In the June issue of Harper’s Magazine, Lidija Haas reviews two books on the pitfalls and possibilities of romantic loveon : Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating by Moira Weigel and Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table by Ellen Wayland-Smith. The former book argues that nearly every aspect of modern dating has become a form of work, while the latter investigates a historical attempt by a group of New England utopians to escape the constraints of traditional marriage. Haas praises Weigel’s sober dissection of dating’s drudgery, but wishes she spelled out what a modern utopian model of love might look like. Here’s an excerpt from the review:

It’s not news that all sorts of supposedly fun activities — going to the gym, playing video games, maintaining a social-media presence — have grown harder to distinguish from work. But dating, Weigel would have you understand, is among the worst. Its dissatisfactions are similar to those involved in many a job: a vast investment of time, effort, and emotion for inadequate reward; a lot of responsibility and not much power; and a setup that feels rigged against you. The physical demands aren’t negligible, either. New York dating, at least from the sidelines, looks taxing enough, but I hear that in California there’s such a thing as a running date, where, presumably, instead of grabbing a drink or a coffee, you throw on your spandex and sweat until the best man wins.

Dating feels like work, Weigel tells us, because it is and always has been. She traces its beginnings to the late nineteenth century. In chapters loosely organized around themes (“Tricks,” “Likes,” “Niches”), she moves through the frantic, competitive dating of Twenties and Thirties co-eds, the more stable pairings of the Forties and Fifties, and on into the fractured present. The book’s early pages describe women indoors: the girls who sat with their parents, waiting for their suitors to call; the sex workers who received clients one by one, like “artisans” or “small-business owners.” As the century turned, more unmarried women joined those flooding into the cities in search of work. There, dating meant a free dinner for women who couldn’t afford to buy one, or free entry into night spots that required a male escort. Brothels and red-light districts sprang up, and even those “public women” who weren’t charging — “charity cunts” was one of the more colorful names given to them — sometimes risked arrest. Compared with the older tradition of home visits, going out offered both greater personal freedom and greater social mobility: shop assistants and stenographers could marry their customers and bosses; an heiress could marry a popular songwriter (in this case, Irving Berlin). All kinds of couples could escape family surveillance; out of the parlors and into the parks, they found a certain privacy in public. Reading Weigel on this period, I was reminded of the feedback left by one young man after a 1939 preview of Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka: “Great picture . . . I laughed so hard, I peed in my girlfriend’s hand!”

Weigel attributes the rise of “going steady” — “all of the worst features of marriage and none of its advantages,” as Dorothy Dix wrote — in part to a shortage of men during World War II but mainly to a surfeit of cash after the troops returned. Many teenagers now had what would have been the “disposable income of an average family” only a few years earlier. “By the 1950s,” Weigel writes, “shopping had become the go-to metaphor” for dating, a comparison that she sees as symptomatic of a deeper link between the two phenomena. She herself has a soft spot for such language, describing the postwar period as one of “romantic full employment” or musing, “Does every year of hooking up simply put us in the emotional equivalent of more student debt?”

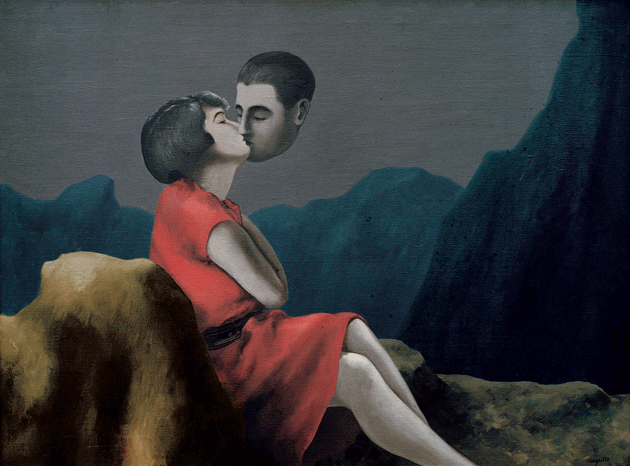

Image: René Magritte’s The Lovers. Via Harper’s.