In the fall issue of Bookforum, Lidija Haas reflects on the new book Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger by US journalist Rebecca Traister. In the book, Traister examines the surge of publicly expressed rage coming from women in the wake of Trump’s election and the emergence of the #MeToo movement. She calls this rage a powerful and even “revolutionary” force, especially considering that women are socialized to express anger carefully in circumscribed ways, when they’re allowed to express anger at all. But as Haas argues, anger alone, now matter how fervent, is not revolutionary; it must be wedded to an organized movement for social transformation. Here’s an excerpt:

Traister’s thesis seems at first a seductively straightforward one. She argues that the rage of “nonwhite non-men” as a political force has so far not been given anywhere near its due in American history and culture, that it has been responsible for a significant portion of progressive change in this country, and thus that the newish angry-woman constituencies fired up by the 2016 election (many of them white and comfortably off) are part of a proud lineage, and should be celebrated and encouraged. It’s an intriguing double move—giving women of color their rightful, pioneering place in feminist and progressive history while also insisting on the automatic right of white liberal feminists to be directly identified with a more radical tradition.

Anger is an inherently unstable compound; that’s part of its power. It’s a feeling—at its best, a place to start from, a raw material to be interpreted, analyzed, and acted on. Feminist anger can be the initially inchoate sense that conditions one has been forced to live with as normal or natural are in fact both deeply wrong and fundamentally unnecessary—a reaction Sara Ahmed has termed “snap.” As Audre Lorde put it in her brilliant 1981 piece “The Uses of Anger,” rage is “loaded with information and energy,” and so can function as both an interpretive tool and a fuel for ongoing action. Lorde also warned, though, of the care and honesty required to use one’s anger for the collective good—solidarity involves hard and delicate work. “What woman here is so enamoured of her own oppression that she cannot see her heelprint upon another woman’s face?” she wrote, counseling against hiding in “the fold of the righteous, away from the cold winds of self-scrutiny.” At the heart of Traister’s project, then, lies the question of who is angry and about what, whether anger in itself necessarily points to shared interests and goals, and whether women’s anger always bends toward the righting of injustices.

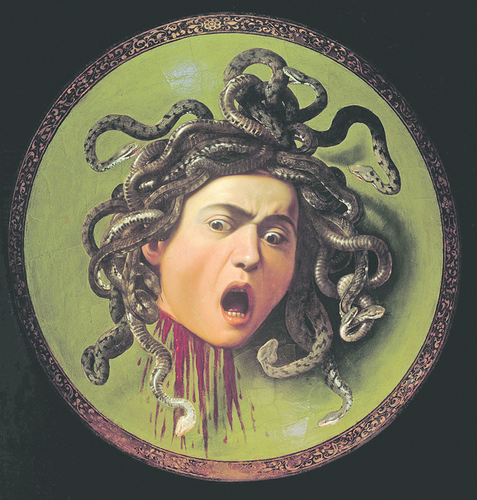

Image: Caravaggio, Medusa, ca. 1597. Via Bookforum.