For many years now Indian essayist and novelist Pankaj Mishra has been among the most astute critics of Western hegemony and liberal capitalism in the English language. Across books like From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia (2012) and Age of Anger: A History of the Present (2017), Mishra has examined how the West’s self-satisfied, paternalistic stance toward the rest of the world has provoked backlash and resistance, leading in part to the decline of Western dominance that we see today. In the Fall 2018 issue of the Boston Review, Mishra talks to Wajahat Ali about the appeal of authoritarianism, complacent intellectuals, and Indian democracy today. An excerpt:

WA: Speaking of Indian democracy, you have written that “the formal and proceduralist features of democracy—elections—have superseded their substantive aspect: strong, accountable, and fair-minded institutions and officials.” How can Indians engage the democratic process in a meaningful manner? If this is not possible, then is democracy the best solution for achieving political equality in India?

PM: The answer to the many problems, inadequacies, and dangers of democracy should never be less democracy. It is true that in many parts of the world, ordinary citizens feel disenfranchised by alliances between national politicians and global businessmen. Liberal democracy—with its subordination of such substantive matters as equality, freedom, and general welfare to procedural issues, its obsession with the holding of elections and the preservation of norms—has turned out to be the best way of concentrating and deepening oligarchic power. This is the main reason it has provoked such furiously emphatic rejections worldwide from voters who feel utterly deceived and powerless, who no longer believe that liberal democracy is superior to authoritarian rule.

Still, the answer is not less democracy, or authoritarian populism. We need more democracy in India and elsewhere—substantive democracy. It is a truism that democracy in its Western habitat struggled for a long time to concede equal rights to slaves, women, workers, and the colonized on the grounds that they were deficient in reason. The project of equality and freedom was also continuously undermined by the rise of a market economy and a bureaucratic state, which placed economic and political rationality above moral claims. In many ways democracy in its ideal form has been more clearly formulated in postcolonial nations, where it was attached from the very beginning to promises of equality, social and economic justice, and the welfare of the poor and underprivileged castes. We need to rebuild and reinstitutionalize this vision. We say we believe in democracy. But the urgent question, wherever we are, is what kind of democracy? One where wage slavery is the norm? Where politicians deploy the ample tools of demagoguery to get elected and then ignore ordinary voters? Or, instead, one in which power is not concentrated at the top and people feel themselves to be citizens as well as voters, able to participate in making decisions that affect their lives? The latter is obviously preferable, but it will be difficult to work our way to it. Political elites have used elections and parliaments as instruments of legitimacy; they exercise monopoly power in the media as well, and they will not give it up easily.

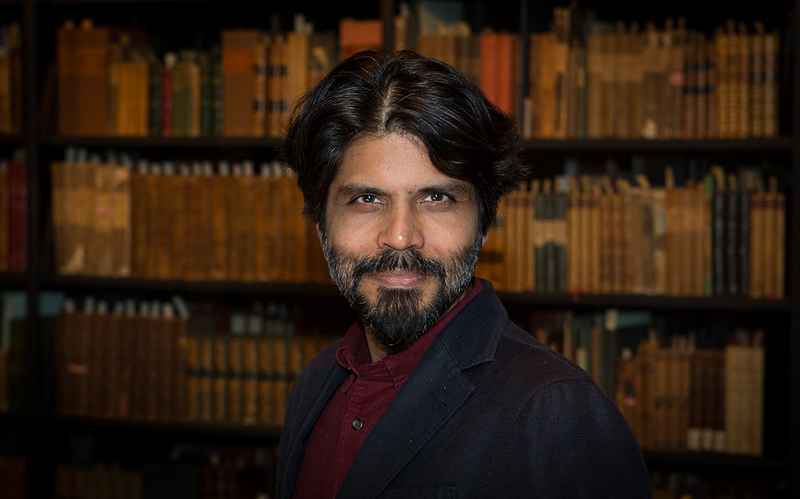

Image of Pankaj Mishra via his website.