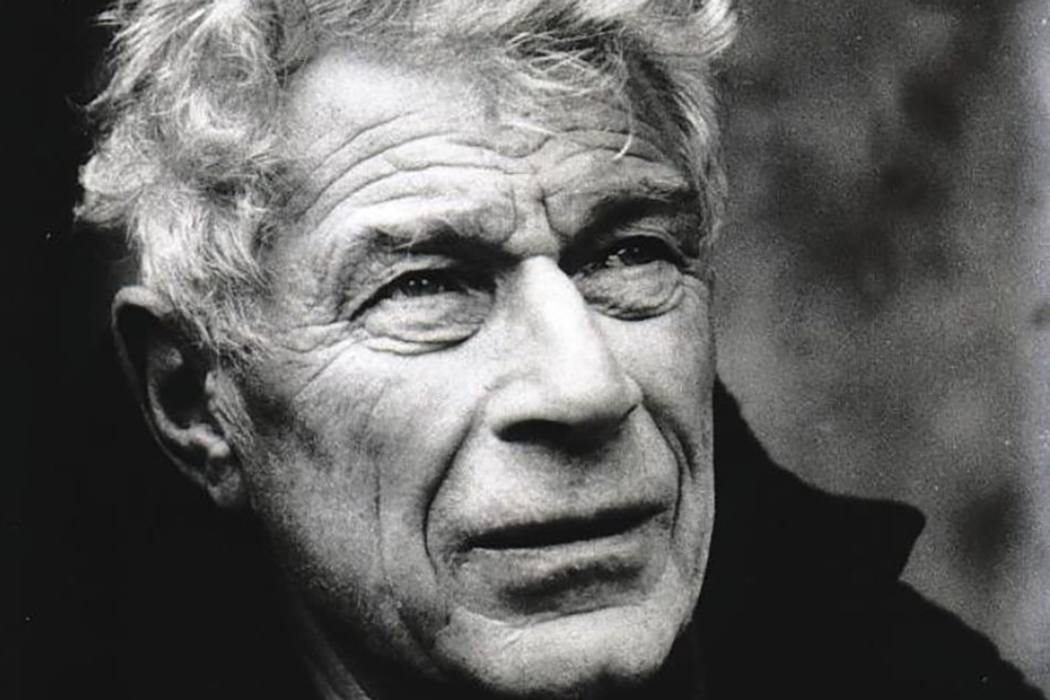

Influential art critic and novelist John Berger died last year after a long and eclectic life. In the Los Angeles Review of Books, Robert Minto reviews the first posthumous biography on Berger, A Writer of Our Time: The Life and Work of John Berger by Joshua Sperling. The book, writes Minto, is a worthy treatment of a man whose writing ranged over a great many styles and subjects but never wavered from its commitment to uncovering the revolutionary dimension of art. Here’s an excerpt:

Seeing, more than anything, was the substance of Berger’s career. It extends backward to his first creative aspirations as an artist. He never gave up sketching, often including his drawings in later books. Seeing also formed the method for his essays, where he often describes an act of seeing and the thoughts that arose from it.

While Berger’s range as a writer was broadening and his thinking as a critic deepening, he also transformed his life. It is here that I wish Sperling had been more detailed, and explored the influences on and specifics of Berger’s personal life, but he does give us a glimpse:

At the start of the [1960s], it had been as if Berger was shifting his weight from one foot to the other, testing the balance of a new, more Mediterranean bearing — further from the chattering classes but closer to the land and to history — before making the final jump. As the sixties swung towards its apogee he made the jump: he committed to it. He passed weeks in a stone hovel in the shade of the Luberon mountains, among fig trees, fruit orchards, chickens, dogs, cicadas and owls, working the land in the morning and reading philosophy in the afternoon. It was a new life of continental thought and feeling — the feeling of thought — he had found (and curated) for himself, a life of lavender and onions, terra cotta and shared meals. He took philosophical modernism outdoors, letting it bronze his skin. In the process, he tried to live out what [Martin] Heidegger had called for but may never have personally achieved: the return of philosophy to life. The revolution had to be lived all the way down.

It’s odd that Sperling cites the Nazi philosopher Heidegger here when the thinker whose vision of life is called up and even echoed in Sperling’s sentences is Karl Marx. Marx described the communist vision of the good life this way: “[I]t [becomes] possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind.” Berger seems to have sought out a way of life that prefigured this utopia. Later, he would fully commit to it, settling down in the rural village of Quincy, outside Geneva.

Image of John Berger via JSTOR Daily.