At Public Seminar, McKenzie Wark surveys the books of Chris Kraus, from her seminal debut I Love Dick to her latest novel, Summer of Hate. You might think that nothing new and interesting could be said about Kraus’s work, since its been covered exhaustively over the past few years by a younger generation of aficionados from the spheres of art and literature. But you’d be wrong. Wark suggests that Kraus’s books expose “the means of production of theory,” and take theory more seriously that academia does by asking how it illuminates the pleasure and abjection of a real physical body—her own. Here’s an excerpt:

Sometimes reading Chris Kraus is like archaeology. Somewhere beneath the surface of the text are some rich fossil layers. Call it the hyperreal strata of the Anthropocene. Some of it smells like the New York of a certain era, all speed-sweat and peroxide. On top of that layer is something else, something that filled the niche when those punk creatures went extinct. Once there used to be whole separate ecologies of art and fortune. There were poets, performers, artists of a sort. They made their own rules for glory. Then they went away, and after that comes pedigree creatures, sired by great names for brilliant careers.

Among other things, Kraus has written the Domesday Book of the lost wilds and commons of New York. “All of New York’s mystery had long since been depleted.” This is perhaps the case with a lot of the cities of what the Situationists so usefully called the overdeveloped world. Kraus: “There is no longer any way of being poor in any interesting way in major cities like Manhattan.” As late as the winter years of the eighties, other lives, other communities, other values still survived in neglected corners. But is that still possible? “It’s only rarely that the overwhelming sadness of the city galvanizes into anything like rage. And when it does, this rage is quickly channeled into new careers in the art world.”

As people get older they start to think it is all over and the good old days are gone. As a Kraus-like character says of LA: “There’s no alternative hierarchy of glamour here. Those who work outside the gallery system are simply losers.” And yet the actual Chris Kraus could still celebrate the brief and brilliant life of the Tiny Creatures scene in LA’s Echo Park: “What all these people do best is collage. They’re all on speed….” So while her books are in part like archaeological records, they are also blueprints for how to turn your own quirk and smarts and boredom into its own scene, with its own intensities, if only for a time.

Perhaps this is not the least reason Kraus’ books have a following. They are about working the inside-outside margin. As the Kraus-character says in Summer of Hate: “She saw no boundaries between feeling and thought, sex and philosophy. Hence, her writing was read almost exclusively in the art world, where she attracted a small core of devoted fans: Asperger’s boys, girls who’d been hospitalized for mental illness, assistant professors who would not be receiving their tenure, lap dancers, cutters and whores.”

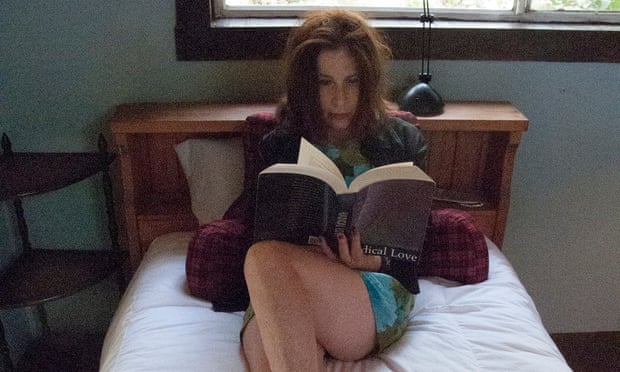

Image of Chris Krauss via the Guardian.