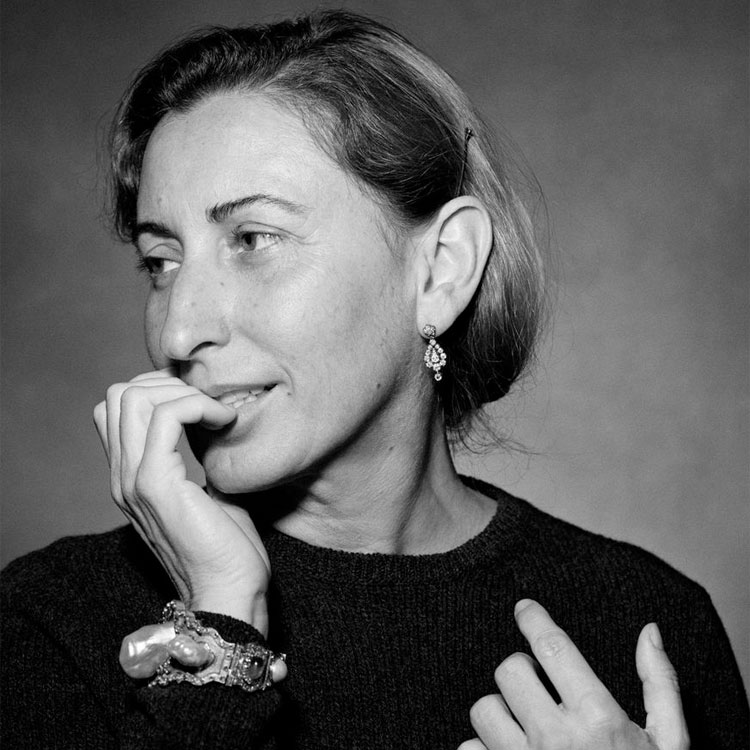

For the Guardian, Rachel Cooke writes about fashion designer, businesswoman, and art collector Miuccia Prada, whose new Fondazione Prada outpost in Milan recently opened. Prada is surprisingly forthcoming about how she feels about pretentious attitudes in the fashion world, being an art collector, and taking art out of the public sphere. Check out part of the profile below, or read the entire piece on the Guardian’s website here.

In her home city of Milan, the Fondazione Prada has just opened a vast “campus” for art on the site of an old distillery close to a railway line. I saw it the day before, and gasped at its size, its ambition, its severe industrial minimalism (even the children’s play area is grey and white). At 19,000 square metres, its collection of exhibition spaces – one is several storeys high and called the Haunted House, another is a grotto deep underground – is twice the size of Renzo Piano’s new Whitney museum in New York, and at least three times as elegant. Designed by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, and filled mostly with work from the permanent collection of the Fondazione Prada, it has been received with some rapture by the critics, and with some gratitude by the Milanese, who will doubtless continue to make good use of its retro cafe – a 50s fantasy in green vinyl designed by the film director Wes Anderson – irrespective of whether they ultimately fall for the charms of Damien Hirst’s Lost Love (a gynaecologist’s chair in a large aquarium the artist made in 2000) or Nathalie Djurberg’s The Potato (a walk-in fibreglass tuber complete with purplish eyes that dates from 2008).

But is the woman who conceived it triumphant, over the moon, high on a combination of acclaim and relief? No, she is not. Only with the greatest reluctance, it seems, would Prada ever describe herself as pleased. “I’m always thinking about the next thing,” she says, her mouth turning down. “So I don’t enjoy anything.” But it’s so generous, her city of a gallery, with its square, its library, its cinema (visitors will be able to spend the day there for €10). She shrugs. “Well, I don’t feel generous. The result is maybe generous, but I didn’t start with that. I started with an idea, which was to do something that I think is important and relevant. I wanted to make culture attractive to the young [so that they would see] that it is necessary to your life. My intuition – and after many years, I realise that my main quality is intuition – was that it would be good to have a place where people could live with ideas.” Culture, she insists, must come to be perceived not as an extra, as a form of “decoration”, but as deeply useful. In what way useful? “It can answer political and even existential questions.”

The Wes Anderson designed bar in the Fondazione Prada, Milan. Facebook Twitter Pinterest

The Wes Anderson-designed bar in the Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photograph: Ollie Wainwright

She and her husband, Patrizio Bertelli, the chief executive of Prada, established the Fondazione Prada in 1993, and it was only after this, she says, that they began buying art. “We had to learn, and quickly. Until that moment, my cultural background was in literature, politics, cinema, theatre and dance. Art? I was never interested in it.” So who did they buy first? “Nino Franchina [the Italian sculptor and painter] was probably the first… ” She grimaces. “You know, you look and you study and you like it and you appreciate it and eventually you buy it. That’s not very noble, the buying part, but I have to confess it. I grew up with the idea that art is for everybody and not a matter of private ownership, but sometimes you want to have it.”

Happily, she finds she’s now less interested in buying than before: when I tell her, for instance, that the loveliest things I saw during my visit were the two boxes by the American artist Joseph Cornell displayed in a 15th-century marquetry studiolo-cum-sideboard, her reply is unsentimental. “I’d always liked Cornell, but I bought those because I wanted to have something to put into the studiolo,” she says.

Her resistance to – or embarrassment about – the concept of ownership extends to the word “collector”: she and Bertelli may own some 900 pieces of contemporary and modern art, but she flinches if you use the term in her presence. “I hate the idea of being a collector,” she says. “I really hate it. I’m not a collector.” Nor is she willing to be described as a patron, for all that she is well known for commissioning artists (no interview with Prada is complete without mention of the Carsten Höller slide by which she may, if she so chooses, depart her office at night). “As much as I don’t feel like a collector, I’m even less a patron. I am and want to be an active part of shaping culture, but I am patronising nothing. I hate all of that. I don’t want to be perceived like that, which is why we never sponsor exhibitions.” So what is she, then? “When I started becoming friends with the artists, there was a shift. It was like sharing personal problems.”

Crikey. Building galleries and commissioning work is some way to share personal problems, not least because, however she likes to describe it, it brings with it such responsibilities: she has it in her power not only to make or break a career, but to influence the market. Does this ever make her anxious? “I can’t speak about the market,” she says. “But it is a problem in every field: the hunger for the new. In fashion, everyone wants a genius, and in another few days, they want another. It’s really bad. The problem is that people think an artist has only one great period. But we all live longer now: an artist can have a comeback.”

Prada and Bertelli have always strived to keep their fashion business and their interest in art quite separate. I think this has to do with their fear of vulgarity. They would hate anyone to think the Fondazione Prada was simply another, albeit more esoteric, way of selling handbags. But even so, the two realms must influence each other. How could they not? She smiles. “Yes. I prefer that they don’t in principle. But of course they do. I’m very proud of my job [as a designer]. I used to be ashamed of it because I was educated, I was a feminist. But finally, I am proud of it. I earn my own money, which is a huge thing for a woman. The speed of fashion has taught me so much, and it’s a very open world by its nature. Movies, music: we need culture for our job. This speed is useful in the art world, and for sure the art world is useful in my job. It’s such an obvious collaboration, and deep down my life is one. Every man and woman wants to dress well. That’s how they express themselves.”

She can’t believe the snobbery that exists around fashion. “It’s an injustice,” she says. But isn’t it the case that some people also take it far too seriously? It’s only frocks, after all. For a moment, she is silent. Perhaps I’ve offended her. But then she breaks into laughter. “Actually, I don’t care,” she says. “I really don’t care at all!”

*Image of Miuccia Prada above courtesy azureazure.com