Text by Marlie Mul

I first came across the 19th Century French painter Rosa Bonheur while preparing the exhibition I co-curated at Kunstverein München together with Judith Hopf. Bonheur is reputed to be the first female artist who managed to make a living from her work, and when I looked into her backstory I became particularly interested in how she, as a woman, managed to manoeuvre through the art world of her time and find a position for herself within it. I was curious to know what drove her to overcome obstacles set by a social construction dominated by male patriarchy. What qualities did she possess that made it possible to disestablish this power at the time and to use it in her own favour?

Crucial to this reading are several biographical texts on Bonheur, published both before as well as after her death in 1899. Moreover, it appears that during her lifetime Bonheur was fully aware of the power a biography could have upon an artist’s reception and exercised fastidious care over her own memoir. As such I would like to consider how her biographical portrayal – both by others and herself – has had subsequent influence upon how she, to this day, is seen as a pioneering figure for women in art. And in this respect, it is important to consider whether Bonheur’s legacy is based on her being first a painter and then a woman, or a woman first and then a painter.

The cult of personality intensified from the mid-19th Century onwards. While glorification and praise of certain figures was at the time nothing new, the accelerated machinery of print media brought facts and information about celebrated artists, writers, and political figures to wider public attention faster than ever before. A newly acquired position as a free market agent also increased competition between artists, which forced them to work on establishing and marketing their own persona. With trends shifting from academic Classicism to reactionary Realism, the artist was then seen as a passionate individual that used their skill to express emotion. The increasingly wealthy middle class had also started to spend money on artwork for their homes, and wanted to know more about an artist’s persona. This in turn established the artist’s biography as a way to decode their art, bringing the person behind the artwork to the fore. It is here that an economy around biographical details came into existence and with artists aware of this, they often adapted to it strategically.

Bonheur’s first biography Les Contemporains: Rosa Bonheur was written by Eugène de Mirecourt and published in 1856 shortly after her work gained recognition. She was however incredibly dissatisfied with the way in which de Mirecourt depicted her life, as he failed to describe the personal relationships she felt had so much influence on her persona. She spent endless time making corrections in the margins of his text and such was her annoyance the artist became obsessed with writing an autobiography that would do her own life justice as she saw fit. However because Bonheur did not consider herself good enough a writer, she searched instead for someone who could write it for her. It seemed almost a prerequisite that someone should be willing to enter into an intimate relationship with her in order to tell the artist’s story from her own position. Toward the end of her life she met the young American art student Anna Klumpke in whom she found the intimacy and devotion she had been looking for. Klumpke became her second partner and they set out writing her autobiography together. Klumpke ultimately completed the book after Bonheur’s death, writing part of it as if written directly by Bonheur herself, hence the title Rosa Bonheur: the Artist’s (Auto)biography.

This publication is the main source of interpretation when looking back on Bonheur’s life and, importantly, her work. While its narrative is personal and therefore emotionally driven throughout, her career and close analysis of Bonheur’s paintings while alluded to, nevertheless remain a subtext. Given this, I myself do not aspire to add yet another biographical strand to the artist’s past, however feel it necessary here to address certain notable facts about her life. A realist painter of animals, or animalière, it was the artist’s painting The Horse Fair (1852) that brought her recognition. First exhibited during the Paris Salon of 1853, Bonheur’s depiction of Percheron horses inspired by Delacroix and the Parthenon frieze was noticed by Empress Eugénie de Montijo, the wife of Napoleon III. The Percheron was well known to be the French royalty’s favourite breed of horses, and one can attribute Bonheur’s painting to her support from the royals; the Empress soon brought her influential friends to Bonheur’s studio. This led to Bonheur becoming the first woman to receive the Legion d’honneur in 1865, a civilian order of merit established by Napoleon Bonaparte at the beginning of the 19th century.

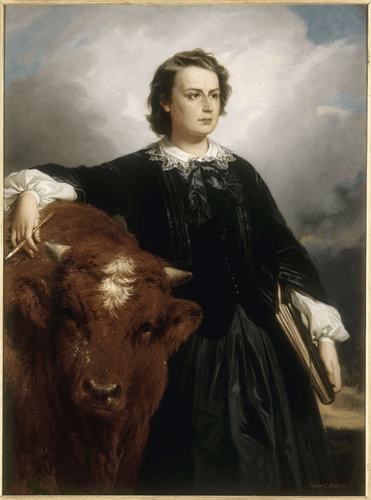

Edouard Louis Dubufe, “Portrait of Rosa Bonheur,” 1857. Symbolic of her work as an Animalière, the artist is depicted with a bull. Image via Wikipedia

Bonheur’s naturalistic painting style coincided with a time when Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet’s banal Realist depictions of the everyday and the ordinary had a coarseness that was read as ironic, and thereby politically provocative. Realism however allowed her to paint scenes to her own liking because it made way for a movement away from Classicism’s worship of the past. By making animals the central and nearly sole subject of her paintings, Bonheur adopted a visual strategy that brought her an audience of established authority; firstly the French royals, and later the new rich of the American and British middle classes. Her chosen subject matter and highly decorative compositions were skilfully executed and thus accepted as works of art. Strategically using conservative imagery also suggests a careful political position of neutrality. At the same time, one can sense from her paintings that Bonheur felt at one with the animals she portrayed. Painting animals may have been a way to remove herself from any direct association with gender roles, yet as much as she professed to identify with animals, she portrayed them almost as human with a caring, ‘maternal’ eye. For example, numerous depictions of dogs remind of human portraiture. In the painting The Lion at Home (1881) she goes to great effort to show the paternal protection of a family of lions, while in her studies of herds of sheep – seemingly without any will of their own and driven around by shepherds in the Scottish Highlands – hint at an obedient compliance inherent to moving in crowds.

Large parts of the biographies written on Bonheur are devoted to her father, Raymond Bonheur, and his devout affiliation with Saint Simonianism that was to have so much effect on her upbringing and later attitude to life. The Simonianists were a social religious group that was structured along a similar hierarchical structure as that of Christian religion. The central principles of the movement are often presented as early forerunners of Socialism, with social regeneration through the privileged classes helping the working classes being their main ideology. Importantly, the Simonianists believed in a god that was both male and female, and a large part of their campaign was fighting for the equality between men and women. This was also expressed in part in their dress, which looked like equestrian apparel and included trousers for women. Bonheur’s father taught drawing and he stimulated his daughter’s career as an artist from an early age. In Rosa Bonheur: the artist’s (Auto)biography she muses on going to school together with boys, which wasn’t standard for the time, and how she always saw herself as an equal: ‘it emancipated me before I knew what emancipation meant.’

Bonheur’s special position as an artist and public figure is well illustrated by the fact that in a time when women were not permitted to freely wear trousers, she had a permit from governmental authorities allowing her to wear them. Although there is in the biographical texts a strong focus on what is referred to as Bonheur’s ‘mannish’ appearance and behaviour – emphasising her wearing of trousers and chain smoking – I see these at attempts at underlining her strength of character or labelling sexual orientation. After all, she lived in a period before any recognised women’s movements were officially labelled as feminism, and dressing like a man must have then created instant commotion. As always, but at the time even more explicitly so, rejecting art’s hierarchical structure was problematic for women, as it could affect their status as professionals. Purposely dressing ‘like a man’, one could say that Bonheur’s ‘masculinity’ was entrepreneurial as it played into the desire for personality, complaisantly affiliating with the machismo of the business she was in in order to infiltrate the maleness of the art world and gain equal footing in it. If this was to have been effective in any way, could her attire now be seen as a deliberate strategy?

A woman wearing trousers at that time would have suggested both the absence and the presence of masculinity, blurring fixed conceptions about how bodies were classified. Bonheur spoke about this topic in restrain, emphasising that she wore trousers for practical work purposes – for example, when she studied animals in slaughterhouses – rather than to look more ‘mannish’. Wearing trousers from an early age as part of the Simonianists’ attire, she would no doubt have been all too aware of the power anatomy has to shape experience. I don’t believe though that it was her objective to be in a position of power the same way that men are. From Bonheur’s perspective, which is also in relation to her upbringing, her style of dress was not a way of demonstrating that she was emancipated, but a way of being truly emancipated. Instead of seeking conformation from existing hierarchical structures, she showed that she would do whatever she wanted. In my opinion she seems to have consciously lived a life of revolt that was intuitively inspired and seemingly aimed at pursuing her one passion – the study and painting of animals. What might appear as strategy served the purpose of creating a bubble in which to work and live freely with a female partner in a cosmos of mutual care and balanced daily activities removed from the hierarchy that rules on the outside.

Seeing that there is generally not much analytical attention paid to the content of her painting means her emotional life takes the upper hand in Bonheur’s legacy, consequently underpinning the interpretation of her artworks. At the same time however, her work and life story are naturally and completely intertwined; her personality would not be of importance to us if her paintings weren’t there to carry it. However, I would state that it is for a large part due to the existence of biographical material that we still discuss this particular female artist’s relevance now, and that this literature was something she seemed self-aware of in her own lifetime. In conceptualising the show, perhaps Bonheur was a recurring figure of reference because of the position she holds as a female artist that worked her own way towards self-sufficiency in a time when female artists were not generally accepted and art made by women was seen as a very rare phenomenon. As such, Bonheur persistently worked her way past the seemingly indestructible obstacles she came across.

This text was originally commissioned by Kunstverein München in 2014 for the yet-to-be published catalogue of the project and exhibition “Door Between Either and Or” from 2013. It has been published in Mimi Magazine (a one-off self-published magazine by Anna-Sophie Berger, Marlie Mul, Anne Speier, Philipp Timischl and Min Yoon) in May 2016.

*Image above: Rosa Bonheur, “Lion At Rest” (c.1880). Image via arthistoryarchive.com