by Abbe Schriber

To question everything. To remember what it has been forbidden even to mention. To come together telling our stories, to look afresh at, and then to describe for ourselves, the frescoes of the Ice Age, the nudes of “high art,” the Minoan seals and figurines, the moon-landscape embossed with the booted print of a male foot, the microscopic virus, the scarred and tortured body of the planet Earth. To do this kind of work takes a capacity for constant active presence, a naturalist’s attention to minute phenomena, for reading between the lines, watching closely for symbolic arrangements, decoding difficult and complex messages left for us by women of the past. It is work, in short, that is opposed by, and stands in opposition to, the entire twentieth century white male capitalist culture. How shall we ever make the work intelligent on our movement? I do not think the answer lies in trying to render feminism easy, popular, and instantly gratifying. To conjure with the passive culture and adapt to its rules is to degrade and deny the fullness of our meaning and intention.

—Adrienne Rich, Foreword to On Lies, Secrets and Silence

Among the goods for sale at the women’s social club The Wing are T-shirts, keychains, baseball caps, and tote bags, each of which bears a cheeky phrase in a range of energetic fonts: “Boys Beware”; “Girls Doing Whatever the Fuck They Want in 2017.” There is a pencil set, currently sold out, in a range of sorbet-hued pastels labeled with both fictional and real women, including Lisa Simpson, Michelle Obama, and Benazir Bhutto. There are shoelaces, shower caps, and stickers emblazoned with the company’s curved “W” emblem. The tone is sweet with a hint of toughness, enough to puncture the illusion of docile, meek, or worse: nice. Despite being an organization geared toward professionals, the swag belies an attachment to cutesiness; to girlhood. It’s not that girlishness and womanliness don’t coincide. Indeed they are inseparable. “Girl” has bypassed its association with traditional gender binaries—it is at once affectionate greeting, private vernacular code, queer appropriation, and stand-in for the innocence and safety that many women have had to create for themselves.1 However, these products, and their social-media visibility, perform a kind of oblique feminism, which declares itself not only through conspicuous consumption, but endless publicity and self-imaging. For The Wing, the complex identificatory process of “girl” is touted as a form of defiant subversion that remains a smoke-and-mirrors operation, given the upward mobility aspired to by its members.

Ostensibly, we should be cheered by the prospect of so many newly feminist-identified people in the public sphere. And yet, visualizing feminist power now frequently happens through branding, or worse, the conflation of consumption and activism. Contemporary for-profit feminisms want women to inhabit elite positions (akin to Sophia Amoruso’s famed “girlboss”), as well as glorify the hierarchical qualities of a “boss.” (Women spent decades entrenched in “pink-collar” jobs characterized by emotional labor, exuding comfort, nurture, tranquility, and assurance; it follows that a girlboss deploys practices of assertion and domination typically understood as leadership skills.) While these aspects of resurgent feminist strands have been critiqued, less has been said about the role of visual images, and of a feminist role in looking—how women use bourgeois class affinity and the promise of the upgrade to represent themselves, and sell that representation to other women. This might include everything from hip new members’-only community spaces like The Wing and Hey Sally, to interviews endorsing products used in a beauty routine, to meticulously lit salad blogs featuring arcane ingredients. Integral to this ubiquitous publicizing role is what Hito Steyerl has called “circulationism,” meaning not the actual production of images, but their state of constant malleability and mobility in postproduction: “the public relations of images across social networks,” she writes, and their “advertisement and alienation.”2 No image exists that isn’t selling something, even or especially if we didn’t know we wanted it. After all, where and how—and for whom—does current feminist labor become visualized, reproduced, and consumed? Given that emancipatory politics is now easily interchangeable with the desire to be seen championing a feminist cause, does feminism happen if nobody sees it?

Though The Wing is hardly alone in selling goods that declare feminist self-actualization, the company is among the first to monetize a women’s-only community, for which the merchandise recirculates as a lived advertisement. As is by now all too clear, “community” and “collectivity” are being rapidly absorbed by corporate brands along with words like “self-care,” “empowerment,” and even “patriarchy.” These terms get redeployed into the rhetoric of marketing, and help make consumers into entrepreneurs, celebrating leadership and self-determination. Currently, Lululemon, the lifestyle and fitness clothing brand, offers a “Sweat Collective” geared toward “leaders in sweat,” which “offer[s] special perks to our members as a thank you for their leadership and commitment to sweat.” The women-founded cosmetics brand Glossier defines itself as a “beauty movement that celebrates real girls, in real life,” even as it mediates this authenticity through the inherent artificiality of its products, and a femme, millennial-pink cyber-presence quite literally punctuated with rainbows.

On the one hand, these companies are using feminist strategies and language to elevate the commodity beyond a simple product, appropriating the language of personal choice—read: purchase—that now governs and regulates consumers. On the other hand, there is the content of the products, like the Benazir Bhutto pencils, which rapidly recycle internet slang and topical pop-culture phenomena into objects. “The Future is Female” went viral as an unofficial campaign slogan for Hillary Clinton in 2016, after being popularized and sold on apparel by the design studio and retail space Otherwild. The phrase, as the Washington Post reported, has its roots in second-wave radical feminism, once the slogan for the lesbian-founded New York bookstore Labyris. Rediscovered in a 1975 photograph reposted by the archival Instagram account @h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y, “The Future is Female” reentered political discourse after decades of obscurity with the permission and collaboration of the photograph’s maker. Is its resurgence in the material life of contemporary politics proof of a revitalized activist culture? Or is it the radical ideals and counterculture of the New Left 1960s and early 1970s, packaged and internalized into an individualist system that equates consumer goods and political interests? On a corner of Wythe Street in gentrified North Williamsburg, there is a store called Bulletin Broads, which brings women-run emerging brands to brick-and-mortar markets in an attempt to drive online consumers back to physical retail spaces. Upon entering the shop, one might choose to dip their credit card to give five dollars to Planned Parenthood, or sip rosé out of a paper cup. All of the wares are marketed to woman-identified shoppers—for example, small gold trophies depicting beauty queens and cheerleaders that say things like “Smasher of the Patriarchy,” tote bags that illustrate “nasty women,” pink t-shirts that read “Designer Pussy,” and faux-marble mugs made in China labeled with “Misogynist Tears.” There are chunky crystal rings, bright posters that pun on Frida Kahlo’s name, lighters covered in chain mail, Chinese slippers embroidered with words like “cute” and “kinky,” and jade rollers that stimulate bloodflow when used on the face. The influx of what, to some extent, can only be described as feminist kitsch, cannot be separated from the direness of our political context. Brands creating goods like these flourished during the trauma of the 2016 election and its surreal afterlife—and Bulletin Broads opened its Williamsburg space last November. It can be challenging to see how commodities of this sort elevate women as the very constituency to whom they are meant to appeal. Yet at the same time, feminist kitsch allows for self-recognition, claimed through the possibilities of consumer life in the public sphere when the responsibilities of citizenship seem not only daunting, but intensely disillusioning. In Instagrammable capitalist feminism, the difference between self-recognition and self-branding is increasingly blurry. If corporate and governmental strategies alike now utilize radical leftist slogans and vocabulary, consumers have internalized and redistributed the rhetoric of marketing in the types and frequency of our social-media posting, in our desire to be seen.

…

Let me be clear. The difficulty of this moment in commoditized feminist public life is that we want to be “hailed,” to be called by its name. It is hard to remain unseduced by the accoutrements of a chic communal belonging, by the promise of speaking back to patriarchy, by donating a portion of the proceeds to Planned Parenthood in the process. Furthermore, for black women and women of color, rerouting mass-media spaces as spaces of social recognition can be seen as tactics of survival, of self-preservation rather than indulgence, to paraphrase one of Audre Lorde’s oft-quoted lines. Conservation of the self corresponds to the maintenance of a (counter)public sphere. Lorde, Angela Y. Davis, bell hooks, Chandra Mohanty, and many other black and third-world feminists have led the struggle to think beyond a capitalist system that it is impossible to wholly escape. Their vocabularies of radical imagining have been crucial to equating mere survival as political resistance, reversing the forces of denial, erasure, blame, compromise, and death that weigh on poor, black, and/or queer people. At the same time, the affirmative language of these thinkers is most vulnerable to appropriation, as the verbal expressions and gestures of black women tend to be in the trend cycles upon which capitalism depends. Hence, all the more reason that sites of appearance, whether in advertising, consumer goods, or political representation, require contestation. Sara Ahmed writes:

Those who challenge power are often judged as promoting themselves, as putting themselves first, as self-promotional. And maybe: the judgment does find us somewhere. We might have to promote ourselves when we are not promoted by virtue of our membership of a group. We might have to become assertive just to appear. For others, you appear and you are attended to right away. A world is waiting for you to appear.3

As Ahmed points out, there will always be a space of appearance for those who have less to lose, and in a context of feminist representation, that pertains to white, heterosexual, female-identified feminists. But, as Krista Thompson has suggested, visibility as a primary ambition may need to be rethought, given that “those who continue to find themselves on the social and economic margins seem to demand visibility more than anything else,” which “points to the limited effectiveness of strategies of visibility—their failure to produce the political power they were supposed to assure and secure.”4

…

Perhaps none of this would seem as egregious if it weren’t under the auspices of a communal female empowerment that largely excludes those who might most benefit from it. In the case of The Wing, for whom is its visibility truly meant, when it financially benefits a small elite? For $215 a month or a $2250 annual subscription, there are many who will never have access to the self-professed “throne away from home”—the self-advancement, lifestyle upgrade, and networking potential that a membership promises. However, despite being founded as a physical space meant to foster real-life networks, it is The Wing’s so-called immaterial spaces—its digital connectivity and online community—which are the real heart of its operative functioning. Though a recent article in the Village Voice suggested that future membership might include sliding-scale options, the application process also, unsurprisingly, makes evident what is really sought in the Wing population—“influencers,” future members likely to post, like, and re-gram its panel discussions, roof-deck bar, or partnerships with brands like Chanel. In the brief web application, the final question requests a link to a social media account, which “helps us to get to know you as a person.” Therein lies the crux of The Wing’s own mission, and its goal for recruitment. An enterprise whose very existence depends on exclusivity, its search for members is predicated on the conflation of image and self, amid few other personal questions. Perhaps this analysis puts too much stock in the idea of a self before our own writing of it—of interiority that exists somehow outside or apart from its online expression. Perhaps it is my own naïveté that wants this to be true.

Social media—its instantaneity of access and gratification—stokes consumer desire and social status as much as it fosters networked activist consciousness. Now it helps market a feminism that is transgressive, or according to another trendy term, “unruly.” Visual economy has controlled and mediated the image of oppositional feminist subjectivity from the beginning, though. In the late 1920s, the president of the American Tobacco Company (ATC), George Hill, hired the public relations consultant Edward Bernays to counter societal taboos against women smoking in public, and convince female consumers to purchase more cigarettes. Bernays, widely credited with the founding of the modern public-relations industry, happened to be the nephew of one Sigmund Freud, who sent him a copy of General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. His uncle’s ideas helped Bernays modify propaganda from wartime purposes to the rise of mass consumption, and connect commodities to the unconscious, rather than appeal to the rational mind—facts, numbers—as many advertisers (and government officials) had tried to do. Bernays spoke to the psychoanalyst A. A. Brill to “figure out what cigarettes mean to women.”5 Brill told him that cigarettes were phallic symbols, and by making cigarettes signify opposition to male power, Bernays could convince women to buy them. He did just that in a carefully orchestrated stunt for the 1929 Easter Parade in New York, sponsored by Hill and the ATC. Bernays recruited women to march in the parade, and then at an arranged time, light up their cigarettes, which became referred to as “Torches of Freedom.” By tapping into the unconscious, irrational desire of women, the image of smoking—the originary signification of independence and subversion—set the stage for how images would mediate and control perceptions of feminist claims to power. In other words, by recuperating the phallus, the resignification of the cigarette parallels the pursuits of a “lean-in” feminism and the drive toward capitalist ambition and gender equity espoused by The Wing and Amoruso’s Girlboss Foundation, among others. The story of Bernays and the cigarette industry illustrates how the right to consume became linked to social visibility: the power of purchase would seem to bestow a more visible, if not more equal, citizenship. This anticipates a hallmark of neoliberal capitalist feminism: economic identification, embedded as it is in racial and gender subjectivity, as the foundation for political life.

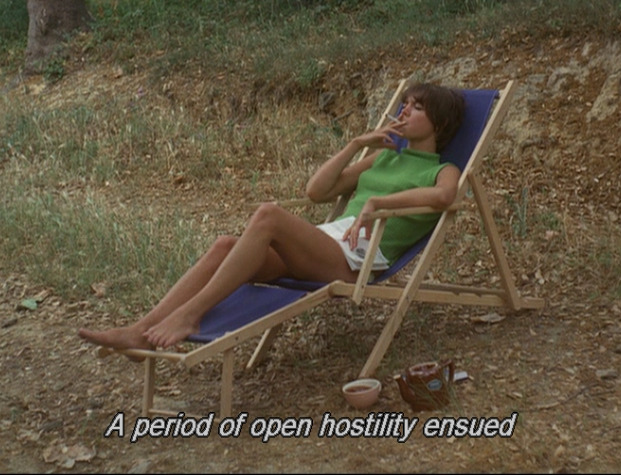

The notion of gender balance at all costs drives popular Instagram posts such as a found image, taken from Eric Rohmer’s 1967 film La Collectionneuse, posted to The Wing’s account on August 5 of this year. A woman (Haydée, in the film) wearing a light-green, sleeveless mock turtleneck leans back in a lounge chair, smoking a cigarette of course, a book propped open on her lap. Superimposed on top of the film still is the subtitle: “A period of open hostility ensued.” Combined with the meme’s caption—“When you realize only 4.2% of fortune 500 companies are run by women …”—this text helps recast a New Wave interpersonal drama as corporate plotting and scheming.

The Wing assumes that fusing female collectivity with work and social status—perhaps work as social status—is something at once attainable and necessary for women in order to participate in the organization. Such ideals continue to customize desire, envy, and wish-fulfillment; they operate under the guise of empowerment, yet inevitably depend on lack and exclusion. After all, 4.2 percent is still a percentage under the rubric of a 1 percent. In attempting to evade sexualized, idealized images in mass media, now many images for and by women trade on upwardly mobile status and the liberatory illusion of work, in the process fostering admiration and its easy flip side, envy. In a tour-de-force essay on Toni Morrison’s novel Sula and the stigma of competition amid female solidarity, Sianne Ngai shows the paradox of a capitalist society that is based on competitive markets, but that disapproves of women who are at odds—as in second-wave feminism’s repression of female competition. But envy, Ngai explains, is a negative or shameful emotion whose outcome is turned inward rather than outward, as in the dynamic “progress” of productive competition.6 Envy and admiration are closely related, and this is in part why admiration can at times produce ambivalence in the admired. This interconnected system of response is pivotal to how capitalist feminism links liberatory, collective identification to consumption and appearance. We can see it in the “relationship status” cartoon posted to the Instagram account of Spanx, in which a box next to “Building My Empire” is checked rather than the boxes next to “Single” and “Taken.”

…

On the occasion of the International Women’s Strike, a group of academics and theorists wrote a text for Viewpoint magazine in solidarity with a “feminism of the 99%” Writing in response to the Women’s March and other vast waves of resistance and disenchantment incited by Donald Trump’s election, the writers articulated the need to hold broader neoliberal institutions, of which Trump is merely symptomatic, to account:

Lean-in feminism and other variants of corporate feminism have failed the overwhelming majority of us, who do not have access to individual self-promotion and advancement and whose conditions of life can be improved only through policies that defend social reproduction, secure reproductive justice, and guarantee labor rights.

Among the signers of the Viewpoint text was Angela Y. Davis. As early as 1981, Davis had raised her suspicions of wage labor as a liberating force and key touchstone of women’s liberation. In “On the Approaching Obsolescence of Housework,” she argued that the conventional notion of a housewife who did not work for wages was one only available to white middle-class women. Not only had black women been conscripted into forced labor alongside black men under chattel slavery, but domestic work outside the home had long been monetized as the domain of black feminine labor. Left with few other options to support themselves and their families in the north and westward sweep of the Great Migration, black American women had effectively already been earning wages for housework, as one of the few jobs consistently available to them. Davis thus pushed back on the Wages for Housework movement of the 1970s supported by theorists like Silvia Federici, citing this history as well as the history of women’s paid domestic labor under South African apartheid. According to her, the oppressive situation of labor would remain essentially unchanged if women became compensated for housework. Further, wages would fail to alleviate the boredom, psychological alienation, and personal isolation that so often accompany the restriction of labor to the traditionally “private” sphere.

Davis foresaw the ways in which simply putting women into the positions of patriarchal authority would only continue cycles of inequality and worker oppression. How does that translate now, when women have become active agents in casting virtually any actions and activities as entrepreneurial? How does that translate now, when women’s collectives and other platforms for social visibility are at great pains to elevate women-of-color membership and participation—yet are ultimately curated according to the standards of a professional-managerial class, who contribute to the divesting of care work onto a labor class comprised mostly of low-income women of color?

We will not be escaping the throes of a consumer-driven feminism and its desirable face anytime soon. But we need a renewed critical eye that accounts for how feminism is coopted, and for who. Does a self-visualization exist that remains specific to the struggles of various women-identified histories, yet refuses spaces of appearance catered to traditional authoritative models? I find myself returning to Davis, to Ngai’s article on Sula, and to Adrienne Rich’s 1978 foreword to On Lies, Secrets, and Silence, a compendium that doesn’t offer any immediate answers, but helps articulate a pause, a challenge, a path toward a more ethical feminist mode of looking. Rich’s text feels something like a blueprint: registering the carefulness, the slowness of looking and communicating that allows for constant question-asking. Suspicion, in a constant state of surveillance and control, can manifest as oppressive weight, but maybe it could also be affirmation, creating skins of protection and safeguarding akin to what Ahmed suggests: unlearning inherited modes of consumption that define limiting conceptions of womanhood; questioning the drive toward visibility—toward being seen, and by who—that they underwrite.

×

NOTES

1 In using “women” I mean to signal anyone who identifies with, and as, this contingent, unstable term.

2 Hito Steyerl, “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?,” in Mass Effect: Art and the Internet in the Twenty-First Century, eds. Lauren Cornell and Ed Halter (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 445.

3 Sara Ahmed, “Selfcare as Warfare,” feminist killjoys, August 25, 2014 →.

4 Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 39.

5 Interview with Edward Bernays in Adam Curtis, The Century of the Self: Part I: “Happiness Machines,” BBC, originally broadcast April 29, 2002.

6 Sianne Ngai, “Competitiveness: From Sula to Tyra,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 34, no. 3–4 (Fall–Winter 2006): 107–39.

Image: Still from Eric Rohmer’s film La Collectionneuse.