The journal Religious Theory recently published a newly translated interview with Giorgio Agamben. The interview begins with a quote from Agamben’s book What is Philosophy in which he describes philosophy not as a discipline with a fixed essence, but rather “an intensity that can suddenly give life to any field: art, religion, economics, poetry, passion, love, even boredom.” Agamben goes on to talk about his intellectual and personal encounters with thinkers such as Foucault, Debord, Heidegger, Italo Calvino, and Elsa Morante. The interview was conducted by Italian journalist Antonio Gnolio and translated from the Italian by Ido Govrin. Read an excerpt below, or the full text here.

AG: In recent years you have intensified your call on “biopolitics.” Is this a concept we owe in large part to Michel Foucault?

GA: Certainly. But just as important to me was the problem of method in Foucault, namely the archeology. I’m convinced that these days the only way to access the present is through investigation of the past, the archeology. It should be made clear, as Foucault does, that archeological researches are not just the shadow that the interrogation of the present projects on the past. In my case, this shadow is often longer than that sought after by Foucault and probes fields such as theology and law, which Foucault hardly looked at. It certainly may turn out that the results of my research are disputed, but I hope at least that the purely archeological researches I developed in State of Exception, The Kingdom and the Glory, or in the book on oath, help us understand the time in which we live.

AG: Another thinker who helped us understand the time in which we live was Guy Debord with his book The Society of the Spectacle, a text that still helps us comprehend our present.

GA: I read it at the very year of its publication, in 1967. I became friends with Guy many years later, in the late ’80s. But I remember, in the moment of its first reading, as through our conversations, the sigh of relief seeing how his mind was absolutely free from the ideological prejudices that had compromised the fates of the movements. In ’68 and in the following years, the friends of the movements I visited proclaimed themselves, without fear or shame, and with an absolute abdication of the faculty of thinking, “Maoist,” “Trotskyist,” etc. Guy and I had arrived at the same lucidity; he from the tradition of the artistic avant-garde from which he came, myself from poetry and philosophy.

AG: Debord said about himself: “I’m not a philosopher, I’m a strategist.” In your opinion, what did he mean?

GA: Despite this affirmation you cite, I don’t think that for him there was any conflict between being a philosopher and a strategist. Philosophy always involves a problem of strategy since, even if it searches the eternal, it can do so only through a confrontation with its own time.

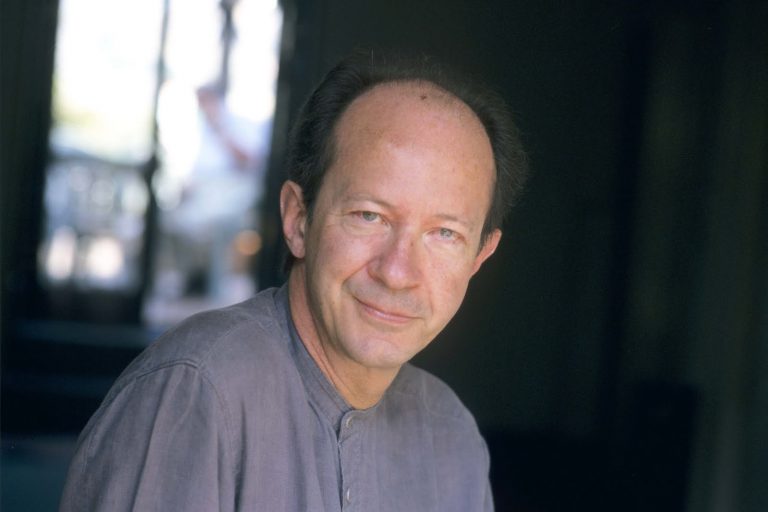

Image of Giorgio Agamben via Religious Theory.