Writing in Pacific Standard magazine, Rick Paulas examines the ethics of life-extension science in a modern world sharply divided by class. Even absent live-extension technologies, the existing difference between the life expectancy of someone born into a rich country and that of someone born into a poor country is staggering. How can life-extension technology avoid simply widening this divide? Is it even ethical to develop life-extension technology at all?

Here’s an excerpt from Paulas’s piece:

The argument for life extension is obvious: People get to live longer and, theoretically, healthier lives. And the argument for extension techniques being used by the rich is also obvious: They can afford it and the poor can’t. (They’re also kind of strange about how they go about doing it.) But as a society, we need to consider the moral implications of a world where the lifespans of the rich and poor are so dramatically different.

In 2007, Martien Pijnenburg and Carlo Leget tackled “three arguments against extending the human lifespan” in a paper for the Journal of Medical Ethics. Their first argument regarded the moral problem of “unequal death”—that is, the different realities between First and Third World countries when it comes to life extension. “Our efforts to prolong life ought not to be separated from the more fundamental questions relating to integrity,” they concluded, “given the problem of unequal death, can we morally afford to invest in research to extend life?”

In other words, what has more value: high-priced research that allows a certain segment of the population to live longer? Or aiming budgets at trying to raise everyone’s lifespan by focusing on clean water, eliminating diseases, and finding cheaper ways to deliver life-saving surgeries to the poor?

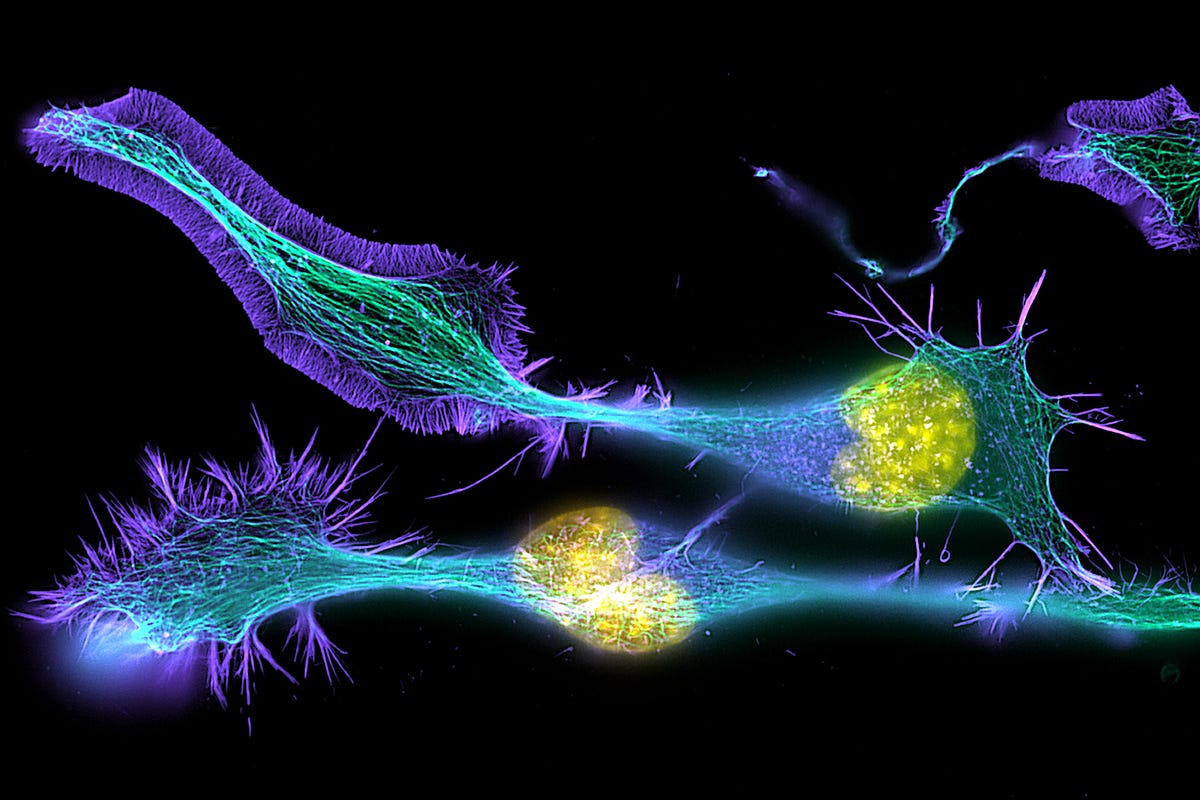

Image via Pacific Standard.