Zak Stone, a writer based in LA who has previously covered tech and the sharing company for magazines like Fast Company, rented a house via Airbnb with his parents in Austin two years ago for a Thanksgiving getaway. After awaking Thanksgiving morning Stone’s father tried out the property’s tree swing, which immediately broke under his weight and crushed him, as the tree had died. Stone’s father succumbed to his injuries later in the hospital.

While the odds of all this happening are staggeringly low, it’s even more astronomical and uncanny that Zak Stone is a writer who had previously written optimistically about Airbnb and the Silicon Valley “build it now, mend it later” ethos the company represents. This text follows his father’s death and Stone’s unfurling realizations that the safety precautions in proper hotels and bed and baths are there for a reason, along with many other interesting reflections about the unregulated “sharing economy” in general.

While this is a great read, it is also a heartbreaking one, so I would recommend clicking away if you’re prone to Monday blues. Below are some excerpts from Stone’s text, find the full version on Medium.

Also related: e-flux journal’s issue on Architecture as Intangible Infrastructure.

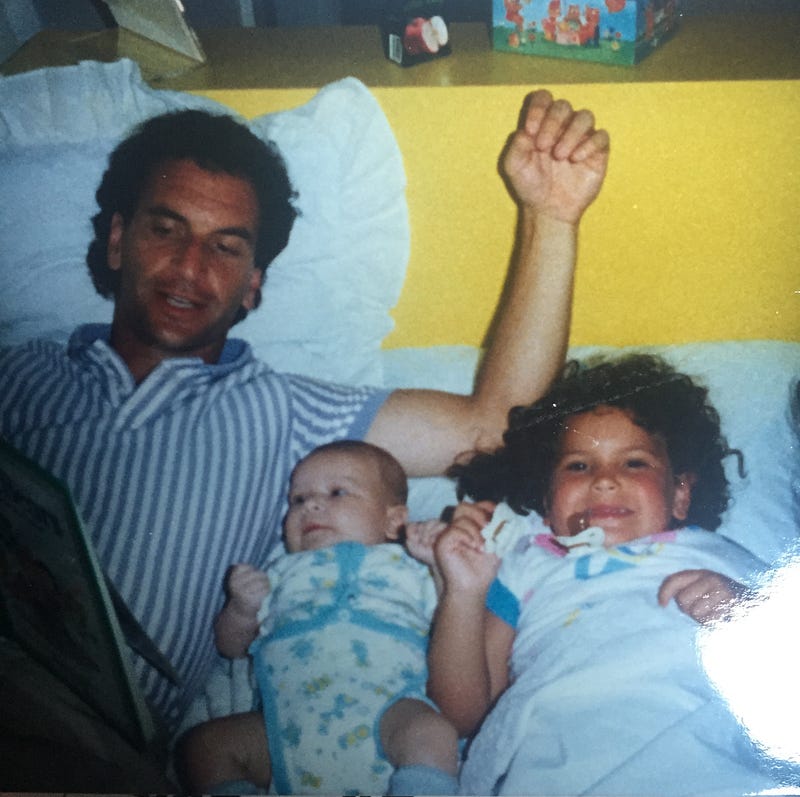

*Family photo above via Medium and courtesy the author.

It’s only a matter of time until something terrible happens,” The New York Times’s Ron Lieber wrote in a 2012 piece examining Airbnb’s liability issues. My family’s story — a private matter until now — is that terrible something.

Since the incident, I’ve felt isolated by the burden of this story and my sense of obligation to go public with it, but with an unclear aim. Am I “raising awareness,” in the familiar path of the victim speaking out? And if so, to what end? What will sharing my story really mean for Airbnb? Could the company, with its reportedly $24 billion valuation and plans to go public, do more to ensure the safety of the properties where millions of guests stay each year? As Airbnb rises into a global hospitality behemoth — reinventing not just how we travel but how we value private space — what responsibility does the company have to those who have given it their dollars and trust?

Startups that redefine social and economic relations pop up in an instant. Lawsuits and regulations lag behind. While my family may be the first guests to speak out about a wrongful death at an Airbnb rental, it shouldn’t exactly come as a surprise. Staying with a stranger or inviting one into your home is an inherently dicey proposition. Hotel rooms are standardized for safety, monitored by staff, and often quite expensive. Airbnb rentals, on the other hand, are unregulated, eclectic, and affordable, and the safety standards are only slowly materializing.

To be fair, Airbnb has always put basic safeguards in place, like user reviews. But its general approach to safety is consistent with Silicon Valley’s “build it first, mend it later” philosophy. When an early product produces negative outcomes and bad press, apologize. Then, fix it; make it better. “We let her down, and for that we are very sorry,” CEO Brian Chesky wrote in 2011, after a San Francisco woman, “EJ,” returned home to find her apartment destroyed, her possessions burned, and her family heirlooms stolen. When her blog post documenting the ordeal went viral, they changed their policy to guarantee $50,000, then $1 million, in property damages and hired enough customer service reps to man the phones 24–7.

Less has been done to protect guests against hosts, presumably because fewer horror stories have gone public. When an American man was bit by a dog left behind at a homeshare in Argentina this March, Airbnb refused to cover his medical expenses until after The New York Times began inquiring. (About that incident, Airbnb told me, “Our initial response didn’t measure up, and we’re constantly auditing our customer service team to ensure these kinds of errors don’t happen. In this case, we worked with the guest to help cover his medical and other expenses, and we provided a full refund of his booking costs.”) Home safety tips were not incorporated into the sign-up process for new properties until after my father’s incident.

Even so, nothing is currently done to make sure hosts actually comply with safety guidelines (or even read them), which is a problem particularly for newer properties on the platform, which Airbnb’s customers, as opposed to employees, are left to vet for safety. Should the company demand more from aspiring hosts — submitting an application, passing a safety quiz, hopping on the phone with an Airbnb safety rep, or undergoing a home inspection (an idea which Chesky himself has suggested) — they’d burden the seamlessness of the minutes-long sign-up process and deter new registrations.

…

That night, back at my aunt’s house in Austin, we silently ate pumpkin pie and lit the Hanukkah candles, joylessly going through the motions of tradition. As I sat watching the flames flicker, that day’s violent movie streaming in my mind (as it’d continue to do so, nearly non-stop, for months), the realization that we had booked a second night at the cabin suddenly jarred me. Had the company been told about the accident? What was there to even say? I logged on to Aibrnb’s website and looked up the customer service number.

“There was an accident, and we’ll need a refund.”

I remember uttering an approximation of those feeble words to the chipper customer service agent who answered Airbnb’s hotline, his voice young and sweet, clearly not yet jaded by the job. A tree fell on my dad, and what are you gonna do about it, and how would that look to see “Airbnb Killed My Dad” on the internet. The guy panicked, as expected, put me on hold, then asked to call back. Later, I spoke to a higher-up, collected myself and said, “Let’s talk about this another day.”

I wasn’t sure what I was hoping to get out of the phone call, exactly. I knew that I was letting emotion and shock rule my response. But for some reason, remembering that it was Airbnb who had led us to this deadly cottage made the incident feel suddenly, oddly personal. As a journalist who has written for startup-cheerleading publications like Fast Company and Good, I’d spent much of the past few years writing about the emergence of the sharing economy from a highly supportive perspective. While covering a community hearing about a proposed ban on Airbnb in Los Angeles two months before my dad’s death, I was far more sympathetic to Airbnb supporters — the hosts claiming the website helped them pull their homes out of foreclosure — than to its detractors — bitter neighbors complaining about Airbnb guests snatching their parking spots and making noise at night. Moreover, as a traveler who had booked accommodations through Airbnb all over the world, I had trusted the platform and “community” enough to introduce it to my family.

…

Airbnb is impossible to avoid in my daily life, in conversations with friends and in my work as a journalist, in pop culture and in the news, in the cheeky and controversial billboards reminding Californians of everything they can afford thanks to the company’s taxes. All the while, over the past two years, I have been working on this piece, and it’s been an important part of letting go of the trauma.

Matter first reached out to Airbnb with factchecking queries over the summer. The company has been dutiful and respectful in its responses, but getting the answers took longer than we expected. As a result, my story arrives at a moment when tension between Airbnb and cities around the country is coming to a head.

Communities are trying to process the deep impacts of Airbnb on domestic space, real estate, travel, hospitality, and the risks and benefits we ascribe to such things. Supporters of Airbnb have argued for the rights of homeowners to make money off their own property, and for the ability of home-sharing platforms to police themselves. The company has rallied to its hosts’ defense, offering legal support and helping start Peers, an association for Airbnb hosts, Uber drivers, and other freelancers that turns out opposition to legislation to curb companies operating in this on-demand economy (including at the community meeting in Los Angeles I wrote about). In San Francisco, Airbnb spent nearly $9 million to successfully defeat Proposition F, which would have capped the number of nights a host can rent out her property at 75 per year and enable the city to fine home-sharing sites up to $1,000 per night for non-compliant properties.

Elsewhere, some landlords and neighborhoods are working to expel informal hotels from apartment buildings and quiet residential blocks. Affordable housing advocates have called Airbnb the gasoline lighting up scorching rental markets in gentrifying areas, arguing that it pushes up prices by transferring housing inventory from locals to tourists. Hospitality industry players, threatened by Airbnb’s rapid ascent into a brand worth more than the Hyatt, are lobbying statehouses to introduce legislation blocking short-term rentals. Elected officials and community groups, for their part, have contributed funding to campaigns like Share Better, which features videos of Airbnb guests confronting mouse droppings and unfinished construction.

Airbnb is touting its success in San Francisco as a sign of its growing electoral power, on par with groups like the NRA or Sierra Club in their ability to mobilize supporters to influence elections. They’ll certainly have plenty of new arenas to test their tactics. At a recent meeting of the New York City Council — which is considering introducing fines as high as $50,000 on homeowners who break short-term rental laws — local lawmakers clashed with Chris Lehane, Airbnb’s head of global policy and public affairs. They argued over who was really looking out for the best interests of rent-burdened middle-class families: afterward, the company agreed to comply with the Council’s request for data on illegally run rentals.

In 2014, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman published an analysis of four years worth of subpoenaed data on rentals where the host was not staying on the premises. It showed that more than a third of the revenue generated by those Airbnbs in New York City — $168 million — went to informal hoteliers who controlled anywhere from three to 272 properties, some of whom earned millions of (likely untaxed) dollars annually. Seventy-two percent of all rentals were either violating housing laws against short-term rentals or using commercial properties for residential purposes. And in 2013, as many as 200 listings on Airbnb appeared to function as informal hostels, which are outlawed across New York State for safety reasons. One Brooklyn Airbnb listing managed to cram in 13 visitors on an average night. In typical Airbnb fashion, once the news of the quantity of illegal hotel bookings went public, Airbnb scrubbed 2,000 listings from its site overnight, just in time for an important court date in New York.

In New York State, the Multiple Dwelling Law prohibits New Yorkers from renting out their apartments for less than 30 days if they’re not staying on the premises. It is intended to preserve affordable housing and to help keep tourists out of properties that aren’t up to fire code. As routine inspections by New York City’s Department of Buildings show, illegal hotels often create dangerous scenarios for guests — by neglecting to offer automatic sprinklers, fire alarms, or proper means of egress, among other violations. “Visitors who stay in transient residential occupancies are not familiar with the layout of the building, including the exit stairwells,” Thomas Jensen, chief of fire safety for the FDNY, explained in an affidavit. “Occupants of transient accommodations therefore are likely to find it more difficult to evacuate the building quickly.”

While New York requires hotels to adhere to much stricter safety standards than apartment buildings (portable fire extinguishers, automatic sprinklers, posted emergency guidelines), unregulated hotels — whether a sketchy commercial operation or a branding consultant’s Williamsburg loft — usually don’t. “[T]he visitor is thus placed at significantly increased risk of injury or death,” adds Jensen, noting that the stricter standards Airbnb rentals may ignore have helped decrease fire-related fatalities in New York City by more than 80 percent from 1976 to 2013.