Writing in The Atlantic, Vann R. Newkirk II has an eloquent and moving account of his visit to the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, which recently opened in Washington, D.C. The museum is a project of the Smithsonian, which is essentially the national museum department of the US government. So perhaps surprisingly, writes Newkirk II, the museum provides an unsparing and thorough look at the brutalities visited on African Americans throughout their history, and at the efforts to deny and bury that history. Here’s an excerpt from the piece:

The underground placement of the history exhibit is probably better described as a purposefully subversive use of space, rather than relegation. After an initial walk down a stairwell framed by a mural of the triumphs of black history—the photos of Muhammad Ali and Barack Obama and Martin Luther King, Jr. that most people expect—viewers are essentially deposited into the bowels of the slave ships that stole so many souls from the African coasts. Hushed, claustrophobic halls display the worst of the bloody origins of slavery and detail how the slaves who were lucky—or unlucky—enough to survive the trip below the decks could only expect to live an average of seven years after being sold into plantations.

The resulting climb up through history is a barrage of information and an assault on the senses, an intentional juxtaposition of promise with sorrow. At one point, after walking past a proud depiction of a black Revolutionary Patriot, viewers encounter an huge multi-story exhibit embossed with the most famous words of the Declaration of Independence: All men are created equal. Standing underneath those words like Damocles under his sword is a statue of the framer Thomas Jefferson. Beside him is a pile of bricks representing the Monticello, with each brick representing one enslaved human that built it.

The descent and ascent achieve an effect similar to Dante’s harrowing journey in Inferno, and the walk upwards through Reconstruction, Redemption, the civil-rights movement, and into the present day is a reminder of the constant push and pull of horror and protest. Black towns that don’t exist anymore and black neighborhoods that were burned down are memorialized alongside the works of Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. DuBois. One exhibit features the names of lynching victims, a soul-rending litany that feels even more awful because of the names themselves. How many freedmen renamed themselves as Freemans or after Founding Fathers in aspiration only to be killed? At least a few George Washingtons show up on the list.

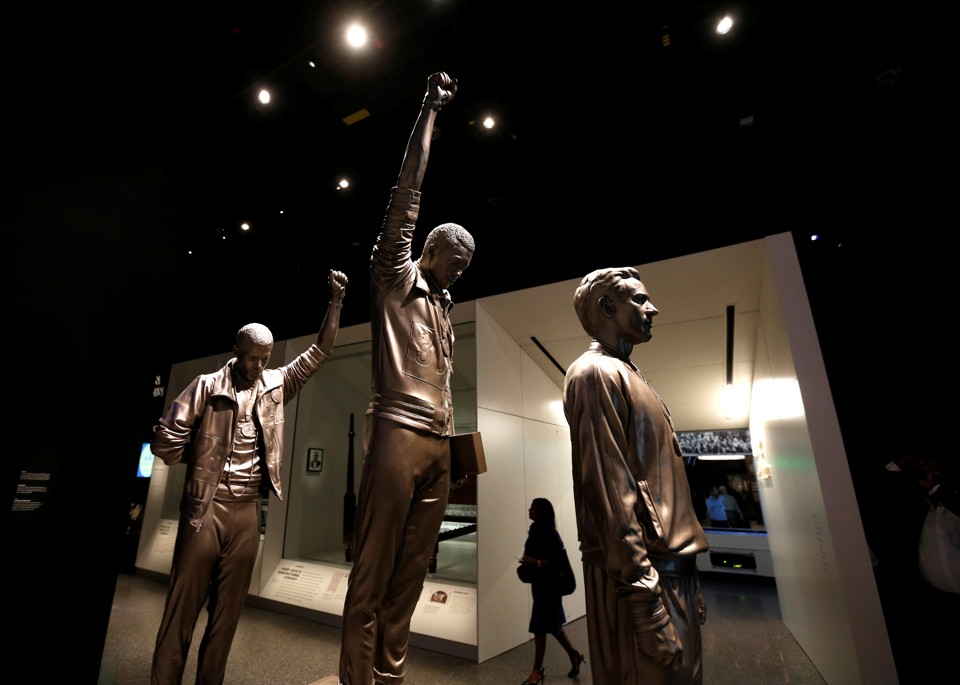

Image: A woman passes a display depicting the Mexico Olympic protest at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Via The Atlantic.