In The Nation, Stephen Kearse reviews Exhalation: Stories, a new collection of tales by the celebrated US sci-fi writer Ted Chiang. As Kearse notes, mainstream entertainment’s recent turn towards sci-fi has too often focused on the slick tech and futuristic aesthetics of the genre at the expense of its philosophical and literary concerns. But Chiang’s writing is an antidote to this superficial sci-fi, writes Kearse. It’s exploration of grief, faith, and mortality in beings as diverse as robots, parrots, and humans is sci-fi at its most humane and artistically accomplished. Here’s an excerpt from the review:

Exhalation follows scientists, con artists, merchants, software designers, and even parrots across time, space, and dimensions. This impressive range and Chiang’s visible respect for his characters’ differences have led him to be characterized by some critics as a humanist, but that term fails to capture the ambition on display here. The collection’s title story, for instance, takes place in a universe where metallic beings powered by mechanical lungs learn that the planet they live on is encased in a sealed chamber, meaning the energy that powers them is finite. They had believed that their sky, and thus breathable air, was infinite. Following the second law of thermodynamics (entropy never decreases in a closed system), this revelation portends doom: With the air pressure marching toward a fatal equilibrium between the atmosphere around them and the argon they draw from an underground reservoir that gives them life, it will eventually reach a level at which all airflow and breathing will cease. “It will be the end of pressure, the end of motive power, the end of thought,” the narrator says.

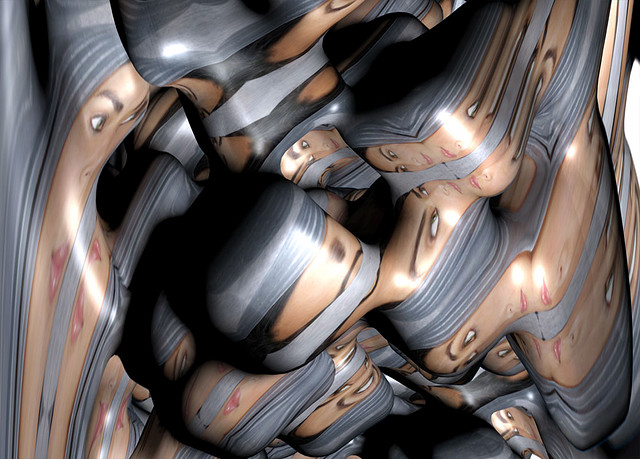

Chiang stages this grave news within a moment of surreal body horror. The narrator, an anatomist, discovers the truth of his universe by dissecting himself and observing the mechanisms of his brain. Recalling that strange moment, he says, “I saw that air does not, as we had always assumed, simply provide power to the engine that realizes our thoughts. Air is in fact the very medium of our thoughts. All that we are is a pattern of air flow.” As he processes this news, he sees his mind contemplating death: “Body locked in a restraining bracket, brain suspended across my laboratory…I could see the leaves of my brain flitting faster from the tumult of my thoughts, which in turn increased my agitation at being so restrained and immobile.” The scene is lurid and disturbing and strikingly inhuman. There’s an intimacy to the image of self-dissection, too, but it’s so foreign, so welded to the narrator’s particular anatomy and circumstances, that it resists becoming a human parable. This isn’t a story about peak oil or climate change; it’s about an irreversible catastrophe as experienced by a wholly alien life-form.

Image by Hidenori Watanave from Japan - Ted Chiang’s “Alchemist’s Gate.” Uploaded by PDTillman, CC BY 2.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.