At the New Yorker website, Anna Wiener pages through old issues of Wired magazine, which published its first issue in April 1993, to discover what the tech-geeks of that era imagined the internet of our era would be like. She finds that the magazine was startlingly prescient, envisioning devices much like today’s iPad and Amazon Echo. But what was not carried into the future was the insubordinate, psychedelic spirit that animated much underground internet culture in the Nineties. An excerpt:

I became engrossed in an article from 1993 by Steven Levy, “Crypto Rebels,” which described “a war going on between those who would liberate crypto and those who would suppress it.” The outcome of the struggle, he wrote, “may determine the amount of freedom our society will grant us in the 21st century.” More than two decades later, the struggle over encryption continues; digital freedoms still hang in the balance. There’s a lot of chatter in Silicon Valley about changing the world, but our own world hasn’t changed that much.

All of this has made me feel not just nostalgic but a little wistful. As much as my Wired archive is a document of its era’s aspirations, it’s also a record of what people once hoped technology would be—and, in hindsight, a record of what it might have become. In early Wired, a piece about a five-hundred-thousand-dollar luxury “Superboat” would be followed by a full-page editorial urging readers to contact their legislators to condemn wiretapping (in this case, 1994’s Digital Telephony Bill). Stories of tech-enabled social change and New Economy capitalism weren’t in competition; they coexisted and played off one another. In 2016, some of my colleagues and I have E.F.F. stickers on our company-supplied MacBooks—“I do not consent to the search of this device,” we broadcast to our co-workers—but dissent is no longer an integral part of the industry’s ethos.

Today’s future-booster events, like the annual Consumer Electronics Show, tend to prize stories of novelty and innovation—and yet, reading early Wired, it becomes clear that many of the inventions that claim to be new today are simply extensions of what came before. A sidebar on Wacom’s ArtPad, from 1995—“If you’ve ever sketched with a pencil, you’ll be able to use ArtPad”—made me wonder why it took Apple so long to roll out its Pencil stylus for the iPad. A 1994 article on continuous voice recognition—a core component of responsive products, like Amazon Echo and Apple’s Siri—effused, “IBM has some mondo hot technology on its hands here.” (Google, Microsoft, and Nuance Communications seem to have caught on since.) Early versions of 3-D printers, endless varieties of virtual-reality headsets, and remote-controlled, camera-laden helicopters abound. Perhaps the heart wants what it wants, and the heart has always wanted V.R., A.I., drones, and entertainment straight to the face.

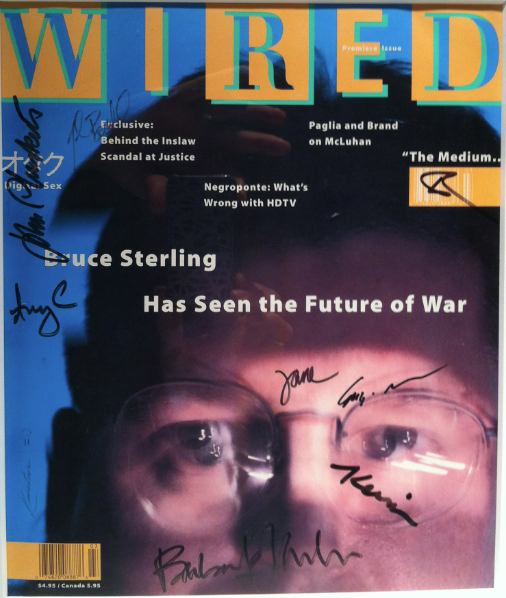

Image: The first issue of Wired.