Join Erica Love and João Enxuto [@EnxutoLove] on this thread for live responses to today’s presentations at the Avant Museology symposium at the Walker Art Center.

Image: Arseny Zhilyaev, Cradle of Humankind, 2015. Installation view, Future Histories, Venice Biennale, 2015. Photo: Alex Maguire. Courtesy of the V-a-C Foundation and the artist.

Symposium Schedule—SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 20

1:00 pm—Opening remarks

1:05-1:45 pm—Arseny Zhilyaev

1:45-2:30 pm—Fionn Meade and Walid Raad in conversation

2:30-3:30 pm—Boris Groys

4:00-4:45 pm—Jonathas de Andrade and Adrienne Edwards in conversation

4:45-5:30 pm—Hito Steyerl

1:05 pm | Arseny Zhilyaev

The editor of Avant–Garde Museology reflects upon the main conclusions drawn from his research for the book. Today many contemporary artists uphold the historical avant-garde’s negative attitude toward the museum as an institution for maintaining the class enemy’s order of things. In 1917, with the new social agenda of the Russian Proletarian Revolution, art was transformed from a bourgeois ghetto into a means of production in the service of a new communist society and a new human. Marxist museology appeared to provide a possible solution to the dilemma the historical avant–garde posed to artistic institutions. The display methodology and concept of the post–revolutionary museum drew closer to historical materialist practice, even echoing a number of avant–garde principles. According to Zhilyaev, the final stage in establishing museology as a means of production and a medium for social and human development is best described by the philosophy of Russian Cosmism, which envisioned the museum of art as the ultimate frontier for human expression—based not on social or physical contradictions, but on overcoming any limits imposed by nature or Earthbound political or economic orders.

1:45 pm | Fionn Meade and Walid Raad

Fionn Meade and Walid Raad discuss the artist’s work, which includes The Atlas Group, a 15-year project (1989–2004) about the contemporary history of Lebanon, and the ongoing projects Scratching on Things I Could Disavow and Sweet Talk: Commissions (Beirut). Raad is an artist and a professor of art at Cooper Union, New York.

2:30 pm | Boris Groys

The Art Museum and Its Discontents

There is a long history of discontent regarding art museums. And this discontent could be related to the main promise of the museum: to protect artworks. In response to this promise, people usually think that there is 1.) too much protection for art; and 2.) not enough protection for art. Most often, these two responses become intertwined. Though this may seem paradoxical, the art museum is nonetheless regularly criticized for being simultaneously too protective and not protective enough.

4:00 pm | Jonathas de Andrade and Adrienne Edwards

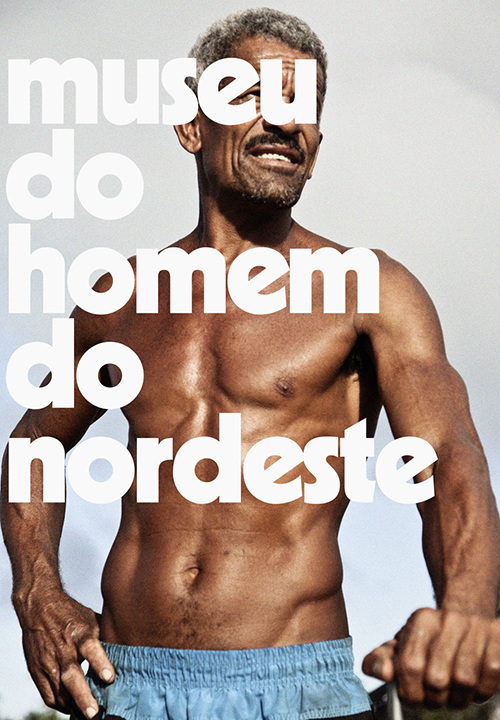

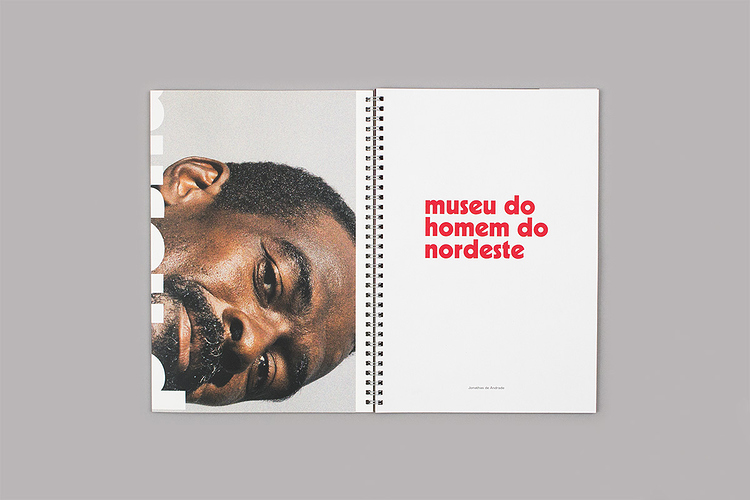

Jonathas de Andrade and Adrienne Edwards discuss the ways his bodies of work interrogate social, economic, and political systems, often through fugitive acts that rely on and articulate the fleeting dimensions of memory, history, mythology, and desire. The conversation focuses on Andrade’s multifaceted project Museu do Homem do Nordeste (Museum of the Northeastern Man; 2013 –), realized as private and chance encounters to create photographic portraits that culminate in a dynamic poster installation to a conceptual and material framework for his recent solo museum exhibition at the Museu de Arte do Rio, in which he redeploys notable marketing tactics such as brand development into art objects. Their dialogue delves into the complicated notion of the Brazilian imaginary as espoused by sociologist Gilbreto Freire, who founded the museum in 1979 for which these artworks are named, as well as authored the seminal text Grande e Senzala (The Master and the Slaves), first published in 1933.

4:45 pm | Hito Steyerl

A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War

A tank on a pedestal. Fumes are rising from the engine. A Soviet battle tank— called IS–3 for Joseph Stalin—is being repurposed by a group of pro–Russian separatists in Konstantinovka, Eastern Ukraine. It is driven off a WWII memorial pedestal and promptly goes to war. According to a local militia, it “attacked a checkpoint in Ulyanovka, Krasnoarmeysk district, resulting in three dead and three wounded on the Ukrainian side, and no losses on our side.”

One might think that the active historical role of a tank would be over once it became part of a historical display. But this pedestal seems to have acted as temporary storage from which the tank could be redeployed directly into battle. Apparently, the way into the museum—or even into history itself—is not a one–way street. Is the museum a garage? An arsenal? Is a monument pedestal actually a military base?

Avant Museology is a two-day symposium copresented by the Walker Art Center, e-flux, and the University of Minnesota Press.

Taking its cue from the recently published book Avant-Garde Museology, the symposium will address the memory machine of the contemporary museum vis-à-vis its relationship to the contemporary artistic practices, sociopolitical contexts, and theoretical legacies that shape and animate it. Where the museum may have once been a mere container for objects and ephemera, the mutability of the contemporary museum has facilitated the apparently seamless absorption of its own complex histories, paradoxical politics, and socioeconomic functions and ideas. It begs the question: can contemporary museology be invested with the energy of the visionary and political projects contained in the works that it circulates and remembers?

The museum of contemporary art might very well be the most advanced recording device ever invented in the history of humankind. It is a place for the storage of historical grievances and the memory of forgotten artistic experiments, social projects, or errant futures. But in late 19th- and early 20th-century Russia, this recording device was undertaken by a number of artists and thinkers as a site for experimentation. Edited by Arseny Zhilyaev, Avant-Garde Museology documents the progressivism of the period, with texts by Alexander Bogdanov, Nikolai Fedorov, Kazimir Malevich, Andrey Platonov, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and many others—several of which are translated into English for the first time. At the center of much of this thought and production is a shared belief in the capacity of art, museums, and public exhibitions to produce an entirely new subject: a better, more evolved human being. And yet, though the early decades of 20th-century Russia have been firmly registered in today’s art history as a time of radical social and artistic change, the uncompromising and often absurd ideas in Avant-Garde Museology appear alien to a contemporary art history that explains suprematism and constructivism in terms of formal abstraction. In fact, these works were part of a far larger project to absolutely instrumentalize art and its rational capacities and apply its forms and spaces to a project of uncompromising progressivism—a total transformation of life by all possible means, whether by designing architecture for life in outer space, developing artistic technology for the resurrection of the dead, or evolving new sensory organs for our bodies.

Today, it is hard to deny the similarity between the bourgeois museum and the contemporary liberal dogmas of open-ended contemplation and abstract self-realization that guide curatorial and museum culture since the dismantling of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. As such, this symposium will launch a further investigation into the militant inclusiveness and delirious pragmatism of the early avant-gardes, shedding light on the social and artistic decisions of a critical period of left-wing politics as well as the ideology of contemporary museological culture more broadly. An explicit question suddenly emerges: under a regime in which social experiments and upheavals become abstract formal gestures, what has the political application of historical memory become?

Perhaps the museum of contemporary art already serves this purpose. Consider what Nikolai Fedorov wrote in 1880s: that the ultimate function of the museum is to unify progressives and conservatives, vitality and death: "And our age in no way dares to imagine that progress itself would ever become the achievement of history, and this grave, this museum, becomes the reconstruction of all of progress’s victims at the time when struggle will be supplanted by accord, and unity in the purpose of reconstruction, only in which parties of progressives and conservatives can be reconciled—parties that have been warring since the beginning of history.”

Avant Museology coincides with the opening of Question the Wall Itself (November 20, 2016–May 21, 2017), an exhibition curated by Walker Art Center Artistic Director Fionn Meade with Jordan Carter, featuring the work of Jonathas de Andrade, Uri Aran, Nina Beier, Marcel Broodthaers, Tom Burr, Alejandro Cesarco, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Theaster Gates, Ull Hohn, Janette Laverrière/Nairy Baghramian, Louise Lawler, Nick Mauss, Park McArthur, Lucy McKenzie, Shahryar Nashat, Walid Raad, Seth Siegelaub, Paul Sietsema, Florine Stettheimer, Rosemarie Trockel, Danh Vo, Cerith Wyn Evans, and Akram Zaatari. Question the Wall Itself runs November 20, 2016–May 21, 2017.