At Public Seminar, McKenzie Wark engages in a provocative thought experiment: if we examine our economic system based on what it is now, rather than on what it was in the past, can we still say that this system is capitalist? Wark argues that the answer is no—but this is far from good news, because the system we have now is even worse than capitalism. Read an excerpt from the piece below, or the full text here.

But maybe it would be interesting, politically and aesthetically, to take the other fork of the binary here. Instead of the idea that this is not capitalism, its better, what if we explored the idea that this is not capitalism, but worse? This also meets a lot of resistance. This I can tell you from experience, having tried to write variations on this text for fifteen years. Nobody wants to leave the certainty of the devil they know, or think they know, for something that promises to be worse.

Interestingly, few people will even attempt it as a thought experiment. There really is something fundamental to the belief that this is capitalism. It may even be the defining feature of ideology today. Ideology today is not the acceptance of a neoliberal structure of feeling or habits of thought and action. Ideology today is clinging to the belief that this is capitalism …

So how is it worse than capitalism? The vectoral infrastructure throws all of the world into the engine of commodification. There is nothing that can’t be tagged and captured via information about it and considered a variable in the simulations that drive resource extraction and processing. Quite simply, we have run out of world to commodify. And now commodification can only cannibalize its own means of existence, both natural and social. Its like that silent film where the train runs out of firewood, so the carriages themselves have to be hacked to pieces and fed to the fire to keep it moving, until nothing but the bare bogies are left.

It is worse also in that rather than some vague multitude, there’s complex class alliances at play in the political space. The trickiest part of it is the politics of the hacker class. Which after all is the class most of us here belong to. Yes, it sometimes appears as a privileged class. But it is a class that has a very hard time thinking its common interests. Largely because the kinds of new information its various sub-fractions produce are all so different. We have a hard time thinking what the poet and the scientist and the engineer have in common. Well, the vectoral class does not have that problem, what all of us make is intellectual property, which from its point of view is all equivalent and tradable as a commodity.

Also, the hacker class experiences extremes of a winner-take-all outcome of its efforts. On the one hand, fantastic careers and the spoils of some simulation of the old bourgeois lifestyle, on the other hand, precarious and part time work, start-ups that go bust, and the making routine of our jobs by new algorithms designed by others of our very own class. Of course it is always a tough argument to propose common interests among subordinate classes. Counter-hegemony is hard. Hackers, like workers or farmers, are distracted by particular and local interests. Class consciousness is rare among hackers. Most of us are rather reactionary — even in the nontechnical trades. But then class consciousness is always a rare and difficult thing. Unlike other identities, it has to be argued contrary to appearances.

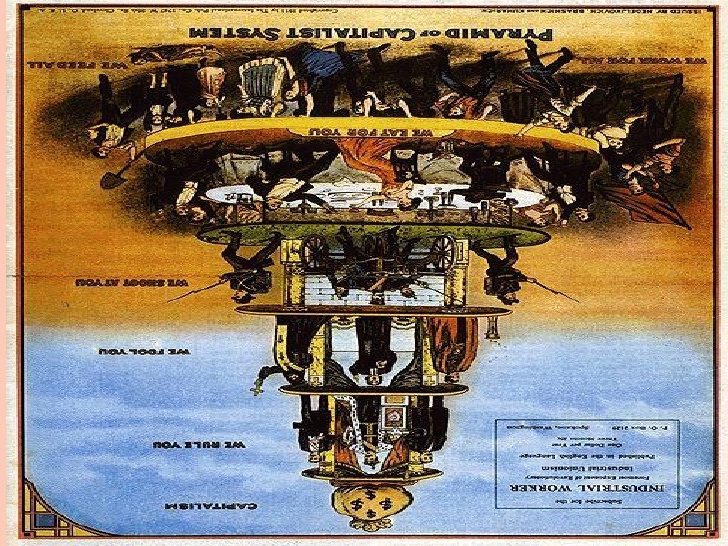

Image via Public Seminar.