*Editorial note: this interview was originally commissioned by ICA at MECA on the occasion of the exhibition “Ann Hirsch: Sharing Love.” It is reproduced with permission here.

Moira Weigel: The Scandalishious Project (2008-09) was not only about you performing for the webcam, but also how your performances created a community of responses around your work. How do you think of the responses you received from viewers online in relation to your work? I remember watching some Scandalishious fan videos in 2013, and in one of them there was a guy who talked about how much he loved your character—he was dark, backlit and kind of creepy. And then he had a dramatic stutter. This somehow humanized him to me and changed how I felt about him as your fan. Have there been reactions that are especially interesting, striking, surprising, or disturbing that have changed how you viewed the work you were making? Were there any especially notable instances of harassment or abuse—which I’m sure you must get a lot?

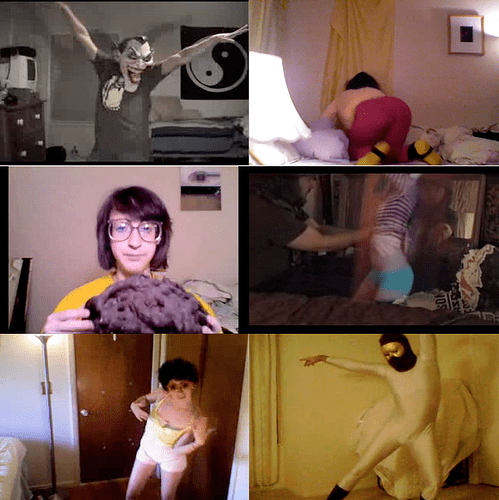

Ann Hirsch: When I started The Scandalishious Project in January of 2008, I did not expect for anyone to watch my videos or pay attention to them. I felt I was performing into a void of sorts. But after a few months, my videos were posted to forums such as 4chan, and they started getting more attention. I was intrigued by the people who followed and responded to my videos, whether it was out of lust, admiration, or hatred. I came across many people and the ones who I connected with were the people who had stories and real lives that they wanted to share with me. Men would message me and send me videos expressing their sexuality but also telling me about their lives—including stories about their wives and kids, their jobs, their deepest sexual perversions. Young girls would send me heartfelt letters telling me they wanted to be like me. I got loads of hate mail and hate videos from people telling me how ugly I was and how what I was doing was stupid. In the end, it made me realize that I was part of a community of people trying to figure out their identities in an age where your image, body, and story can be disseminated more widely than ever, and what that meant for who you are in terms of your sexuality, gender and looks. Simultaneously, it was interesting to witness how this community was responding to seeing other types of people that they might not normally encounter in the bubbles of their lives. I felt I was an amateur social scientist at the time, navigating a new world through personal anthropological fieldwork. I view the videos and comments I collected as my “data” and the artwork I have made from this experience as my “findings.”

You often used the term “attention” or “attention-seeking” to describe what you’re interested in exploring. You use terms like “camwhore” or “famewhore.” Even if you use them in scare-quotes, these are self-critical words. You are also reflective about the ways we socialize young women to constantly seek attention and affirmation and approval and then punish them for the same.

It strikes me how brave you are about exposing yourself, how vulnerable you allow yourself to be. Your work is also very funny—you’re very skilled at using wit to deflect uncomfortable moments. I think it’s the realness of your vulnerability that makes your critiques, pastiches, parodies so compelling. Even the producers of Frank the Entertainer seemed to be compelled by your “realness” or “authenticity,” [Here For You (Or my Brief Love Affair with Frank Maresca) (2011)] perhaps due to how incredibly direct, crude or funny you could be, in addition to your willingness to take risks.

What does vulnerability have to do with attention or fame-seeking? If our culture constantly encourages women to seek attention and then punishes them for it, where does vulnerability fit in? Is that a quality we are pushed to cultivate but also punished for too?

When I am creating art, if it doesn’t make me feel vulnerable in some way, it doesn’t feel interesting to me. For me, it’s vulnerability that breaks down surface interpretations of people and gives human dimension to certain “desirable” characteristics. To be “sexy” for example, is to be devoid of vulnerability—it is to present oneself as confidently sexual, even if one is terrified. Even though someone’s vulnerability could make them sexually appealing to others, the way we code “sexy” as a society is typically through the lens of unabashed confidence.

In order to be “sexy” and to appeal to one’s desired, one must attempt to “be sexy.” The most successful “sexy” people are the ones who do so effortlessly, who don’t seem to be trying at all—those who wear the most convincing masks. I think that’s also what makes the most successful romantic reality TV contestants. It’s the people who most fluidly portray “being authentic,” who don’t appear to be acting for the cameras. But the truth is, all reality show contestants are solely there for the cameras and the show becomes a game at seeing who can be the best at pretending that they’re not.

What I love about vulnerability is that it unveils the masks we put on to make us seem “sexy” or “authentic” and reveals the societal structures that perpetuate us conforming to gender and race-based stereotypes. Being vulnerable is an important tool to reveal the structures that oppress us.

What is the role of humor in your work? Do you think that you’re parodying when you make something like horny lil feminist (2015)? Or satirizing, or something else? How would you characterize the genre of those pieces?

I love using humor in my work and I think it’s such a powerful tool. Simply, humor is such a big part of our daily lives. My goal is to create humanity in all the personas I portray and stories I tell. How could someone do that without using humor? It doesn’t seem realistic.

When I was creating the horny lil feminist videos, I didn’t intend them as parody or satire; I wanted them to just very honestly represent me. I spent months making videos trying to delve deeper into who I honestly am. I wanted to show I was a feminist, with a sense of humor, who also gets off to porn despite knowing that it’s damaging for women, and that I have a cute wedding registry but also anxieties about losing my identity in a marriage to a man. And most significantly, what it means to be a woman in today’s online culture, in which your looks and opinions are on display more than ever.

Writing on your work often emphasizes how you use reality television, webcams, digital video, video sharing sites, and so on to explore how women are looked at. Or, in other words, to explore different kinds of interpersonal relations. But it strikes me that your work is very interested not only in how women are looked at by others, but in how we use screens to produce ourselves. What role do the technologies you use play in the production of selfhood, a well as interpersonal dynamics?

For women, we have a long history of being looked at, mainly by men, who have also historically authored all imagery of us. In the last decade, women now have the ability to produce their own imagery and disseminate it widely. This change has huge potential, and to some degree I think women—and also people of color and LGBT people—have used these new platforms to create human, empathetic depictions of themselves. I think this is a huge reason why we have suddenly come to find ourselves living in an era defined by a growing acceptance of trans bodies, Black Lives Matter, and a new wave of feminism. However, it’s not all utopian. The internet exerts its disciplinary control through creating an atmosphere of “likes” and “virality” and pleasing the lowest common denominator. So often we feel we must conform to more stereotypical portrayals of ourselves in order to be part of this attention economy and to have a voice. This has happened for me on a personal level—where, in order to be seen, I know sexy selfies will be liked the most. But I don’t want to have to show myself in that light in order to have a voice. So I have to choose whether I want attention and loud voice or if I want to show myself in a more humane manner—by that I mean show myself as a holistic person who isn’t just a sexual object—or if there is a way I can do both.

Can you talk about the drawings in this exhibition, Dr. Guttman’s Office (2014-15)? How do you feel this different, non-digital medium interacted with or expressed differently your interest in gender, the body, self-representation? Is the doctor’s office a performance space? Have you always drawn?

My drawing and painting practice has been really important for me because it’s the medium in which I am able to express my ideas less didactically. I started taking drawing and painting lessons when I was 12: my childhood therapist recommended it to my parents since all I did in her office was draw obsessively. I left drawing for a long time because I developed interests in newer media like video and performance, but in the last few years I’ve been using drawing as a way to explore my subconscious thoughts, which, not surprisingly, are often issues I wrestle with around gender roles and conformity. I’ve been making art for nearly 10 years almost exclusively about what it means to be a woman. When I revisited old drawings I had made as a child, which I uncovered while visiting my parent’s house recently, I was surprised to see this content shared in these drawings—I had the epiphany that this is something I’ve been wrestling with my whole life. So the paintings in Sharing Love show how my obsession with gender manifested at a young age, and how the issues in those old childhood drawings still exist for me today.

Moira Weigel is a writer and academic, currently finishing a PhD in Film and Media and Comparative Literature at Yale University. Previously, she earned a BA from Harvard and an MPhil from Cambridge. Her research focuses on where the history of technology intersects with the history of ideas—particularly ideas about nature, life, and gender.

Moira’s essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, and The New Republic among other places. In May, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux published her first book Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating. The New York Times called the book “addictive and accessible”; the New Yorker said it was “perceptive and wide ranging,” while The New Statesman referred to it as a “radical feminist Marxist tract disguised as a salmon pink self-help book.” You decide.

*Image: Ann Hirsch, The Scandalishious Project, 2008–09. Video, color, sound, 42:30 minutes. Courtesy the artist.