In the January issue of e-flux journal, which was published earlier this week, Sven Lütticken offers a magisterial account of the history and present of autonomy as theory and practice in both art and politics. It’s a longread but a good one. Here’s a generous excerpt:

In the early 1980s, theorists of postmodernism observed and often ideologized an aestheticization of daily life via commodification in what seemed like a parody of old avant-garde ambitions, problematizing or flat-out rejecting Modernist theories of art as having a largely autonomous history in which the “unsolved antagonisms of reality” are reconfigured time and again as “immanent problems of form.” As the greatest Modernist aesthetician, Adorno had of course acknowledged that the autonomization of art was itself a consequence of the division of labor in capitalist society. However, for Adorno the faits sociaux enabling Modernist art are in the end just that; the art cannot be reduced to its heteronomous conditions. Film was part of the culture industry and needed sociological perspectives; one chapter of Adorno and Eisler’s book on film music is called “Sociological Aspects.” By contrast, art itself is a higher sociology; it is critical theory in the form of aesthetic objects. The fait social of modern art was ultimately articulated best on the level of the autonomous artwork, mimetically and fetishistically.

However, throughout the twentieth century a more purely sociological account of the autonomy of art, whose foundations were laid by Max Weber, gained traction. In his 1980 attack on postmodernism, Jürgen Habermas would rely on this Weberian model not so much to analyze as to defend modernism in art, and the “project of modernity” in general:

[Max Weber] characterized cultural modernity as the separation of the substantive reason expressed in religion and metaphysics into three autonomous spheres. They are: science, morality and art. These came to be differentiated because the unified world-views of religion and metaphysics fell apart. Since the 18th century, the problems inherited from these older world-views could be arranged so as to fall under specific aspects of validity: truth, normative rightness, authenticity, and beauty. They could then be handled as questions of knowledge, or of justice and morality, or of taste. Scientific discourse, theories of morality, jurisprudence, and the production and criticism of art could in turn be institutionalized.

While the sprawl of the field of art and art’s progressive institutionalization and capitalization fuelled neo-avant-garde protest during the 1960s, it also made gambling on a revolutionary break with the system seem increasingly unfeasible once the impetus of 1967–68 waned. What emerged very forcefully in this situation was a sociological turn in the form of those practices that later came to be known as institutional critique. Early protagonists of institutional critique such as Broodthaers, Buren, and Haacke rejected both the Modernist object and the avant-garde event or performance—both the Modernist conviction “that an object, by its distinction from all others, can serve as a mirror for an equally singular and independent subject” and the avant-garde belief in radically transgressive gestures that in fact leave the system intact and await their own institutional recuperation. Andrea Fraser has registered her doubts concerning “formulations that seem to reach for a kind of pure autonomy, a kind of pure freedom, in which avant-garde practices are sometimes identified with radical political practices, such as anarchist traditions and autonomia.” Much like Horkheimer and Adorno’s critical theory, institutional critique is an immanent critical practice in disciplinary and institutional frameworks—a series of interventions in their dialectics of enablement and constraints, their processes of subjectivation and subjection. Spectacular transgression was swapped for patient critical labor.

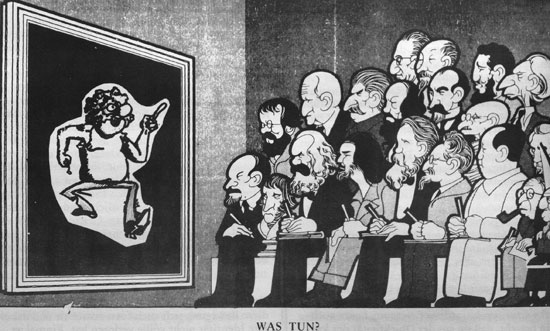

Image: This cartoon from Autonomie is based on João Abel Manta’s “A Difficult Problem,” 1975. Here, Manta’s map of Portugal is replaced with the Gilbert Shelton character Fat Freddy.