Join Tyler Coburn [@tylercoburn] on this thread for live responses to Friday evening’s presentations during the Avant Museology symposium at the Brooklyn Museum.

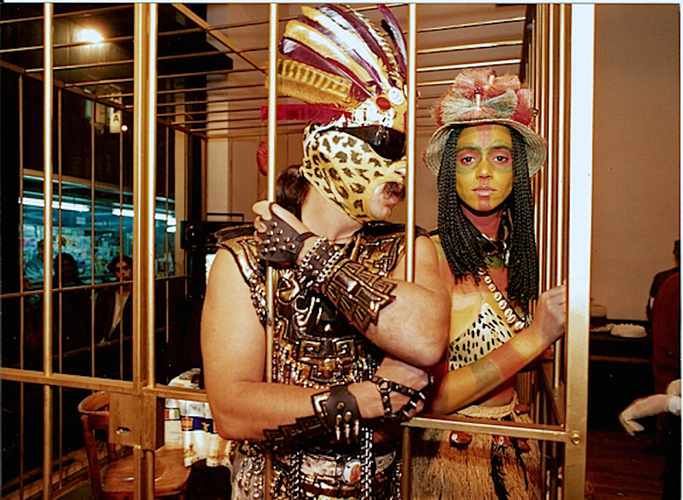

Image: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Buenos Aires, 1994. Photo courtesy Coco Fusco.

Schedule: Friday, November 11, 2016—6pm to 9pm, EST

Live Stream here

6 pm—Symposium opening notes

6:05 pm—Boris Groys

There is a long history of discontent regarding art museums, which could be related to the main promise of the museum: to protect artworks. In response to this promise, people often think that there is either too much, or not enough, protection for art. Most often, these two responses become intertwined. Though this may seem paradoxical, the art museum is nonetheless regularly criticized for being simultaneously too protective and not protective enough.

7 pm—Liam Gillick, Anne Pasternak, and Nancy Spector

Liam Gillick moderates a discussion between Anne Pasternak and Nancy Spector—who are both relatively new to the Brooklyn Museum—about reconciling progressive, community-based projects or collaborative, experimental exhibitions with the reifying effects of a major art museum. Topics include the exhibition theanyspacewhatever at the Guggenheim Museum in 2008, which brought together a group of artists who had worked together and separately since the early 1990s, but who had not yet exhibited collectively within the constructs of an institutional environment. What is lost and what is gained when collaboration is dictated by an organizing entity? Similarly, the question of translation will be applied to many of the itinerant, social practice projects of Creative Time. Is there a space for such outreach in an encyclopedic museum?

7:40 pm—Hans Ulrich Obrist

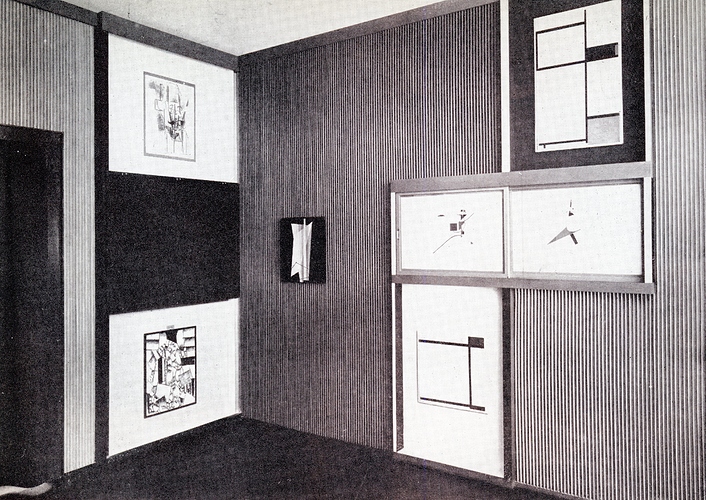

Classical, traditional exhibitions emphasize order and stability. But in our own lives, in our social environments, we see fluctuations and instability, a plethora of choices, and limited predictability. Alexander Dorner, who ran the Hannover Museum in northern Germany in the 1920s, defined the museum as an energy plant, a Kraftwerk. He invited artists such as El Lissitzky to develop new and dynamic displays for what he called the “museum on the move,” where exhibitions would be in a state of permanent construction, and where the viewer could permanently create—and question—his or her own history.

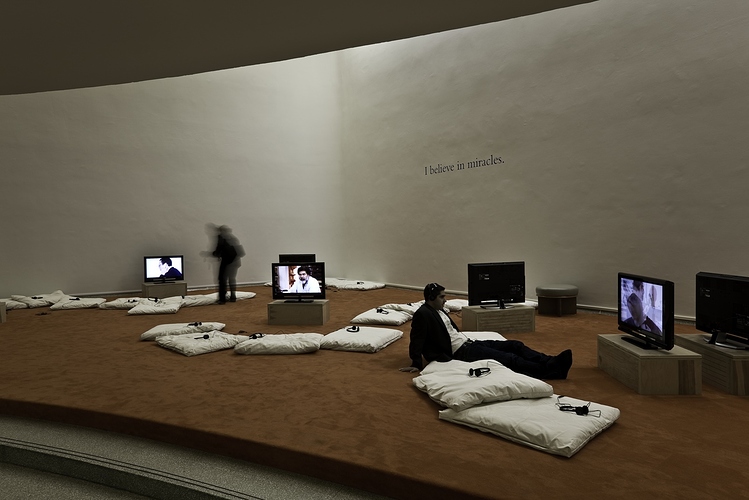

8:20 pm—Anton Vidokle, Immortality and Resurrection for All

Anton Vidokle presents part of a new film based on Russian Cosmist philosopher Nikolai Fedorov’s c. 1880 essay “The Museum, Its Meaning and Mission,” which is included in Avant-Garde Museology. Starring members of the present-day Fedorov Library in Moscow, as well as Arseny Zhilyaev, the film was shot last winter at the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Zoological Museum, the Lenin Library, and the Museum of Revolution. Entitled Immortality and Resurrection for All, the film is an artistic interpretation of Fedorov’s universal museum, where immortality and resurrection will be actualized.

The event is currently at capacity; for those unable to join in person, the evening will be streaming live here

For more information on the Avant Museology symposia at the Brooklyn Museum and Walker Art Center: visit this page