Public Seminar has an excerpt from the book Penis Envy and Other Bad Feelings: The Emotional Cost of Everyday Life by theorist Mari Ruti. The book uses the psychoanalytic theories of Freud and Lacan, combines with personal reflection from Ruti herself, to examine the sociopolitical foundation of everyday “bad feeling” like anxiety, depression, and anger. In the except, Ruti explains the notion of a “portable phallus,” which gives its bearer the illusion of being exempt from the helplessness and abjection at the core of human life. Check out a snippet of the excerpt below or the full text here.

One of the many things I appreciate about Lacan — and this is what some of my fellow feminists misunderstand about him (because he’s not always easy to understand) — is that he illustrated that phallic authority is always a masquerade, regardless of who displays it. Men can pretend to possess this authority because they have a penis, but in actuality they don’t have it any more securely than women do; in actuality, they’re just as “lacking,” as fundamentally woundable — “existentially,” psychologically, emotionally, and physically vulnerable — as women are.

To emphasize this point, Lacan even used the term castration as a synonym for this woundability, suggesting that castration, metaphorically speaking, is the human condition. Although Lacan was far from a feminist, he gave feminist theorists a lot to work with when he declared that men are just as “castrated” — lacking — as women are.

Like his contemporary Jean-Paul Sartre, Lacan was interested in the lack — the encroaching nothingness — that gnaws at the foundations of human life; he was interested in the feeling of emptiness that often permeates our being even when things are in principle going fine. His explanation for why we feel this way was developmental. He hypothesized that the void at the heart of human subjectivity is an inevitable byproduct of the process of socialization that molds an infant — who is initially a creature of unorganized bodily functions — into a culturally viable being, into a child who understands the basic codes of behavior that she’s expected to adhere to. This process is necessary because it allows the child to become a member of her society.

But it comes at a price: it forces the child to encounter a symbolic world of meanings that she has had no part in devising; it throws her into a vast universe of complex (and often enigmatic or inscrutable) signifiers, including language, in relation to which she’s asked to find her bearings. This experience, according to Lacan, is intrinsically humbling, bound to make the child feel inadequate to the task. Because children can’t always fully process the signifiers that surround them, including what adults are saying to them (or around them) — because they can’t always figure out what adults want from them or why adults want certain things done in a certain way — they’re never able to feel completely in control of the universe they inhabit. This feeling of failure lingers into adulthood, making each newly minted human being feel like it has lost something precious, like a piece of its being is missing.

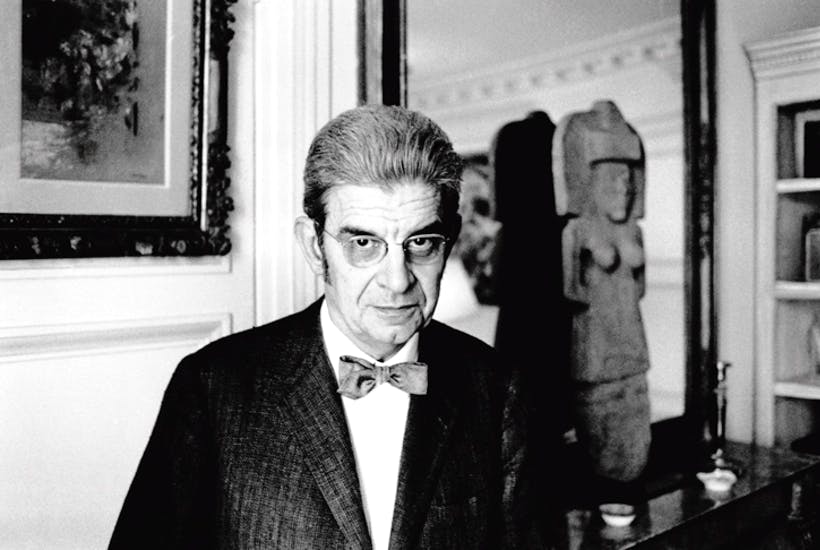

Image of Jacques Lacan via The Spectator.