What is contemporary art for? In the 2011 Q-Art London publication ’11 course leaders 20 questions’ – an insightful set of interviews with educators on the past, present and future of UK fine art pedagogy – John Timberlake (programme leader for Middlesex University’s BA course) provided an answer. ‘In the face of our predominantly utilitarian culture, I think art, at its best, is radically useless’ he said, ‘the radical quality of art is that it has no use in a culture dominated by profit, loss and use value’. Art as radically useless; surely that’s an expansive definition allowing for a democratic, progressive and less prescriptive field? Not so for the 2015 Turner Prize judges. For them utility was king.

Although no panel criteria for assessing an ‘outstanding contribution to contemporary art’ was published, an odd institutional mission statement cum manifesto was released by one judge: director of Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, Alistair Hudson. In ‘What is Art For’, a series of four online videos that feel like an extended, blue-sky sales pitch, Hudson talks through his conception of the ‘useful museum’, an institution whose categorical imperative is ‘to demonstrate what the real use of art is in society’. And what is the ‘real use of art’? According to Hudson it is to enact some vaguely determined social good, capable of bursting the image of art as a ‘separate bubble’. This bubble keeps art esoterically distant from the everyday lives of everyday people, and it all happened because of…wait for it…Romanticism. It is, Hudson says:

‘Like when you go in a gallery, when you go to a public participatory work or whatever it is, whatever kind of art output you experience. What is that? What’s it for? Why are you doing that?’

The useful museum filled with useful art will answer these questions before they’re posed. It will, like a huge, tool filled, multi-floor hardware shop, present you with an array of objects whose sole purpose is to perform some utilitarian function. This would all be fine as the inconsequential, ill-informed and slightly bizarre musings of a museum director selling audiences short to increase ‘footfall’ and ‘broaden audience reach’. But Hudson’s ‘out-of-the-box’ philosophy - a view apparently shared by fellow judges - has had a direct bearing on the result of this year’s Turner Prize. It was a decision that saw non-artists instrumentalised to introduce and legitemise the ‘useful’ ideology. It was a decision that could have seriously detrimental ramifications for British contemporary art.

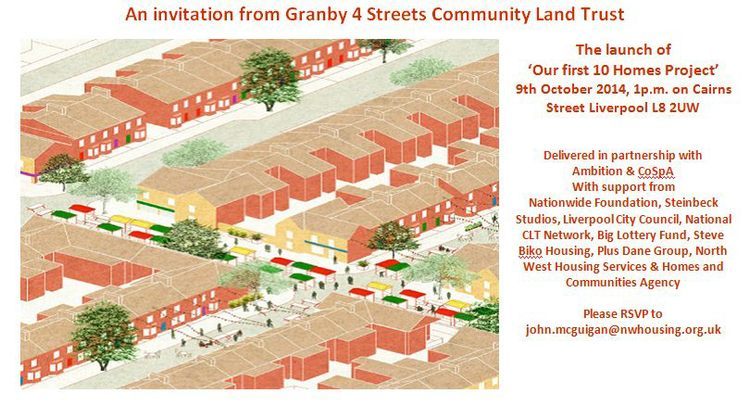

Assemble, this year’s winners, are a group of architects (not an artist collective) who were approached and employed by Granby Four Streets, a local grassroots organisation set up to develop and manage homes and other assets important to their immediate community, known as a Community Land Trust or CLT. Since 2011 the Granby Four Streets CLT has been locked in protracted negotiations with their local council. They have been trying to wrest private redevelopment plans for their area away from the commercial sector’s grip, and have over the past four years raised finances in order to carry out renovations themselves. You can read all about their work here. It’s an inspiring story of multicultural community activism and organisation that has its roots in the 1981 riots in the Liverpool area of Toxteth (provoked by police brutality and institutional racism), and the aftermath of willful housing stock neglect by the local council. Granby Four Streets are the lucky ones. People in other locations in the Toxteth area have been displaced, and left psychologically and emotionally scarred by long battles to stay in their homes and among their communities.

What happened in Toxteth is happening all over the UK. Families are being evicted, communities torn apart, and private developers erecting expensive new build properties on the rubble of sold off social housing stock – a process captured in artist Andrea Luka Zimmerman’s heart-rending film ‘Estate a Reverie’. In other words, there is a housing crisis in the UK. It’s a programme of social cleansing dressed up as ‘gentrification’, enacted and facilitated by government policies (both Labour and Conservative) that are designed to satisfy the profit driven bottom lines of property developers and the local councils selling their assets to them. This is the social context Assemble are being cast as engaging in. In fact, it is the social context that Assemble have been silent about, or rather unable to articulate, which may have something to do with that fact that they are not artists.

Although the reduction of technical-skills-based-learning in UK art education has led commentators to speculate on the deproffesionalisation of art, it is undoubtedly the case that rigorous conceptual training, in which the development of critical faculties is encouraged and challenged through discussion, group critique, lecture and written assessment, has taken its place. This has developed in response to a field that, since the 1960s, grew uncomfortable with its co-option by powerful governmental, financial, or ideological forces; a field that increasingly produced art that problematized and drew critical attention to its modes of display and exchange, not to mention the culture, society and politics that made that display and exchange possible.

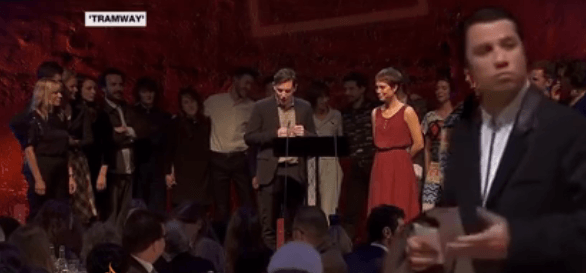

In other words, contemporary art is a critically engaged field that, for the most part, produces critically engaged actors who are uncomfortable with state power and its various methods of citizen subjection - this is nowhere more prevalent, diligently observed or else thoroughly critiqued than in socially engaged practice. Because Assemble are not and do not claim to come from this discipline, because they are not critically engaged, and because they are a firm of architects employed to creatively fulfill a design brief, however open, theirs is an acritical almost completely depoliticised response to a highly politicised social situation. Their submission for the Turner Prize exhibition at Tramway Gallery in Glasgow, Scotland, was effectively a showroom for the display of bespoke, domestic product design, with no reference to the political or social situation that led to their employment by the Granby CLT. And, at the point of receiving the award, when they had an opportunity to raise awareness of the situation in Toxteth on a national stage, they were unable to articulate a meaningful response. ‘We did consider that’ they’ve said in a recent Guardian newspaper interview ‘but what can you say in only 60 seconds that doesn’t sound gloating, or too pithy to understand.’

To see an inspired, cross-disciplinary response to the housing crisis in the UK take a look at the brilliantly ambitious and expansive landmark exhibition Real Estates staged by Fugitive Images, a group comprised of Zimmerman, artist Lasse Johaanssen and architectural theorist David Roberts. Or even consider the work of Architects for Social Housing (ASH) a collective of urban designers, engineers, planners, building industry consultants, academics, photographers, web designers, writers and housing activists, set up to respond to London’s housing crisis. Instead of looking to these instances of actual socially engaged practice, or even awarding the Turner Prize to the Granby Four Streets CLT and not their employees, the Turner judges have seemingly made a hollow, tokenistic gesture of pseudo-radical intent, instrumentalising a depoliticised architectural collective in order to drive home a point about ‘useful art’.

The fact is Hudson’s ‘useful’ model, and the judges privileging of utility over criticality, is a boon to the current Conservative government. Because at a time in the year when the British public, or at least British mainstream media attention is most focused on contemporary art, the field (that is a critically engaged discipline that challenges normative ideologies and creates contexts for challenges to state power) has effectively stuck two fingers up at itself. In the current national climate where public subsidy for the arts is being ruthlessly cut, where higher education for arts and the humanities is being turned into a business, and where artists and institutions are under pressure to make the economic case for art, it will undoubtedly send damaging ripples through the art world. How difficult will it be to make the case for projects, exhibitions and initiatives that resist quantification, challenge state power and provoke more questions than they do provide answers, now that policy makers will be able to point to the Turner Prize and cite contemporary art’s disenchantment with its own open ended nature?

This isn’t about the series of ‘but is it art’ straw men set up around this year’s award, it isn’t even about Assemble, who seem a chilled bunch who make nice looking products and constructions. It’s about the new conservatism of utility, and how the rhetoric of use values has been deployed to close down the same expansive, inclusive and progressive nature of contemporary art that enabled an architecture group to be nominated for the Turner Prize in the first place. But what do you think?

Were Assemble instrumentalised as part of an institutional endgame strategy?

Was it all part of Hudson’s plan to launch and legitimize the ‘useful museum’ model, whilst simultaneously inaugurating his age of ‘museum 3.0’, via a nationally recognised platform?

Should the Granby Four Streets CLT have won the Turner prize?

Is radical uselessness better than utility?

Should we ‘not care’ because the Turner Prize is just an award and it has no bearing on contemporary art, or is that a naïve position?

Is 60 seconds long enough to say something with some political weight to it?

Should more museums adopt a ‘3.0’ mentality?

Show quoted text

Show quoted text