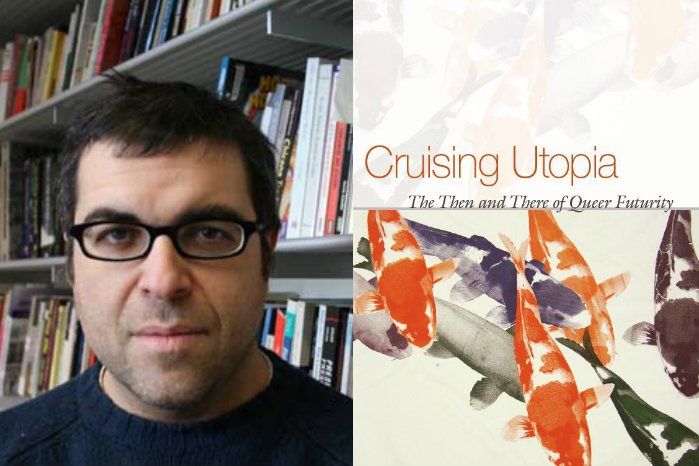

The journal Social Text has published an adapted version of Judith Butler’s José Esteban Muñoz Memorial Lecture, delivered at New York University in February of last year. Muñoz was an influential queer theorist who passed away prematurely in 2013, at the age of 46. His groundbreaking book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009) sent a jolt through both academic queer theory and activist circles. Bulter’s lecture seek to extend Muñoz’s work in this book, asking what key concepts like “disidentification” and “performative” might mean in a present-day context marked by a violent reassertion of white supremacist identity. Here’s an excerpt:

Let us return to Muñoz, or move forward with Muñoz, who is still sounding a call: “We must vacate the here and now for a then and there. Individual transports are insufficient.” It has to be a collec tive transport, and at times it seems we verge on science fiction: “The future is a spatial and temporal destination.” Muñoz tells us that sometimes we actively have to find the utopian, but at other times it comes at us, undeniable. We have to give way to its propulsion. It can carry us, but not alone; we must be willing to give way with others. This voluntary form of giving way or giving ourselves over is not something we can do on our own. In the first instance, it is feeling, but what is its source and range? Second, it is ecstasy, which is precisely a form of standing outside oneself that is also standing with another, and so makes unanswerable the question of whose ecstasy this is. Third, there is collective potential, which is neither a roadmap nor a plan but a way of breaking through the structure of inequality that allocates possibility differentially, deciding in advance whose lives will be possible and whose will not. Potential talks back to radical inequality; it opens up in an unlivable life the prospect of livability not so much as a fixed image of the future but as an open-ended time. This sense of expanse with an uncertain limit is not merely personal liberty but collective movement. Within the very conviction that this is not a life, some sense of living and feeling becomes unexpectedly communicable across communities on the margins or locked into minority status or held under siege and all too often defined by imprisonment and fatal abandonment. This pertains, as Tavia Nyong’o has written, to “an idea of affect as extensible in time and space, of affect as possessing a movement vocabulary and a set of principles for the navigation of a terrain.” The feeling does not precisely come from within: it follows from being moved; it passes over into and through the crowd—neither a fascist frenzy nor a loss of all defining difference, but an awkward, fractious movement that continues by moving and being moved.