In the December-January issue of Bookforum, Dennis Lim, the director of programming at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, pens an appreciation of Robert Bresson and a review of the auteur’s manifesto-cum-technical manual, Notes on the Cinematograph, newly translated by New York Review Books. Lim writes that Notes is both a fascinating window into Bresson’s rigorous filmmaking style, and a larger philosophical reflection on the possibilities of cinema as an art form. Read an excerpt of the piece below, or the full text here:

In four decades, Bresson made only thirteen features, works of extraordinary lucidity and profound mystery, of absolute rigor and overwhelming emotion. Most of his characters—who include an imprisoned resistance fighter (A Man Escaped), an obscurely motivated petty thief (Pickpocket), and a suicidal young wife (A Gentle Woman)—are searching for a liberation of sorts, whether or not they know it, and most of his films assume the form of a quest for the essential, for a state of grace. Bresson came to movies late, having started as a painter, and he would attempt to exercise as much control over a collaborative, industrial medium as an artist has over his canvas. His allergy to compromise meant that the films were few and far between. Reflection, whether by inclination or necessity, was part of his process. “Precision of aim lays one open to hesitations,” he writes in Notes, which he took several decades to complete, adding that Debussy would spend a week “deciding on one chord rather than another.”

Many of Bresson’s “notes” are mere sentence fragments: “Unusual approaches to bodies.” “Not artful, but agile.” Some, more carefully honed, resemble Zen koans: “Empty the pond to get the fish.” Others take the form of concrete imperatives: “When a sound can replace an image, cut the image or neutralize it.” There are kernels of pragmatic advice, as when he extols the value of the “small subject” that allows for “many profound combinations” (with bigger themes, “nothing warns you when you are going astray”). And befitting his taste for contradiction, there are paradoxes aplenty. “Put oneself into a state of intense ignorance and curiosity, and yet see things in advance,” he writes, splitting the difference, as did many of his films, between chance and predestination.

While the tone verges on didactic, these are less cardinal precepts than notebook jottings, albeit highly methodical and developed ones that add up to an original philosophy of composition, editing, sound, and acting in cinema. Many of these ideas were repeated and expanded on in his occasional encounters with the press, a selection of which can be found in the newly translated Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943–1983. Presented chronologically, these profiles and conversations reveal occasional refinements of thought—evolving attitudes to color, say, and to casting—but on the whole attest to the remarkable coherence and consistency of his body of work.

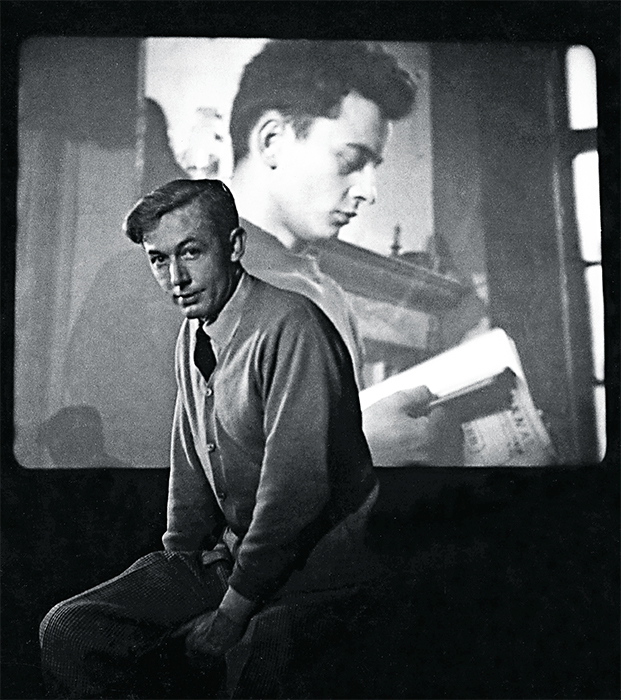

Image: Robert Bresson at a screening of Diary of a Country Priest, ca. 1951. Via Bookforum.