We had a full house Sunday to launch the second and final issue of Architecture as Intangible Infrastructure, edited by Nikolaus Hirsch. In his opening comments, Hirsch noted that the classic toolbox architects have somehow doesn’t fit us anymore. This was the idea behind inviting the contributors for this issue of the journal. How have new technologies like AirBnB changed the landscape of architecture?

Beatriz Colomina

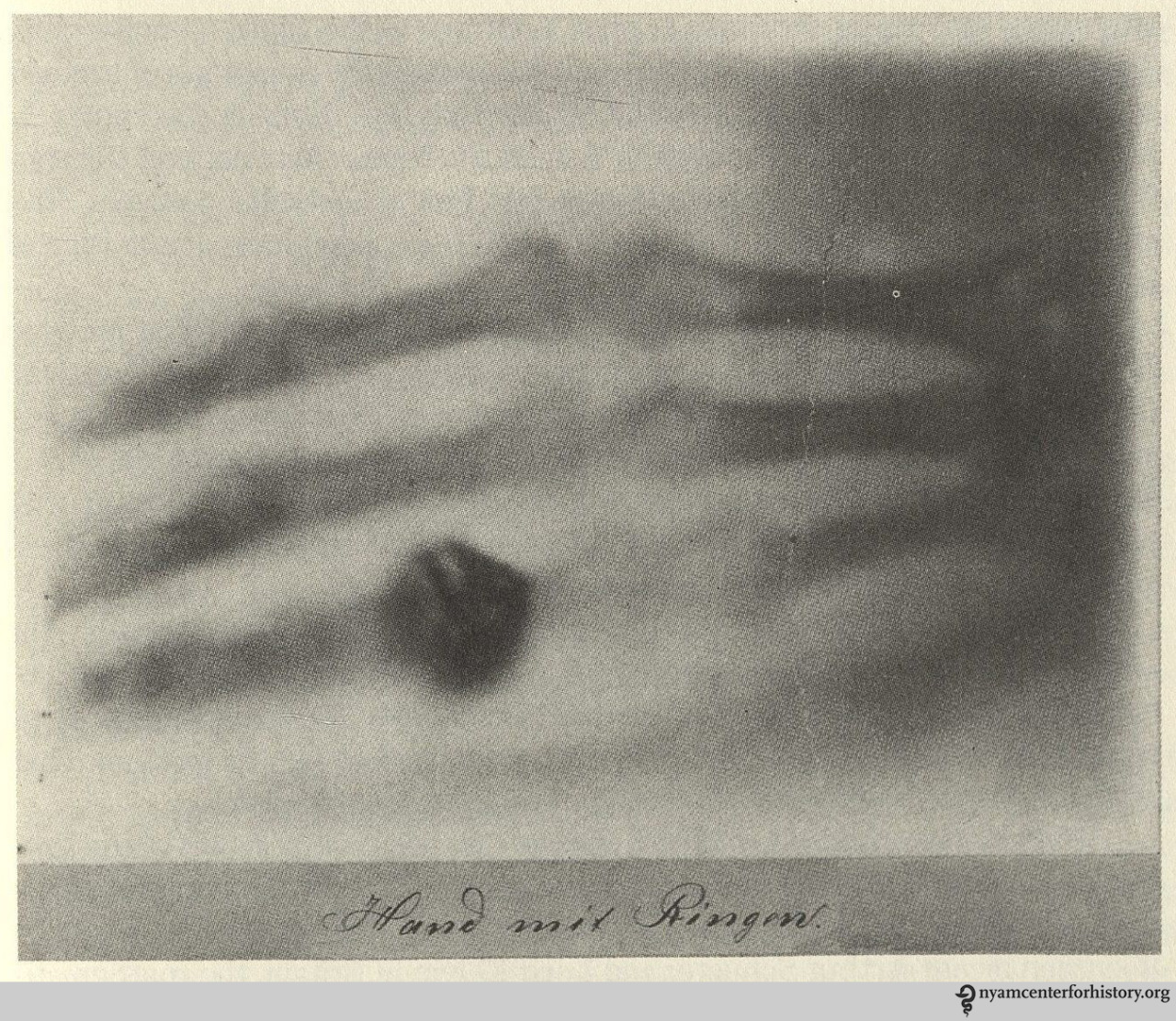

The x-ray of Anna Röntgen’s hand

First up is Beatriz Colomina. She speaks about x-rays, and the splash they made when they were debuted in the late 19th century after being discovered by William Röntgen. Predictably, reactions amid the invention of the x-ray were mixed, and even suspicious. One headline includes “THE LIGHT THAT NEVER WAS: A Photographic Discovery Which Seems Almost Uncanny.” Anna Bertha Röntgen, the wife of discoverer William Röntgen, said upon seeing an x-ray of her hand, witnessing her bones, “I have seen my own death.” The idea that an x-ray can see through your clothing (i.e. at airport security), has been there since the very beginning, says Colomina.

Edison exhibited x-rays to the public in 1896, after which they became a bit of a fair spectacle—you could get your x-ray taken in public at these fairs as a souvenir. They were used by the police (there’s a famous image of a woman hiding a bottle of liquor under her clothes), as well as in the entertainment industry in many forms, notably in slot machines in Las Vegas (anyone know how this would work?!); and of course in medicine—x-rays are known as the “medication for tuberculosis.”

In a comment after Colomina’s talk, e-flux journal editor Brian Kuan Wood noted that transparency is used as both sickness as cure; when we’re referring to surveillance it’s a sickness, whereas in tuberculosis it’s a cure. He mentions Philip Johnson’s Glass House, its uncanny embodiment of erosions of privacy and complete transparency; making visible what is normally obscured.

Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon installation view at Fondation Louis Vuitton

Artist Taryn Simon spoke with Nikolaus Hirsch about her exhibition at the new Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, the building for which is a rather ostentatious design by Frank Gehry. (See the e-flux conversations topic about this building, which inspired curator Maria Lind to organize a guest discussion about the function of art in dwarfing, formidable buildings such as this.) In the vein of institutional critique, her exhibition “excavates” the history of the five-year construction of the building itself, presenting stories relating to worker suicides, anti-bourgeois graffiti, etc. “You can imagine [the workers] pushing up against all of this privilege from behind,” says Simon, “and I’m always interested in this sort of silencing.”

From her website:

In A Polite Fiction (2014), Taryn Simon maps, excavates, and records the gestures that became entombed beneath – and within – the building’s surfaces during its five-year construction. Designed by Frank Gehry, the Fondation was built to house the art collection of Bernard Arnault, one of the world’s wealthiest individuals and owner of the largest luxury conglomerate in the world. Simon collects this buried history and examines the latent social, political, and economic forces pushing against power and privilege.

Systematically chronicling four hundred interventions enacted in the building’s cavities by plasterers, scaffolders, engineers, masons, electricians, security guards, draftsmen, tile setters, interns, supervisors, and others, Simon documents discoveries that include a pack of Marlboro Lights with one cigarette left for a future smoke, concealed behind drywall in a service stairwell; a newspaper article about the 2013 murder of three Kurdish political activists in Paris, placed in the ceiling of the executive office; and a plastic bottle of urine hidden behind ceramic tile in the administrative restrooms. These markings have now been deleted by the polished surfaces of the museum. A Polite Fiction probes the liminal space where voices are both quieted and preserved. Simon’s collection also investigates the removal or disappearance of objects from the Fondation. Simon entered an invisible marketplace, tracking, purchasing, and photographing objects taken from the site. Items include copper and aluminum cables sold to scrap dealers; cement used by a father to build the walls of his daughter’s bedroom; and an oak sapling that a worker took to Poland, planted, and named after his boss. The custody and movement of these objects transform their value, as they pass from employer to worker and, ultimately, to artist.

Kadambari Baxi from Who Builds Your Architecture?

Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Along with a reinvention notion of architecture as it relates to technology, Baxi reminds us that we need to rethink the relationship of the architect and the worker in a neoliberal society. Today, the architect is almost completely removed from the nuts-and-bolts construction of buildings, which often gives way to exploitation of workers. What is the ethical imperative of architects to make sure that their buildings are ethically built by non-exploited workers who themselves have sustainable, ethical shelter? We’re seeing a crisis now in the Gulf, where many migrant workers die and their deaths aren’t very publicized. This brings to mind Oleksiy Radynski’s 2012 video “Barracks for workers of Olimpiyskiy Stadium in Kyiv.”

From their e-flux journal article:

In our recent exhibition at the Istanbul Design Biennale, WBYA? (Who Builds Your Architecture?) installed a “workroom” that allowed visitors to reflect upon the context of transnational building projects and to consider where human rights issues overlap with processes of architectural design and construction. On a large table built for holding discussions and for reading reports on various issues, we displayed a long drawing that mapped the network of a fictional building project. A stadium construction site sat in the center of the drawing, and both sides charted the paths of migrant construction workers as they travel from their villages to job sites as well the movement of a steel truss from design to fabrication to a building site.

In the drawing, a steel truss is designed by architects based on the overall stadium design, aesthetics, and functional criteria. Most likely, aspects of labor required for the truss to be fabricated or installed on site are not considered for its design. Architects use BIM (Building Information Modeling) and other software to design and coordinate construction details with engineers and manufacturers. For large international building projects, architects often collaborate with specialized consultants such as structural and mechanical engineers, fabricators, and sustainability consultants who are often from different countries, atomizing knowledge of the building construction across a wide spectrum of experts. Factories may not be located in the same countries as architects and engineers, clients or the site of the building project. Architects and consultants may visit the factory to review a prototype or mockup of the truss. Production line workers at the factory may or may not be unionized, or work with fair labor practices. A crew of port workers including handlers, train operators, drivers load and unload the containers in different countries, and those containers must clear custom review and pay requisite national tariffs. Finally, the steel truss arrives at the staging area of the construction site, where the site foreman, subcontractors, and construction managers oversee the installation of the truss in the building by migrant construction workers, possibly referring back to architects’ construction drawings.

We interspersed this mapping of the convergence of global workforces on a building site with reports from sources such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International that document the issues facing migrant construction workers. Descriptions of steps in the migratory paths of workers as well as working processes in design and construction processes ended with questions speculating where solutions might intervene. How can architects ensure human rights protections extend to those who build architecture worldwide? How can organizational charts be reconfigured to link complex global interdependencies? How can technologies facilitate new relationships between architects, design consultants, and migrant workers who construct buildings? How can architects advocate for better working and living conditions on building sites around the world?

The project team for WBYA? exhibition included Laura Diamond Dixit, Tiffany Rattray, and Lindsey Lee.

—Kadambari Baxi, Jordan Carver, Mabel O. Wilson

Jorge Otero-Pailos

The apergon of the Propylaea at the Acropolis protected the stones during transport and construction and was meant to be struck from the work in a future that has yet to come. Photo: Jorge Otero-Pailos

Jorge Otero-Pailos presented on the idea of monumentaries and the “apergon.” Monumentaries are composites; ancient monuments with contemporary buttresses that defy our expectations of what architecture is; we’re used to architecture being something that holds together aesthetically. Here, buildings can be pieces that are not necessarily pulled together aesthetically for a multitude of reasons, oftentimes aesthetic and legal. These legalities vary from country to country. In Venice, Italy, for example, anything added to an ancient monument is supposed to bear the mark of the contemporary; it isn’t supposed to pastiche the time period in an attempt to aesthetically “fit in.” The first to speak about the architectural supplement is Kant, who refers it to an “apergon.” It is something that is removable, but something without it cannot exist. The supplement in preservation is meant to protect the work, which is something different. A prime example of this is the Acropolis, which is buttressed by a gigantic steel bar.

“The cloud over Gaza that day is the meta-data.”

Eyal Weizman speaks bout aerial wartime photographs and how one can gather much information from analyzing their cloud forms. Even on a practical level, ambulances drive toward plumes of smoke when communication networks break down. We use architecture here as clouds, as the geology of the air. The architecture of the whole city becomes an optical device to see images.