Tripoli Cancelled (2015). Production image: Dimitris Parthimos.

It was the end of the opening week of documenta 14, most visitors had already returned home, but we were still there. “Returned home”—well, my situation is changing rapidly.

It was also Easter, so Athens itself was quiet. We met, appropriately, on my way to the airport; I was about to return to Istanbul, briefly, and he would return to New York the following day.

We talked about building connections to place—for short or long periods. To deliver a talk, to shoot a film, to stay for open-ended time. Will this relationship with place remain, or fade? One could also build relationships that embrace the temporary, you know; memorial photos, scarf exchanges, etc. So we met on my way to the airport to talk about places and displacement in relation to his film, Tripoli Cancelled.

—Didem Pekün

Didem: I’m so glad that we managed to meet before I left. I want to talk to you about Tripoli Cancelled. And how I am haunted by it. I mean, in a sense, the film, for me, was all about a haunted space, not a physically but a psychically haunted space, about an in-between stage, about not being able to move forwards, not knowing when this period we’re in the middle of will end. A radical instability. And, of course, inevitably, I want to talk about your film in relation to the question of displacement.

You know how I located your film in the museum, EMST? I was walking around and as I was looking at another installation, I heard a piece of music, calling me into a space—I entered the space and found myself in an airport, in a long tracking shot of a man exiting its doors and walking down and looking out at a very derelict space—the sound, the color palette … I mean that tracking shot with the music sat me down.

Tripoli Cancelled, EMST. Installation image: Mathias Völzke.

Naeem: We were in an in-between space ourselves. The airport is remote even from the last train stop (also called Ellinikon). After the first day, we understood that going outside for a lunch break would eat away two plus hours. So from the next day, we would arrive at 6:00 a.m., with food, and never see another human until evening when we left. The security guards trusted our Greek producer Maria-Thalia Carras, and concluded that we were well behaved and did not need to be guarded. So, nothing but us, a group of seven or eight; we were in our own absent space that whole time. A building, an empty runway, and the mountains in the distance.

Shooting Tripoli Cancelled. Production image: Dimitris Parthimos.

Didem: Time—the concept of time—is suspended in the film, or very stretched. Which is kind of also the case in any process of exile. One loses the connection to time as one tries to keep track of home and also live in a new adopted home. Then during that adaptation process, everything feels a bit surreal. As in the film …

Tripoli Cancelled opens a space different from our usual speed and rhythm to think through something that otherwise gets lost in newspeak through extreme long shots, awfully long periods of waiting, in an abandoned airport … And whatever was missing in that storyline was also somewhat translated through the inclusion of that very minimal, quirky music.

You basically put onscreen the psychology of that suspension and transition.

Naeem: Suspended time, starkly different from other projects I have worked on. There’s an abrupt staccato beat to the way Afsan’s diary enters in Afsan’s Long Day (2014). If you wanted to be schematic, your mind may reject the transition from Germany to Libya to Bangladesh. And maybe it should; it was a brutal collage, not a calm transition. Some audiences disliked the bombing scene in that one; the abrupt, very loud music. In Tripoli, the pace of easing from one scene to the next is as slow as I could make it, slower even. Petros, our cinematographer, would look over at me, waiting for me to say cut, and I would stare back and wait, always a few extra beats. I said earlier that we were in a dream state inside that building. I think we did not want to leave, so everything was elongated.

You have time to think of the frame, the space above his head, what he’s doing with his hands, his posture, why his suit doesn’t get filthy.

Didem: Yes, absolutely. It is “a dream within a dream.” Like the scene where he just folds his jacket, ever so neatly clears the space in that space. What do you call that space where the suitcases arrive in the airport?

Naeem: Baggage carousel. A site of much waiting in real life, for all of us. I remember fondly Emily Jacir’s piece from 2005, Embrace—a circular baggage carousel, a trip to nowhere.

Emily Jacir, Embrace (2005). Image: Alexander and Bonin.

Didem: Right, and then not only is a major transport space like an airport vacated or abandoned, but there is also a dual sense of politics in that a man is stuck there, in a liminal space.

That eerie disjunction is what makes the viewer confront the main questions: Why is this man devoid of all the things that make him a subject, i.e., a people, a destination, a bed, a home? Why is this man there?

Naeem: A human in a space vacated of purpose, detached from the grid of “productivity.” A lattice of nodes is always defined by usefulness. Suddenly, when the use value is silenced, one morning the lights flash a few times and then they go out. Slowly and quickly, people start leaving.

Didem: And then, why is the airport abandoned? Why are we listening to him reading his diary? But then there is an element of “weirdness” in the film as well, which brings together two or more things which do not belong together, as Mark Fisher writes: “The feeling of wrongness associated with the weird—the conviction that this does not belong.”1 So then, one is inclined to ask: why is he making an espresso with a kerosene heater in the middle of an abandoned airport?

Naeem: Not his diary, he is writing a daily letter to his wife. And he posts it too. I don’t know where he would find a post office in that airport, but he does.

Or maybe I think he does. Have you ever looked for a mail box in an airport?

Didem: Of course he is writing letters to his wife! I don’t know why I keep calling them diaries. Maybe because of day numbers and week names …

And then there is the book.

Naeem: He reads Watership Down, his son’s favorite book—which he has left behind as a survival gift for his father.

My father reads a lot, but he likes to change books. I could not imagine a more tedious space for a man like him than to be doomed to reading one book. Thankfully, there are stories inside that one fable, starting with El-Ahrairah—a name that reminds us that outside is peril. A name of a protector derived from Elil (enemies), Hrair (thousand), and Rah (prince).

The prince with a thousand enemies.

Didem: There is also a line addressed directly to his wife that stayed with me:

I heard stories that, at the borders, they are separating families. Putting the men in cages, and then going home to a warm meal served by dutiful wives … We are the lines of control. They decide who is drowned and who is saved. But I know that if ever I was cruel, you would not sit quietly.

Also, I can’t help but think of Paul Ricœur with this film. He has a lecture called “Who is the Subject of Rights?” in which he writes of the four basic factors for the human agent to designate herself as a self-respecting and self-esteeming individual, thus as what he calls a capable subject. These four things are her capacities for designating herself as a speaking subject; being the author of her actions; being able to be the author of a narrative, a history (for instance uninterrupted by a forced migration); and finally, we esteem and respect ourselves when we can own our words, our actions, be the narrators of the stories that we tell about ourselves and evaluate them as either good or obligatory (to someone, to a group)—our ethical capacity.

But here is where it gets interesting: the conditions where the subject can exercise those rights. And I think it is here that the political potential of subjectivity lies, and where your film is so urgent, because, where are those people, and what is that space or institution where we can be in relation to others?

Because only when we exercise those modes do we become capable subjects, do “we become real powers to which correspond real rights.”2

Naeem: This witnessing is for the self, first; the intended addressee does not exist. If there is no post office in an airport, and no witness to the exercise, why continue a daily letter-writing regimen? Over a ten-year period? Why also bother lying to your loved one? She cannot even see.

Didem: Right, and your man in the film is all alone, he may be devoid of all those rights, but still, is he a prisoner, or the king of his domain? It is unclear, and that lends itself to the idea of agency in the eerie—that awkward situation opens a space for the new to emerge …

The space, thus the eerie, looks unsafe, but as Fisher notes: “The dream we’re in is not very safe either.”3

Naeem: Is “here” a time or a place? If you follow the publication period of Hannah Arendt’s report and subsequent book on the trials, having her as a dinner guest (as the man remembers) would place him in the 1960s. But there is a song he dances to which is from the 1970s.

There are two more phrases here that come from elsewhere: “Lines of control” from the LoC that divides Indian- and Pakistani-controlled parts of Jammu and Kashmir, the de facto (but not legal) border since the 1972 Simla Agreement. “Drowned and who is saved” comes from Primo Levi (also the source of “Der Muselmanner” via Agamben)—from one of his two books on surviving Auschwitz, The Drowned and the Saved (I sommersi e i salvati).

Tripoli Cancelled, EMST. Installation image: Didem Pekün.

Didem: Lately we have had to learn, again, the different definitions of this state—there is a hierarchy to exile, being a migrant, an immigrant, a refugee, you know. And of course, there is a hierarchy to the nationalities seeking refuge … Which is something Arendt also writes about in her text “We Refugees,” which begins with the first line: “In the first place, we don’t like to be called ‘refugees.’”

In one of his letters, the man says: “I heard more refugees arrived today. More and more. Burmese claiming to be Bangladeshi. Turks claiming to be Polish. Everyone claiming to be me.”

Naeem: Yes, that part spills out of a less well-known news report. The Rohingya Muslims are persecuted in Myanmar (part of the great land grab of this Malthusian nightmare epoch), even more intensely under the regime of Nobel laureate Aung Saan Su Kyi (one of the areas of disappointment for former supporters). The only place that they can escape to is neighboring Bangladesh, where they try to get passports so they can migrate elsewhere. One theory is that biometric smart card IDs were instituted partially to stop this.

The “Turks pretending to be Polish” is a fiction about how people could try to enter the EU. It’s not based on any news event. But as the Polish were reviled in the UK during the Brexit vote as “stealing the jobs” (something that even resonated with older British Asians, as Shumon Basar recently reminded me), I thought it would be interesting to think of who would be lower in that hierarchy. A hierarchy of passports, longevity in country, and access. And this changes all the time. Until 1978, Bangladeshis did not need visas to enter several countries in Europe. Also, what professions people go into—as George Simmel observed, the trader is always a stranger.

But I was also after much more than commenting on migration; I hope that does not get lost. The press coverage of the film has been predominantly about this aspect, even though that dialogue is only one minute in the film. It is perhaps easy shorthand that suits deadlines.

Didem: No, that’s what we’re talking about here, exile with all its extensions; time and suspension and limbo and, somewhat, adaptation. Because he also normalizes living there … There was a great calmness in the midst of this calamity in the film, except occasional emotional outbursts …

For instance, the moment when he sits in the helicopter, pretending to drive it. That moment of borderline delirium when one is so alone. That sense of hopelessness. It is actually very real in that very bizarre setting. Which reminds me of this line from your film:

In Auschwitz-Birkenau, to become Der Muselman was the sign of surrender, of a prisoner who has given up. In the other camps, other words were invented. In Majdanek, it was “Gammeln,” or rotting from inside. In Stutthof, they were “Kruppel,” or cripple. The space between being human and not. Less than.

Naeem: I first read about Der Muselmanner in Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz. It was after 2001, and many people were talking about the idea of “bare life.” And then Christopher Myers, an artist working with the spatial realization of black histories, lent me his copy of the book. I think Chris had wanted me to read another part, but the chapter on “Der Muselmanner” jumped out. Agamben is analyzing, among other things, references from Primo Levi’s memoir. The book argues that the term came about because the defeated Jewish prisoners could not even stand up. Their crouched pose was seen as similar to the Muslim prayer form. Other explanations have noted that it was a reference to the Muslim concept of “submission” and “surrender,” placing the term on an ontological rather than bodily level. I feel that the not being able to stand up/crouching down/falling down physiology is the more accurate root of the term. But this explanation is uncomfortable, as it suggests “Muselmanner” was an insult. I read this book back in 2004, and then sat on it. I could not think of how to discuss it. It seemed too enormously damaging a story, related as it is to a relationship that is already fraught due to post-1945 realities.

In the film, the term appears in one of his letters, and also in the dialogue at the bar, connecting to 1938. There’s a circular link back to Norman Gershman’s book Besa, as well as earlier research done by Mas’ood Cajee and others.

Didem: But you reference a different book at the end of the film.

Naeem: I cite the book Reflections from the Gas Chamber’s Waiting Room: The Memories of a Muselmann (Refleksje z poczekalni do gazu. Ze wspomnien muzulmana). A Polish memoir, never translated. I used that in the credits because it has the phrase directly in the title, which neither Agamben nor Levi have.

After I mentioned that this book was not translated, Adam [Szymczyk] tracked down a copy in Poland, and then translated a portion for me. This is from his notes about the book:

In the opening chapter, a definition of Muselmann is quoted (after an article by Jan Olbrycht, “Health Issues at Auschwitz Concentration Camp,” published in a Polish medical journal in 1962). This definition contains an ambiguity or logical loop that makes it perfectly not explain why the term Muslim (in Polish Muzulmanin = the German Muselmann) was transformed into a common name for a person in a state of complete physical exhaustion caused by starvation and other damage to the body and soul in the camp (such as ulcers, scabies, infections caused by lice bites, etc.). The name Muselmann seems to be related to a condition of detachment, delayed perception, and unresponsiveness caused by extreme exhaustion—therefore Muselmanns in camps were habitually accused of and punished for practicing what was imagined as their “passive resistance.” Which is Gandhi. So it seems that the name Muselmann is a conflation of the figure of the Other and someone practicing askesis (for instance by refusing to eat or even speak), an “oriental” figure in fact.

Didem: “These days, I find myself thinking a lot about Dojjal. The one-eyed demon who would lead humanity to the brink of extinction. And then the sun would come closer, and the earth would melt into itself.”

Dojjal seems to be everywhere now, as was predicted …

Naeem: The point of underscoring the Judeo-Christian-Muslim commonality of the idea of the anti-redeemer is that it is everywhere; there’s no localizing of this presence of an anti-historical (or maybe that is exactly the way history was written to be) tendency toward separation, dissolution, hate, violence. There is no guaranteed safe space; no refuge. So, whether it is an adopted or original home (which is which?), there will be no crossing into utopia. Each of us has to try to build portions of that calm we seek, wherever we are. And we have to build it with others, never alone.

documenta 14 artists, curators, and team onstage at Megaron, the Athens Concert Hall, preparing to perform Jani Christou’s Epicycle sound piece as part of inauguration press conference. Photo: documenta 14.

Didem: We’re running out of time! I can talk with you about these things endlessly—the question of location at a moment of thrice displacement for us both. We should have met weeks earlier since we’ve both been here for some time …

Naeem: In Athens, there were a number of South Asian artists, and a generational moment. Not only Amar Kanwar (who has been in four consecutive documentas), but also Nilima Sheikh and Lala Rukh. Gulam Mohammad Sheikh was also here, and he taught the prior generation in Bangladesh (people like Shishir Bhattacharya, who is now a senior professor at Dhaka University Charukala). Gauri Gill, Nikhil Chopra, and curator Natasha Ginwala. Because of visa regimes, it’s not always easy for midnight’s three orphans to cross over into each other’s countries (I have been in two conferences in Bangladesh where the Pakistanis were refused visas, for the usual absurd and surreal reasons of “insult to history”). And then the Greek film crew,4 we had our own time and meals together. I went back to Ellinikon to visit the Olympic Airways museum team. Being able to reconnect was needed, but it did mean we saw less of other people.

Didem: It’s funny how that happened — we had a dinner with artists and writers and curators from Turkey. I first thought, while sitting at the table, we’re here, why not meet with international friends whom we don’t get the chance to often meet as could easily meet in Istanbul? But then I realized — as all of us did — that we may not have this chance for a long time to come, since many of us are either in the process of leaving, or have already left Turkey. It’s on this particular occasion of documenta 14 taking place in Athens, in the south (Athens being so near our home), that we got together.

Which brings me, of course, to the fact that d14 was in Athens. And of course, relatedly, all work is embedded in and guided by the context within which it is produced and exhibited, which is precisely why you and I are sitting here and talking about these issues here and now. But of course there are many gaps, omissions; we could always ask for more.

I actually want to say some things here about what d14 and the south did for me, and for some other “southern” artists, with the risk of sounding like a naïve optimist, but then again, I’d rather be a naïve optimist then a cynical pessimist …

Naeem: I want to draw a distinction between some of the Greek critiques, which I read carefully, and am thinking through, and will continue to do so in the future, and some of the visiting artist critics. They often fly in for one week and then deliver judgments, which feels rather quick. The danger with some of the critiques is that they recast the entire conversation into a Greece-Germany binary, ignoring the rest of the world that is also part of this debate.

Adam [Szymczyk]’s words at the opening event, where he said there can be no unified story and that there is no center, have been erased from the debate around the German presence in Greece. Of course, that is an important debate, but it centers everything, again, around Europe. What I was looking for, and found to a degree, is an attempt in documenta to move conversations out of Western Europe to the Global South, to Eastern Europe, to making earlier genealogical connections. That’s a move within documenta that started with Catherine David (1997), intensified with Okwui Enwezor (2002), continued with Roger M. Buergel/Ruth Noack (2007) and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (2012), and has taken on another form with Adam with the two-city exhibition. All these attempts, with their gaps and flaws, get erased in the cynical conversations. I would like to see documenta get completely decentred; moved out of Europe altogether. But part of this critique wants to insist that this project should stay in Kassel, stay in Germany, stay in Western Europe.

Didem: I find it hard to read reviews where curators are likened to supermodels, especially when the matters in question are really matters of life and death. This attempt to render everything superficial, by this shrill argument that it’s all “posture,” and “empty gesture,” or calling it “misery tourism.” Perhaps it’s because I had more at stake in the situation and was already involved with the debates that I am willing to allow space for mistakes, while the critics pronounce from a safe distance.

Of course, there are threads in the discussions that are, with varying degrees, very urgent to discuss: like the issue of the nature of collaboration with Athenian locals—as they have called it, “Learning from Athens”; who has access to the debates and have they, again, preached to the converted; the issue of confusion regarding information surrounding the exhibition, etc. One can criticize the way some of the works were installed, or the fact that artists have needed more space, or more recently, the working conditions of the team, which I would like to know more about.

But to take, for example, one debate in regards to not representing Athens, I agree with what Symzyck said on German radio. Because if they came to Istanbul, I wouldn’t want them to even attempt to “represent” the Istanbul art scene with all its intricacies and histories, all of which occur in a very complex geography … They would not know where to start and we would be doing that already. If they wanted to learn from Istanbul, how and what would they contribute to our locality in a time of crisis (very different from that of Greece, of course)—that would be my point of concern. The question then becomes creating a platform for seeking an ethical attentiveness that does not erase difference through an all-too-facile sympathy, but which mindfully tends to that difference. So I would definitely care about being objectified or not as a subject deeply immersed in such struggles, but I would be the one negotiating it, before the visiting critics label me as the miserable local who is objectified by a European art institution; because then the critics would also objectify me, the local, and do exactly the same as what they critique d14 for. So I would not need the morality police, and I would still use the platforms to talk about the political urgencies pertaining to our specifities.

So, I do share some of the concerns of the Greek friends, but, as you say, the critique of “playing politics” also falls short and can be facile.

Naeem: I think it’s important to look at why the “playing politics” argument is seductive in a time of low trust. Critics dismiss these concerns as “recognizable currencies of discourse that preoccupy identitarian radicals” (documenta 14). This is part of a genealogy of dismissal in earlier reviews: “bitter and bleak temper of today’s identity politics” (2017 Whitney Biennial, Hannah Black protest); “the art itself changes absolutely nothing” (Okwui Enwezor–curated 2015 Venice Biennale); and the “mood-music of condemnation” (on cultural boycotts). Or look at the visceral response to the latest Turner Prize nominees: cynics tweeting about “identity issues” and “art fell into the hands of moral improvers,” and headlines about “obscure multicultural pick and mix.” There’s a predictable suspicion of, and pushback against, art practices that seek to decenter Western European domination, and/or project their politics legibly, and this suspicion is something projected also by the money center of contemporary art. This is also Eurocentric privilege fighting back to preserve its dominance, but couching it in language about “quality” and “obscurity.” It’s obscure because the critic refuse to venture outside their safety, comfort, and privilege. I think there were two good responses: Akis Gavrilidis on the Hegelian pitfalls of the documenta 14 critiques, and Paul Clinton on the assumed obscurity of the multicultural. And then there are of course, always, critics such as Holland Cotter, who have built a lifetime of work venturing outside safety zones of Eurocentric art history.

Didem: There was another line in the review you mentioned: “The particular elephant in the room of documenta should be evidence enough that ‘large international exhibitions’ are not good places to do politics.” First of all, because it was a global art exhibition, we were not gathered to make policies, but political work took place, as it always does, in all levels of interaction.

But there exists many contradictions in these discussions, and it is very hard to say what is black or white, and contentious to make overarching judgments and to attempt to talk about all the conflicts within the same space… When I talked about these questions with an artist-writer from Turkey, Merve Ünsal, she said: “Was I so eager to see good work that I wasn’t even thinking of anything else [the context] to do with d14?” Perhaps. And as I said, because we were directly implicated by the issues that were being discussed there, we saw no harm in carrying on the same conversations on a different stage.

So to me what matters here in this specific discussion with you is to talk about what “happens” in reality at the event, rather than focusing solely on what documenta stands for, talking about the art what was facilitated beyond the institutional critique, so that the dream within the dream does not get lost. Because I don’t want to only speak about the curators of d14. I feel some space and deeper thought is needed for the artists who produced work within this context and conceptual framework. So I will put aside some of the contextual conflicts and take a moment here to talk about that and that alone.

Naeem: I would like to hear about works that you want to return to. One of the pleasures of staying on into Easter weekend is that the numbers decrease, and you no longer had the guide of crowds to attach importance to events. Although, I think one of the events that you mentioned was the project at Megaron, which happened early—the one with Ali Moraly.

Ali Moraly performing Fugue: Quatrain for Solo Violin after Paul Celan’s Death Fugue (2017), developed in collaboration with Ross Birrell. Performed as part of Ross Birrell & David Harding, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs concert for documenta 14, Megaron Concert Hall, Athens, 8 April 2017. Image credit: Ross Birrell.

Didem: Yes, a day after that dinner I just mentioned, there was a performance at the Athens Concert Hall: Megaron. It was a night of supreme beauty, which similarly explored the question of exile. It was a project by Ross Birrell and David Harding based on the Polish composer Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3. Opus 36 (1976), also known as Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. The concert brought together the Athens State Orchestra and the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra (SEPO). Górecki composed the piece, a lament on loss and separation, as a consequence of war.

The concert opened with a piece for solo violin titled Fugue: Quatrain for Solo Violin after Paul Celan’s Death Fugue, by violinist and composer Ali Moraly, which was developed in collaboration with artist Ross Birrell. Fugue, from Italian fuga, means literally “flight,” from Latin fugere, “a running away, act of fleeing,” hence a word whose origin can be traced to “refugee.” Moraly is a virtuoso violinist from Syria who fled Damascus in 2012. He performed the piece outstandingly: https://soundcloud.com/ali-moraly/ali-moraly-violinist-composer.

The encore that followed the performance of Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3 was called My Beautiful Homeland, and it was composed by Jehad Jazbeh (brother of Raed Jazbeh, founder of the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra), whose joy was undeniable. It received even louder applause than the Górecki.

Conductor Daniel Raiskin’s notes for the concert open with a Dostoyevsky quote: “Beauty will save the world.” While Raiskin writes that beauty alone is not enough to change troubling conditions within the world, he also says that much greater efforts are needed from each of us in order to establish a more unified community, however difficult and intractable that may be, where mutual suffering is recognized and if not understood, then at least respected. In the concert notes, Birrell and Harding also thank the Athens State Orchestra and the Athens Concert Hall, as an expression of the spirit of hospitality and coexistence, about collective listening as a political platform in a shared space and time.

As the concert finished, I walked out in a trance state. Leaving the hall, I saw a number of friends who were personally wounded by the political problems of their geographical locales, and we looked at each other quietly.

Conductor Daniel Raiskin, Soprano Racha Rizk with the Athens State Orchestra and Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra. Performance of Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3. Opus 36: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (1976). Ross Birrell & David Harding, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs concert for documenta 14, Megaron Concert Hall, Athens, 8 April 2017. Image credit: Ross Birrell.

Naeem: The role of the exhibition is not only to memorialize pain, but to think of ways to live together again. How to conjure impossible optimism, even when many would insist that we are at the end of hope.

Didem: Indeed. And it is for this aspect alone that I wanted to take the time to look into the works that did manage to create that. And I think that effect was what d14 tried to achieve with this Athens outing, and one of its crystallizations were with Moraly and the two orchestras’ performance put together by Birrell and Harding. It was a liberating experience from the usual routines of major exhibition openings. Perhaps the concert hall became that institution Ricœur talked about, for us to be able to become fully capable subjects again; it became an institution, a space within which we were able to communicate and hear one another for a suspended time. For this helped to slow down the pace of openings, and raised the question, “When did ‘never again’ become two words again?”5

It was an act of showing up, of being present. Questions of institutional critique and relations to the locale are of course all valid, and questions that will be discussed for years to come. But I want to reclaim the moment so that it doesn’t get lost in the speed of quick critique. We can do politics everywhere, and we should reclaim all of these places where we can exercise our political subjectivities.

But also, speaking of the south and of displacement, I have to mention Banu Cennetoğlu’s piece Gurbet’s Diary, which gave me chills. Gurbetelli Ersöz was a journalist, and the only woman to hold the position of editor in a pro-Kurdish newspaper. After being arrested and tortured, she joined the guerrillas and kept a diary, which was initially published in 1998 in Germany, then in Turkey in 2014, and subsequently banned. Pages of this journal were transferred onto stones and positioned outside the garden of the Gennadius Library. The stones were inverted, and you could not read the texts written on them, yet when one knows that it is the diary of a Kurdish guerrilla, one also knows that there is an unwritten history there, imprisoned in the garden, not included in the mainstream narrative “inside the main library.” And the stones, weighing over a ton, are the literal weight of that history, of what from the region we have not been able to resolve. And those lithographic slabs are ready to be reprinted.

Reprinted in a future yet to come.

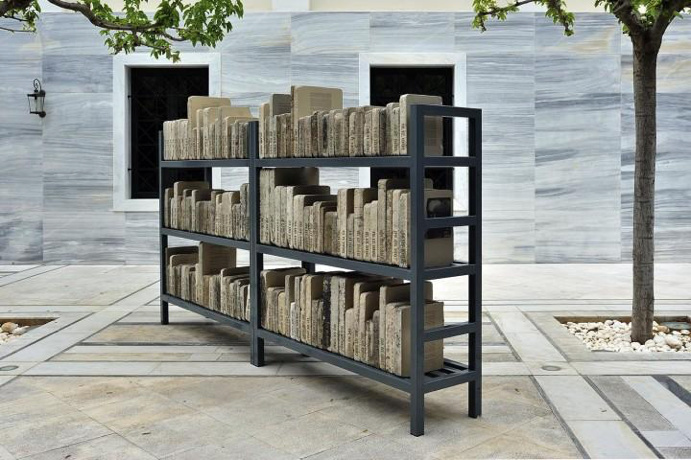

Banu Cennetoğlu, Gurbet’s Diary (27.07.1995–08.10.1997), 2016–17.

82,661 words in mirror image, 107 days, and 145 press-ready lithographic limestone slabs. Length: 900 cm, weight: 1800 kg. Stone preparation and graining, text transferring, inking, and finishing: Keystone Editions, Berlin. Gurbet’s Diary: I Engraved My Heart into the Mountains by Gurbetelli Ersöz was first published in 1998 by Mezopotamien Verlag, Neuss. Coproduced with DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program and Canada Council for the Arts.

×

NOTES

1 Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater Books, 2016).

2 Paul Ricœur, The Just (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000).

3 Mark Fisher and Justin Barton interviewed by Robin Mackay →.

4 Maria-Thalia Carras, Petros Nousias, Alexis Iosifdes, Sotiris Konstas, Dimitris Parthimos, Katherina Michaloutsou, Aggelos Mantzios, Kostas Filaktides, Sevastiana Konstaki. From the airport: Vasylis Tsatsaragos, Chrisoforos Stefanides.

5 Lina Sergie Attar, a Syrian-American architect and writer from Aleppo. She is also the cofounder and CEO of the Karam Foundation, which works with Syrian refugees. Attar speaks about the notions of home in her eloquent TED talk “Home in the Time of Displacement” →.

Editor: Rainer J. Hanshe.

In the next conversation in this series, Didem Pekün talk with the artist Banu Cennetoğlu.