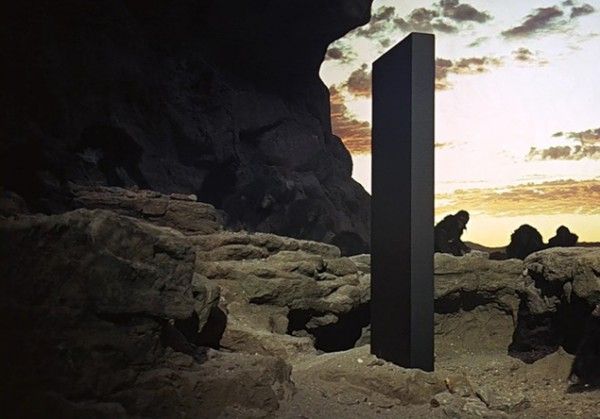

At the Baffler website, Gene Seymour has a poignant and personal piece that expresses nostalgia for the era when space travel stoked our fascination with the universe and made us ask deep questions about our own place in it. While acknowledging that twentieth-century space travel was as much about Cold War rivalry as exploring the unknown, he still longs for the spirit of discovery and curiosity that animated that age, as found in movies like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. As Seymour notes, today space travel has largely shifted from a government project to a private enterprise, with discovery taking a back seat to profit. Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

Still, I’d have rather flown to Jupiter by now. That’s just me. And I’m perfectly willing to accept the possibility that a spacefaring world would be no better than the one we live in now; that it may have retained most of the polarities between countries and tribes that in different ways threaten peace, justice, and democracy. But even the most dystopian science fiction retains a subversive belief in the future’s ability to make us different from whatever we are now. That may not be logical. Faith rarely is. And in both the things it explains and the things it leaves open for speculation, 2001: A Space Odyssey remains after a half-century the most persuasive and compelling expression of that faith; not despite its ambiguities, but because of them. The open spaces it leaves to imagination may not satisfy those who prefer whatever passes for the Well-Built Movie. Some works of art, even grand desperate voyages like those chronicled in Moby-Dick, require abandon and acceptance of even their more outrageous inventions. Not all blanks can be filled immediately.

But what would happen if we just said, “Screw it,” to any notion of moving beyond our narrow planes of existence? This, too, is a “what if” query that science fiction engages, and among the better, if somewhat drastic, depictions of such prospects is “Myths of the Near Future,” the title story of a 1982 collection by the late British fantasist J.G. Ballard (1930-2009), whose acerbic, post-apocalyptic visions of alternate worlds and surreal societies made him a near-polar opposite of the more utopian and optimistic Clarke. “Myths” is set in a dense, swampy, near-abandoned Florida coastline region where the gantries and launch pads of Cape Canaveral (referred to by its temporary name of Cape Kennedy) have been rusted and inactive for decades. Those now inhabiting the region wander aimlessly as if in a dream state. Some fly and crash airplanes. Others stay locked in motel rooms or sit outside staring at dry swimming pools clotted with weeds and debris. They suffer from what Ballard refers to as “space sickness” blending an immobilizing nostalgia for the space age with an impulse towards long-term hibernation.

Image: Still from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.