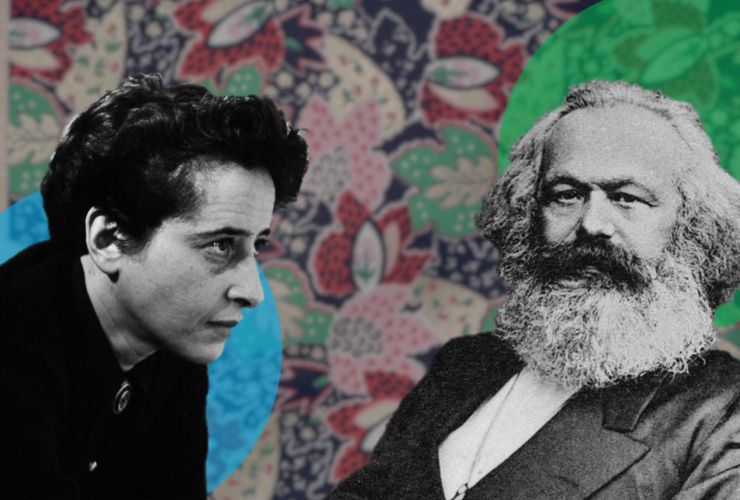

In the Boston Review, scholar of German studies Geoffrey Wildanger evaluates Hannah Arendt’s posthumous book Karl Marx and the Tradition of Political Thought. Assembled from the fragments of the unfinished manuscript, it was recently published for the first time in German. As Wildanger notes, among historians and theorists Arendt and Marx have long been positioned on opposite sides of a political divide: Arendt as a liberal, favoring gradual social change and wary of radical upheaval; and Marx as a revolutionary, organizing for the revolt of the masses. But Arendt’s posthumous book complicates this simple distinction, as Wildanger explains. Here’s an excerpt:

The new volume on Marx will force scholars to reevaluate some of their presumption. By arranging some essays that Arendt ultimately published, such as “Understanding and Politics,” within their chronological context along unpublished pieces, such as “Karl Marx and the Tradition of Western Political Thought: The Modern Challenge to Tradition,” the editors piece together the material for a book length study that ventures into the profound territory laying in between The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition . The book makes clear Arendt’s deep regard for, and apprehension at, the revolutionary claims of Marxism. Like Marx, Arendt understands revolution to be the product of the disjuncture between modernity’s ideals of justice and equality and the realities of capitalism. Like Marx, she recognizes the “mute violence” of the marketplace. Nonetheless, she doubts Marxism can avoid the Büchner problem: the terrors of revolutionary violence. Occasionally she remains stuck in the clichés of Cold War polemic, and here her reading of Marx can be weak. But where she breaks with this blindness, she develops brilliant insights.

The essence of Arendt’s disagreement with Marx is the importance she places on the question of political rights above social ones. She develops this priority most extensively in On Revolution (1963). Elizabeth Young-Bruehl, her biographer, cites a review by Michael Harrington, who would go on to found the Democratic Socialists of America, as representative of the Marxist reception. Though he accepts the arguments of the latter half of the book, with its praise of Rosa Luxemburg’s “council communism,” Harrington rejects the argument upon which Arendt’s praise rests: the priority of political rights over social amelioration. In our post-Occupy era, the starkness of Arendt’s dichotomy may strike us as exaggerated, yet she stuck to it. Late in life, when her friend Mary McCarthy asked her why certain social matters could not simply be defined as rights (health care, say), she dodged the question. For Arendt, the fundamental distinction is between the private and the public spheres. Attempting to politicize the private, she believes, will more likely subjugate politics to economics than vice versa.

Image via Boston Review.