Writing for the New Inquiry, Lavelle Porter reviews Dark Reflections by Samuel Delany, originally published in 2007 and recently reissued by Dover Books. The novel focuses on a black New York poet and the way his longing for recognition by a largely white literary world affects his self-conception as an artist and a black man. According to Porter, the novel examines a disturbing reality about race and literary awards: “For many people, these black artists, on that stage and on that list, are interlopers in a place where they are not supposed to be.” Read an excerpt from the review below, or the full text here.

Dark Reflections is a powerful novel about the writing life and its troubles. Rarely does one find a work that is so candid about the material realities of publishing, so bluntly honest about what it means to become a writer, a decision which Delany succinctly describes in his 2005 book About Writing as “the decision to enter a field where most of the news—most of the time—is bad.” The fact that Carroll and Graf, original publishers of Dark Reflections, went out of business in 2008 shortly after the novel was released in 2007, leaving the book out of print for eight years, adds a layer of irony to a novel about the precarity of publishing.

Delany has referred to Dark Reflections as a dramatization of the ideas presented in About Writing, in which he explains the function of what he calls “markers”: the awards, reviews, citations, and informal praise that accumulate in order to create and stabilize one’s literary reputation. “Basically,” he writes, “the problem of the writer’s reputation is, how, during your lifetime, do you generate as many and as effective literary markers as possible?” Delany pays attention to the absence and presence of those markers in Arnold Hawley’s life, and Arnold is painfully aware of how his work has been received by readers and critics. Arnold pays a steep price for literary ambition with a life of loneliness, poverty and insecurity. “The fact is, there is no praise as great as the praise I want,” Arnold admits to his therapist at one point.

It’s all too easy to say these awards don’t or shouldn’t matter, or that we (however one defines that “we”) should have our own awards. And certainly there’s always a place for the eccentric outsider artist who toils alone and rejects these structures entirely. But one of the more candid messages of Delany’s Dark Reflections is that the artist is not above such prizes, however big or small. These awards are part of the validating mechanisms by which the business of art gets made, where works of art get praised, contracted, and sold, and by which artists get access to funding and employment that allows them to produce more work.

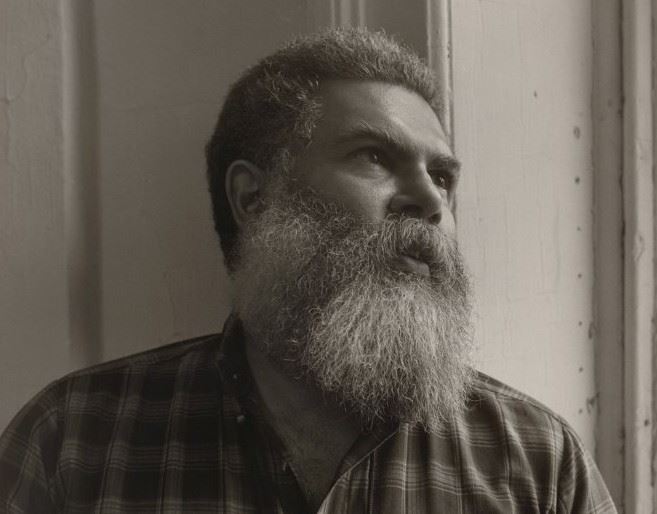

Image of Samuel Delany via blackkudos.tumblr.com.