At Public Books, historian David Henkin reviews Reading and the Making of Time in the Eighteenth Century (2018) by Christina Lupton, which explores how readers and writers during the rise of mass reading used books to manipulate, mark, and resist time. As Henkin notes, eighteenth-century readers treated books partly as an escape from regimented wage-labor time. This is not unlike the way books today—especially novels—are held up as a countervailing force to the ceaseless acceleration of digital time. Here’s an excerpt from Henkin’s review:

Acceleration, distracted attention, and the death of leisure: all three diagnoses of the crisis of the moment hinge on time. Against the backdrop of the current cultural complaints, Christina Lupton, who teaches English literature at the University of Warwick, turns her attention to England during roughly the second half of the 18th century in an effort to explore the relationship between reading books and spending time. This historical move is unsurprising, not only because that’s where Lupton’s scholarly and critical expertise lies but also because the era of Enlightenment (broadly defined) in Western Europe has been the most frequent landing spot for book historians and media theorists looking for precedent dislocations of the written word that, today, are produced by electronic text transmission and the internet.

What makes Lupton’s thoughtful and learned new book, Reading and the Making of Time in the Eighteenth Century, so interesting is not that she has recovered 18th-century literary figures dealing with proliferating reading material, diversifying formats, and accelerating production schedules, nor that those figures engaged in recognizable strategies of browsing, sampling, rearranging, and selective inattention—though she shows plenty of that, too. Rather, it is that she presents a set of exemplary readers and writers whose reflective encounters with books highlight the utility of the codex as a technique for thinking about time in its many meanings. The result is a vigorous and partially novel defense of the value of books and the humanities to a happy and meaningful life.

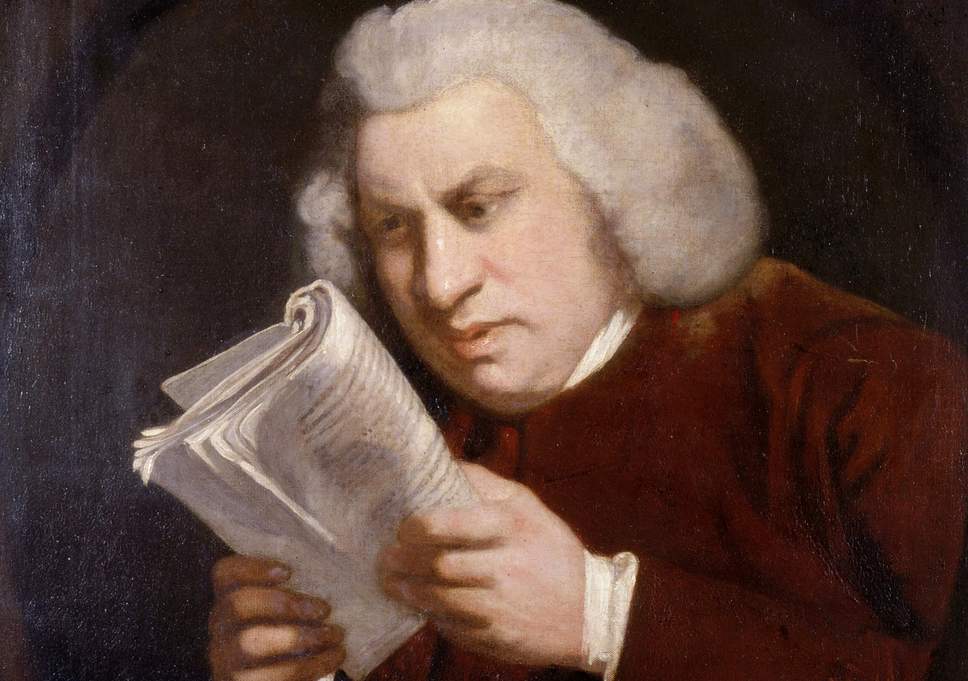

Image: Portrait of Dr. Samuel Johnson by Sir Joshua Reynolds, ca. 1772. Via the Independent.