August 2020

Conversation with Dawn Paley, in collaboration with Enrique Arriaga (editing and sound effects) and Kevin E. Hernández Martínez (transcription)

[Links to soundcloud audio files at the bottom]

THE NEOLIBERAL WAR OF MASS DISAPPEARANCE BEHIND THE SO-CALLED “THE WAR AGAINST DRUGS”

Conversation with Dawn Paley

August 2020

Irmgard: Today I’ve invited Dawn Paley to discuss her new book “Neoliberal War: Disappearance and Search in the North of Mexico”, which just came out with Libertad bajo palabra. Dawn Paley is a brilliant thinker and journalist, one of the best, I think, and I’m grateful that we have her working in Mexico. She’s originally from Vancouver, BC, or Occupied Musqueam, Skwxwú7mesh, and Tsleil Waututh Territories, in Canada. She’s been based in Mexico since 2011, her first book is titled “Drug War Capitalism”, and it was released in 2014 with AK Press, and it was one of the key books to understand what is known as the “War against drugs” in Mexico, with amazing research on the ground. And, also, Dawn has a PhD in Sociology from the Autonomous University of Puebla, Mexico, where one of the most interesting research and dialogue groups in academia, but also linked to political activism, is grounded right now. And, she has an opinion column at the prestigious Mexican leftist newspaper La Jornada. So, it’s really a pleasure and a privilege to have this conversation with you, Dawn, thanks for saying yes.

Dawn, in your new book, you argue that we are trapped in a situation in which we cannot signify what is going on, what we’re going through, and what the country, at large, is going through, in Mexico, is an epidemic of disappearance and violence. That we’re really not understanding what is going on in cities, regions or countries where disappearance of a loved one is almost a rule, and when this happens, a family’s everyday is destroyed. As you argue, Dawn, what is left behind is a void, anxiety, endless pain, of not finding the absent loved one. So, in this book, you take on the task to explain how the situation is currently beyond our grasp. And I wanted you to start with how we have been misled by our historical-political framework to understand this forced disappearance and violence that is happening around the country right now.

Dawn: Sure, well, thank you so much for inviting me to be here, I’m super happy to have this exchange with you. So, my first book, “Drug War Capitalism”, sometimes I think about it as being a little bit like the “Why”’ of the so-called “War on drugs”, though making the argument that it doesn’t just have to do with greedy men and guns, and briefcases full of cash, but that it also has to do with the so-called “legal economy,” with the expansion of capitalism, with the expansion of extractive industries, control of labor, etc.; and in this new project, “Neoliberal War”, I start to think of it more as the “How?”, so I’m looking a little bit less at, sort of, the economic motivations and working more on what’s actually happening on the ground, how are people who are living through this violence describing what’s taking place, how is the state describing it, how are the media, how are the journalists describing it, and how do we as social activist, revolutionaries, people devoted to changing the situation of such deep injustice, how are we describing it. So yeah, since 2006, Mexico has been in a so-called “War on drugs”, I mean, it predates that with all different US-backed anti-drugs programs basically since the 70s, here in Mexico and all over Latin America and different places in the world, but here in Mexico it was a big uptake in military spending and militarization during the presidency of Felipe Calderón, which continued through the presidency of Peña Nieto, and I would argue continues to this day. And so, what I kind of wanted to do with this new book is look really into that, the production of confusion as a key plank, or as a key strategy, because what we’re constantly told from all different sort of [?] #0:04:36.7# power is whether the Attorney General’s Office, Nationally, Federally or on a state level, or you’re going by city or municipal police in different places, is that they’re fighting crime, you know, the army is fighting crime, the National Guard is fighting crime. Criminals, drug dealers, drug traffickers, people who wanna harm your children, you know, it’s a very moralistic type of language. And it’s not just Mexico, you know, in “Drug War Capitalism” I wrote about Honduras and Guatemala, and Colombia as well, it’s happening far beyond as well. But yeah, I mean, really just looking at how people are living this on the ground, and then what the numbers are telling us, which is that… in Mexico, living through a period of unprecedented violence since, basically, the early 20th century, and they’re having a whole bunch of clandestine mass graves all around the country, and by a whole bunch I mean like there’s thousands of them, and like… extermination grounds where people are being, where bodies are being destroyed… This is not normal, this is not like a crime problem, so that’s kind of like where some of that digging started, working with… literally digging, actually, working with family members of the disappeared in Torreón, Coahuila, who are doing these searches and listening to how they’re talking about what they lived through when the so-called “War on drugs” was really bad there and… just trying to kind of… seed or thread through a proposal towards a new understanding, so that we don’t just assume that what we’re living through is a series of “bad apples”, or a series of policy mistakes, or a series of… victims caught in a crossfire, all these types of arguments that contribute to the depoliticization of what I consider to be a war on the people of Mexico.

I: So, could be talk about systemic, or systematic, genocide?

D: I use the word “Holocaust” in the book because of the root etymology of Holocaust, which is “all burnt”, because of how they’re finding human remains in that area, and in other areas of Mexico, and I use it in a comparative sense in terms of really thinking through just how many, potentially thousands, tens of thousands of people… and then we can get more specific, to an extent, even though there’s a huge problem of statistics, of the collection of statistics in these kinds of crimes, specially disappearance, but… targeted specifically towards young men, in poor, working-class parts of geographical areas of certain cities, being targeted for extermination and social cleansing.

I: And, Dawn, the people that live this in the flesh, would you say that they buy the framework of the “War against drugs”? Or they live it differently?

D: That’s an interesting question, I think we’re so bombarded by the state and media discourse, and we’re bombarded beyond just the newspapers and, you know, what we’re reading in terms of information: were bombarded by Netflix, and we’re bombarded by series, supposedly about “narcos”; bombarded by all these narratives telling us constantly that what’s taking place in Mexico is a war between drug cartels and the Mexican state. But yeah, there’s a few interviews that I did that always stuck out to me, where I’d say, well, “What did you see? What can you actually describe, like, what you saw?”, you know, in the case of one woman who is an eye witness of the disappearance of her son, for example. And she told me that, you know, it was a white pick-up truck, and then I kind of pushed her on, she said, “You know, they said they were Los Zetas”. And I was like, “Well, what did you see, though? What is your experience living in that colonia?.” And she eventually just said, “You know what? They were all driving white pick-ups with no license plates. The Attorney Generals, state Attorney Generals, police officers, the state police, and so-called “organized crime groups,” they’re all driving the same trucks. So, actually, I’m not actually sure who were the perpetrators,” right? And I found that to be a repeated thing, people who were living on the ground… there’s definitely… I know this myself from being a journalist, when you’re in a news room, you take the police an the Ministerio Público’s word as gold, like it’s not questioned, whatever the police say, that version goes in and then, if you have time, you get a second version, right? So, a lot of the narratives we find in the newspapers, local newspaper included, like in Torreón or Gómez Palacio, Durango, which is a city next door, they would say “This is the Chapos fighting the Zetas”, and they… title [?] always be coming basically from the police as the main source, and I kind of looked at this a little bit in “Drug War Capitalism” too. And that’s very influential, I mean, it’s on all the TV stations, it’s like… that’s the vernacular that we have to talk about what’s going on. And I think it allows victims to be criminalized over and over again by saying, you know, “They were involved in the drug trade”, “They were using drugs,” whatever. And it’s hard, it takes an effort for folks who are directly experiencing this to step back and reject that discourse, push back against that discourse, ‘cause there is still that discourse of innocence, where people want to say, “My son was innocent, my son wasn’t doing anything,” but some victims have stopped doing that, and say, “So what if he was involved? Does it matter that he was… Should he have been disappeared?” Obviously the answer there is no. So, there’s definitely hard pushback on the criminalization piece, and then, in terms of the cartel, the family members, what they do know is the extent to which the authorities are often involved directly in the disappearances, the extent to which they know who the perpetrators are, the extent to which they have existing relationships with perpetrators. You know, the victims, the family members of people who have disappeared, they know so much about how intertwined the state is, the state armed like… the police, specially, but the army, the marines, etcetera; they know how intertwined those official agents area with so-called “organized criminal groups,” which I prefer to call “paramilitaries.” They definitely know that, but, yeah, untangling it all is… I mean, it’s confusing for me.

Irmgard: That’s really important that we talk about that, how we need to untangle this confusion, which you were saying, this confusion comes from the families living some facts in their flesh and the gap that comes between their lived experience and what we know of the violence that is stated officially in the media, by the state through the media, right? And this is where this confusion resides, and this is why it’s so complex to untangle all this violence, right? You just talked about how the state is involved, state authorities, municipal authorities, are involved in this forced disappearances and how the victims know their perpetrators and so on, and they know who they are. And you’re talking about… in your book you develop this really important concept that is expanded counter insurgency, and you use it to describe contemporary forms of state violence, and I wanted you to explain that a bit more.

D: Sure, so… I studied a lot a counterinsurgency theory to try to understand what’s happening in Mexico, and just a lot of things it didn’t just quite fit, so I do think that the violence that we’re experiencing in Mexico is definitely informed by Cold War models, and there’s definitely a transmission of information, of repressive repertoires through different generations. Greg Grandin documents that in his book called “Empire’s Workshop”, where he writes about how the same clique of officials go from coordinating the US war in Vietnam, to coordinating the US war in Central America in the 80s. So, we know that there is a transmission of information through these different conflicts and through this different kind of eras or generations. But just counterinsurgency just didn’t quite work for Mexico, because I think… You know, Hillary Clinton came to Mexico when she was Secretary of State, and she suggested that the cartels are insurgent groups. And so, that suggests that, if you have counter insurgency in Mexico, that the insurgents are drug cartels… which does not match up with lived reality. Lived reality here is that people, poor people, in towns and cities in Mexico are being persecuted, are being picked up, are being IDed, are being held in casas de seguridad, and taken to jails by both or a multitude of state groups and [non-state] armed groups. And I heard this over and over again in Torreón. They’ll pick up young men, and the young men won’t know whether it’s a drug cartel picking them up, or whether it’s the state police picking them up, there’s no identifiers. And they’ll pick them up and the questions will be the same: “What are you doing? Where is your ID? What are you doing in this part of town?”, you know, this type of questioning, and so… That’s where it’s like… there’s a real confusion in terms of who the actors are right now, but also who the insurgents are, because it’s not clear in Mexico, we don’t have a kind of a group like the FARC in Colombia, or the ELN, or some kind of visible organized powerful insurgency group that actually wants to overthrow the state. And I think that’s part of why there’s no argument to be made that cartels are insurgent groups, they’re paramilitary groups, they work hand in hand with the state, they have no interest in taking the state over, they’ve actually like augmented state power, right? So, we have that sort of confusion of perpetrators, but we also have a sort of lack of a real insurgency, which is where, just looking really specifically the case of Torreón, but I think more probably in Mexico, you can really see that people at large are being treated as insurgents, because the few times that we get to hear who the victims are of this massacres and mass killings in Mexico, or mass disappearances… I’ve actually learned a little bit about the biographies: often people who work in the popular sector, who work in informal commerce, who are migrants, who are people who are traveling, construction workers going to work from one town or one city to another…huge parts of their lives are connected to informal economies, which I think actually are incredibly powerful and actually can get people a lot more dignity, a lot of times, than working in massive, super transnational corporations, and so on. The Mexican people, at large, are considered insurgents, and specifically people, which is the majority of the population, who are connected to informal economic activity.

I: Okay, so, the target is being working-class people who are, what I would say, redundant populations, not the poor, idealized by the current regime, but the people who are really outside of the networks of consumption and production.

D: Or they’re in alternative networks, right? So, I don’t know, I was thinking of, I mean, there’s also been killings of maquila [sweatshop] workers, so there’s definitely an element of labor discipline in the violence in Mexico, but there’s also an element of… sort of a notion of a disposable population on the part of the state, of people who like… don’t pay taxes, and who aren’t on payrolls, who work more on like day-to-day, and who participate in alternative economic structures that, again, not to like over-glorify them, or to say that they’re always good, but that can allow people to have a certain amount of dignity and not become total wage laborers, getting completely exploited. Because those people are also victims, right? I mean, basically, it’s like the majority of the population in Mexico, which is, again, today the same people who are super exposed to COVID. I mean, it’s a perfect overlap.

I: But these are also people who live on lands rich in “natural resources”, quote unquote, or who live on lands that are desirable for agroindustry, and so on?

D: Right, that’s kind of what I developed in “Drug War Capitalism”, for sure, I was looking more at territory, and the case of Torreón is really different: what you see in Torreón is basically the maquila [sweatshop] industry… you know, it’s highly urban, because there’s not enough water for people to live a dignified life as agriculturalists in ejidos, ‘cause there’s so many ejidos, collectively owned lands, around Torreón, but the maquila industry basically pushed a huge urbanization in the 90s, and when the maquila sector collapsed, it collapsed like four years before the “drug war” started. So, it was like hundreds of thousands of workers became redundant. I take a lot of inspiration from the work of Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who wrote “Golden Gulag”, and she talks about prisons coming in and serving that purpose, right? in the Imperial Valley of California, and the hypothesis that I’m working on here is that, rather than prisons and prison-industrial complex coming into Mexico, what we saw was this massive, massive wave of enforced disappearance and massacre, as a way to tighten the screws on these communities, undo the social cohesion, their ability to resist. And here I’m not talking necessarily about resource-rich areas, we’re talking about social contention, like containment of populations through extreme violence.

I: So, would you say Torreón is the new Juárez? What Juárez was in 2010?

D: Yeah, so in Torreón it started 2008, and the height of the violence is in 2012, and it’s kind of been descending since then. I think that Juarez is part of a constellation that includes Torreón and includes many other cities that we never talk about. And part of the reason I wanted to work in Torreón, because I met “Grupo Vida” and I thought they seemed awesome because they are an autonomous group of like self-organized family members searching for people who are disappeared, but also because I wanted to work in a city that wasn’t so like… Juárez is it still so messed up to this day, right? It’s not over in Juárez, I feel like we need to really, we need to amplify the discussion of what’s happening in all these secondary cities and smaller cities, you know Torreón also is not directly on the border, even though it acts like a border city, and it’s a place, you know, when I started working there people were like: “You want to do research here?” And I think, like Torreón, there’s many other places, you know, there’s the famous ones, that people… “Okay, yeah, Culiacán and Ciudad Juárez”, and then there’s just so many others, where it’s just been like a nightmare for people over the last 15 years that it doesn’t transcend, it doesn’t actually um… The news doesn’t even get to like… the state capital, much less to Mexico City, much less international, right? So there’s tons of people [inaudible] that are just suffering really intense violence and it just… no one no one really finds out about it, it doesn’t really travel or make the national news media, unless it’s an extremely radical event, right?

I: Right, so you’re saying, uh, people at large but meaning working class who work in precarious conditions, who were not taxpayers, who were not part of the payroll, they are being treated as insurgents, no? And they’re also migrants, construction workers, and so on and so forth; they’re being treated as criminals, sorry, as insurgents, but they are being labeled as criminals, so insurgent is a label that comes from the Cold War, right? Rhetoric and criminals comes from the rhetoric of the Drug War. Can you talk a little bit about that slippage between both concepts and both temporary frameworks to describe the social historical confusion, the historical conditions? Which I think add to the confusion even more.

D: Right, yes, I mean, it’s so confusing and it’s, yeah… I mean, the number one predictor for whether or not someone is disappeared or not is what neighborhood they’re in, or what colonia they live in, that’s the number one predictor, the second is age and the third is gender, right? So it’s like, there are some things we can say about who’s being disappeared, but it’s not in the old language of trade unionists and activists, and like visible social leaders; although that is also happening, that’s not the main dynamic that’s taking place. I think the term insurgent predates the Cold War, I think it’s from the French, you know, the resistance in Algeria, I think is partly where that first came into use, and what was your question about the slippage…?

I: Yeah, there’s this slippage people are being labeled or treated rather as insurgents and prosecuted as insurgents, but they are being labeled as criminals.

D: The criminals are the perpetrators of what’s taking place, right? Which is mostly the state, and it’s mostly the state forces, the official state forces, and, you know, former state forces, retired state forces working hand in hand with active duty, military police, whatever. And I don’t necessarily think that, you know, all of the folks are insurgents either, like I think they’re being treated as insurgents, I think they’re people who are going about daily life within a community popular framework of production and consumption, and extended family care, and neighborhood networks and different kinds of sort of social organization, that also Ruth Wilson Gilmore talks about, right? In “Golden Gulag”, folks who are participating in these different networks are being treated as insurgents, they’re not, they’re not, it’s not an insurgency. However, I do think that from power, from the height of power in Mexico and in Washington, these types of social formations are read as a threat to the maintenance of the ever increasing inequality, the ever worse conditions of labor, the ever, you know, everything getting more austerity, like we’re seeing now in all different aspects of life, really also wanting to prevent people from migrating, because I see War on Drugs also as being a strategy to try to prevent people from transiting through Mexico, be they Mexican or non-Mexican, to reach the United States, which acted for a long time as a sort of way to keep Mexico kind of under control, keep people eating, for the so many migrants who go to the United States, all of these, you know… The majority of people in Mexico, are completely vulnerable, but i refuse to think—I refuse to use a discourse that talks about them as criminals, and that considers innocence as if someone innocent was killed, it was by mistake, because that suggests…

I: Collateral damage

D: Exactly, it suggests that there’s some kind of real planning and real intelligence that’s being used to eliminate so many people, I mean, we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people between disappeared and people who’ve been murdered since 2006 in the context of this War on Drugs, right?

I: Dawn, it’s so overwhelming.

D: I know.

I: Like… I’ve read you, your two books and I’ve thought about it, and I’ve written about it, and now you’re telling it to me again here, I’m like really overwhelmed. So you’re saying… you’ve discovered that cartels are paramilitary groups that are augmented state power.

D: I think so, yeah.

I: So, we’re living a form of state violence with no real insurgency, violence for violence’s sake, or violence for the sake of capitalism, I’m hoping you go into that later on, but right now I want to go back to that concept you developed that you call “expanded counter insurgency”.

D: Sure, so, yeah, I kind of try to break it down into three pieces, so there’s a confusion of perpetrators, right? So, they’re constantly telling us that they’re going after the bad guys, right? The drug cartels. Being on the ground, as if it’s actually the state and the so-called “drug cartels” that are together carrying out a war on the people, on the popular sectors, on the neighborhoods, just like what we were just talking about, right? So that huge confusion in terms of who’s doing the violence. We’ve got an expansion of the idea of insurgency, so there’s like no actual armed insurgency necessary in order to treat the entire population like insurgents, again because they are participating in these community popular life ways, right? That can be outside of the sort of transnational circulation of capital. And then the last element is the use of a whole continuum of violence, and I call it a complex of violence basically, complejo de violencia, that ranges from, like, the brutal exhibition of bodies to their complete disappearance. So I just wanted to clarify that expanded counter insurgency is what I think the state is doing, right? It’s not a general analysis of everything that’s taking place, it’s, I think, the state approach to the war, and that’s why I think “Neoliberal War”, this book, is more about the “How?” It’s a form of counter-insurgency that the state is doing against the people. I hope that makes it clearer.

I: No, that that makes it perfectly clear, but let me just go back a little bit. So the “War against drugs”, you argue that it’s a form of expanded counterinsurgency in which paramilitary groups, and these are state or non-state agents, we’re confused between them, they perpetrate crimes against vulnerable populations throughout Mexico, and the result of that is that these crimes are giving the state and corporations power through social cleansing, but you’re arguing that the state and corporations are having more power, but then in recent years and under Peña Nieto, in the media, people started talking about the concept of the “failed state”, by which they meant that neoliberalism had hollowed the state out to the point that the state didn’t have full sovereignty over the country, and that is something—or regaining that sovereignty should be the task of the “War against drugs”, but, how…?, you know, can the official propaganda, that the Mexican state is a failed state, be compared against this factual reality in which these murders are giving the state and corporations even more power?

D: Right, I mean, there’s a bunch of, I think, mis- or, like, inaccurate assumptions in what you just described, right? As a position, so, I think that Mexico is not… so, yeah, there’s so many ways to approach this, right? There is the idea that a state is supposed to look after its people, which I think, if we look in many states over the history of the last few hundred years, there’s not that many examples of that actually being the case, but that’s still like what we are led to believe through all of the kind of education that we receive and we’re all inculcated with since the time we were born, right?

That’s what a state is supposed to do, and so the idea is that a failed state is somehow not able to not only look after its people but, as you said, that doesn’t have sovereignty, etc. The thing is that Mexico is clearly a state that is failing its people, but I actually think that we’re seeing that all over the world right now, like with COVID so clearly, there are very few states that are actually managing to mitigate the extent that huge amounts of people aren’t super exposed and vulnerable right now, and they’re always the same folks who are—they’re not vulnerable, they’re made vulnerable, right? Through economic policy, through political policy.

The failed state label also suggests that, you know, private property is at risk or that it’s a country where you can’t do business, so the suggestion that Mexico is a failed state completely ignores the fact that Mexico continues to be ranked like, in terms of macroeconomics, like among the most stable countries, and it’s like a model nation according to, like, the World Bank and the IMF, it’s considered a very secure place to do business, it’s considered a secure place for transnational corporations to come and mine, and build infrastructure, and build tourist infrastructure, and where private property, especially when owned by these transnational interests, is totally protected by the state, right? So, is Mexico’s state failing its people? Yes. Are most states failing their people? Yes. Is Mexico totally overwhelmed by drug violence? No. Is Mexico extremely violent because, far from becoming hollowed out during the last 12 years of neoliberalism, it’s actually become hyper-militarized, and the military budget has increased, and the police budget has increased, and the security budget has increased? Yes, right? Like, so that’s where the idea of “Neoliberal War” comes from, you know?, wanting to say militarization is a centerpiece of neoliberalism: it’s absolutely essential…

I: And the failed state…

D: I think the failed state is a bit of a straw man.

I: And, Dawn, you’re saying that this pattern can be seen all over the world and throughout Mexico. What do these territorial patterns of militarization and violence tell us about the goal of this social cleansing going on?

D: I mean, in Mexico, it’s just—what we’ve seen in Mexico is a war that is so complex in the sense that it looks really different in a city like Juárez, or in a place like Torreón, than it does in a place like Chilapa, Guerrero, or Ostula, Michoacán. There’s so many different variants, but it’s variants on a theme, which is militarization through official forces and paramilitarization through a whole different, like, a host of mechanisms including former soldiers, retired soldiers defected soldiers, and police officers; soldiers and police officers who are participating in both paramilitary activity and, like, legal armed force activity, and then independent contractors, and like so-called sicarios [hit men]; like, there’s so many different kind of layers, but I don’t wanna—it’s not like it’s all being controlled from Washington, that is totally not the argument I’m making, but there’s—it just seems like there is a certain—there are certain outcomes from this kind of militarization, where you’re specifically militarizing on the pretext of stopping the flow of illegal narcotics, which is something that the armed forces can easily plant, can easily say, “Look, we’ve got it,” you know, “we’ve found the drugs,” like it’s an inanimate object that can appear wherever they want to.

It’s a very powerful pretext for what I actually think are campaigns of, yeah, displacement, forced displacement, and again, just to come back to the idea of vulnerable people, I mean, I think that people are made vulnerable by these systems, but I also think that these systems go after people who are organized to a certain extent; for example, you know, in Torreón, a lot of people would talk to me about how the first people that were disappeared, that were murdered, in Torreón, when the crime really started, when the militarization—because that’s the thing, like, the militarization started at the same time as the crime started, right? So, it’s like, it’s clearly something that connects with the other, they’re not two separate phenomena, it’s not like there was a crime wave in Torreón, and then Torreón was militarized, both happened like lockstep at the same time, whereas, like, clearly the presence of all of these police and soldiers is provoking chaos within, an already established, generations long, network of informal commerce and smuggling, and so on. The people, what they would say to me, was that the first people that started to go missing or that were killed were the teenagers that would gather on the corners, and they would sit outside a shop and like, basically, watch who was coming in and out of the colonias, and in that way were providing kind of a security role where they were living and, you know, there’s an argument to be made that they were, like, very easily co-opted by different crime groups or by the police, by different groups of police or whatever; but there’s an extent to which it’s also, yeah, like, I wouldn’t want to just read it as attacking vulnerability, I also want to read it as attacking any level of organization, community organization that exists open, community organization.

I: That’s what I want to get at in the next questions, we’re talking about fear as a form of control? You mentioned a form of “labor discipline” or violence as a way to discipline workers, and also to discipline gender, no? And I’m going to ask you to talk a bit later about the text you co-wrote with Raquel Gutiérrez on violence and gender, but you mentioned also that we have seen this pattern of violence in Ostula, in Michoacán, and Ostula is known for having their own community police, for having kicked out the talamontes, right? A few years back, and of kicking out old state authorities present in the village, so it’s not only semi-urbanized or urbanized populations that are incorporated to precarious forms of labor, maquiladoras, or migrants, but also communities who live with dignity, and who are outside the cycles of capitalism.

D: Absolutely.

I: So, can you talk about that a little bit?

D: I mean, I would just say, again, it’s just, it speaks of the flexibility of the discourse: you can plant drugs anywhere you can, accuse anyone of being a criminal, of being a drug trafficker, there’s no further proof needed, the system just constantly self-justifies by saying “Drug trafficking, drug trafficking, drug trafficking,” sending in the military to get the drug traffickers; I mean what the people of Ostula lived was a campaign of paramilitary and military terror against their leadership. But, you know, the doubt was always being sown: that it was a trafficking route, that they were, you know, there was illegal activity happening, and like, just like salt and pepper that discourse into any repression is enough to make people in Mexico City go, “Oh yeah, I guess they must have been, you know, criminals,” or people outside of Mexico, or whatever; like it’s just constantly sowing the seeds of doubt, and I mean, they unbelievably did it with Ayotzinapa, you know, trying to suggest that the, you know, the 43 students, that someone would be involved in drug trafficking, and that was why it all happened, and there was actually criminals, like, infiltrated within the—it’s unbelievable when you actually start to look at it, that it still works and it’s still accepted as kind of, “I guess they had it coming,” you know, “I guess… too bad for the innocent ones but, you know, some of those kids knew that they were…”. Like, it’s, it’s a very, very flexible and extremely useful discourse from power, because, I mean, they can use it to get away with anything, and that’s what we’re seeing. I mean, thousands of mass graves around the country? It’s… and still saying it’s a fight against crime, when I initially started this project, I wanted to work on mass graves, because it just was like… there is no way that this can actually be a fight on crime, and you can have thousands of mass graves, it just—it doesn’t work. Mass graves tell us that we’re in a different… in a war, like, mass graves are a clear signal that something else is happening, and then, you know, once I started working on this project, and then the 43 students, were disappeared, and the search groups started to come out, and then my focus kind of shifted towards that, towards that search, and that form of resistance that these family members are using to look for their loved ones.

I: And so, the groups are going to expand, no? With the outsourcing of migration control from the US to Mexico, and with the increase of migrant caravans, and they’re being stuck in Mexico, and the new Guardia Nacional military station, no?

D: I mean, I think we don’t have any idea… For example, like what would have been a responsible thing to do at the beginning of López Obrador’s presidency would have been to actually try to actually get a real scope on what’s taken place in the last 12 years, so one way to do that, for example, would have been to have a census question, because they’re just doing the census right now, a census question on disappearance, a census question on violence, a census question on homicide, so that we could actually start to get real statistical numbers and information, that would give us an idea of the scope, because, right now, Mexican state is talking about a few thousand mass graves. It’s definitely way more, right now the Mexican state is talking about 70 000 people disappeared since 2006, and we know there’s a massive under count because people are terrified to go report these disappearances to the same authorities that they know are essentially connected to those who are responsible for them, —so there’s a there’s a universe of crimes, of extremely serious crimes, often perpetrated by the state, or done under the supervision of the state, or, at the very least, done with the complicity of the state, that we have no information about, so we actually don’t know the full extent. There’s so many people still suffering in silence and fear right now, that haven’t come forward, that aren’t working in activist collectives and so on, and so, you know, any numbers we’re operating on are super low and, I mean, I have to say it, it feels like they’re doing the same thing with COVID in Mexico, it’s just minimizing the numbers, blaming the people who are dying for having unhealthy practices, and unhealthy lifestyles, and purposely under counting, so that they can also wash their hands of just, like, yeah; an amount of crime where like, if we had the real numbers in Mexico, I’m confident that things would be upside down, that we would not be living in this situation, people would have risen up, it’s way more severe than it seems, and it already is so bad, right? According to the official statistics.

I: One point I want to make an emphasis of is how autonomy and sustainability, and, that is, the communities who are able to live an autonomous and dignified life, as do many Indigenous communities across the country, are a threat, so non-capitalist life ways are directly a threat and target of the drug—of the neoliberal war.

D: I think the most straightforward way of reading that is that they are a threat because they defend their land, and their land is desired for a wind energy project, for a dam, for… not just like thinking classically extractive industries, but of course those too as well, right? So, mining, oil, and gas; in that sense, they become obstacles, essentially, to the never-ending expansion of capitalism, and I think that community formations in urban areas can also be seen as a threat, I mean, I think it’s just important to go back to 2006 when this started, which I think is a year of heightened social mobilization in Mexico, where people felt like a lot of things were becoming possible, like something new could open in Mexico. In terms of social struggles you had Atenco, you had Oaxaca, La otra campaña, you had the election and the protests for López Obrador, and the fraud that happened in that election, and then in December of that year, you had the announcement that the drug war was basically on, even though Felipe Calderón did not campaign on that at all, was not part of his 2006 campaign, and then by December, he was sending troops into Michoacán, right? A historically and, to this day, Indigenous state which is very, very rich in resources.

I: So, we could say that the Neoliberal war began with the uprisings in 2005-2006, with the Drug war declared by Felipe Calderón?

D: I use Neoliberal war to just challenge the idea that we have to keep using terms and ideas from the Cold War, to talk about what’s happening today, but also to challenge the idea that after the Cold War we somehow entered into a time of peace, which is kind of, I feel, what is, suggested by the end of the cold war, and the lack of any kind of term or sort of narrative that helps us understand that—and it’s not just in Mexico, but in all these disparate nations, and I mostly look at Latin America; you actually have intense fighting and violence to levels, not always, but often, that are worse than what happened during the Cold War conflicts, and this is true, for example, in El Salvador or Honduras, in terms of the number of disappeared, which is higher now than it was during the internal conflicts, so Neoliberal war is something basically that, when the Cold War is winding down, the hawks are looking for a way to keep the military machine going, and it’s the Drug War, but depoliticizing that, because another piece of the Neoliberal war that’s really important and it’s part of the confusion is that it’s totally depoliticized, right? So, we’re supposed to think the victims are criminals, we’re supposed to think that the good guys are the state, we’re supposed to think that the drug cartels have more power than the government, and that they’re trying to take over the state so that the state can’t help people, so then we have to support the government and etc., because the other choice is, like, living under the reign of the cartels and so on, and it’s like this is actually, again, I think, expanded counter insurgency, right? It’s a state strategy to manage this level of inequality that we now live in, which is, like, unbelievable.

I: And, Dawn, it’s also Neoliberal war because we need to emphasize again and again that militarization is an essential component of neoliberalism.

D: Exactly, exactly. So the Drug war, or the War on crime, or—these are the sort of discourses that the state is using to talk about what they’re doing, and instead of using those, I’m trying to use expanded counter insurgency: that’s what the state is doing, they’re calling it a Drug war, they’re calling it a War on crime but, again, my work is like really trying to, yes, do some discourse analysis and stuff, and say “What are they saying?” But really, like, from on the ground, what is it that people are experiencing, like, what is actually happening, and from, like a pinhole of, like, working in Torreón, Coahuila, but really trying to think through, like, how can we think this stuff through on a broader level that helps us politicize what’s happening right now, that gives us a new set of tools to talk about what we’re living through that doesn’t criminalize victims, that doesn’t automatically make… like things like failed state, it makes the automatic response be, “Well, we need a stronger state then,” or, “We need more police then, we need more military,” or, “We need more…”, like constantly going back to the old arguments, the punitive state-centric arguments for how we get out of this situation; trying to give ourselves like a new toolbox that allows us to see, like, this is political, this is war on the people, it’s connected to an economic system, it works within an economic system, it obviously does not threaten this economic system.

I: But the myth of the drug war is so powerful. I mean, first time I read about this new wave of state violence under Neoliberalism was Pilar Calveiro, then your book came out, Oswaldo Zavala, Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, but it still seems not to reach the mainstream, because the drug war myth is so powerful, and to an extent, films Netflix, the arts, literature, have been feeding on to this myth, no? That’s so dangerous, and we need to break through it.

D: Exactly, I mean, unfortunately the counter narrative, which is something that we’ve been working on with, like, lots of colleagues, including tons of activists as well, not just writers and journalists, but it’s far from hegemonic. And it’s, like, super complicated, right? Because if we’re going to go outside of that, of the state framework and the state discourse, it’s like you have to explain the whole universe, you know what I mean? It’s like… it’s not… conceptually, it’s extremely complex, but the idea is, Neoliberal war is really like, for me, it was like to say, “Let’s think about this period we’re living through as not just a bunch of random homicides, and a bunch of, you know, people caught in the crossfire, and a bunch of bad guys getting killed by good guys, let’s think about this within the context of capital, let’s think about this within the context of migration, let’s think about this within the context of territory,” and that’s where we can start seeing like, “Oh this is actually working out pretty good for the maintenance of an extremely unequal system, yeah.

I: And… no, what makes it also super hard to break through this myth is that, even the people who live it in the flesh are confused, and I want to conclude asking you to talk a bit about your work with Grupo Vida in Torreón and their means to resist this Neoliberal war.

D: Sure, so Grupo Vida was founded in 2014, and after Ayotzinapa, as you know, groups, local groups started looking for bodies, and they started finding bodies of people who’d been disappeared who actually weren’t the students, but it was the first time that there was sort of a lot of attention on clandestine mass graves that were being found on purpose by people who were going to look for them, right?

Because we did have the events of San Fernando, Tamaulipas, right?, with 72 migrants and then over 100 Mexicans found in clandestine graves there in years prior, and so on. But the Ayotzinapa searches inspired the family members of Grupo Vida to start doing their own searches, and so, in January of 2015, and these are self-organized family members, most of them are domestic workers, folks who are extremely precarious, and some of them were actually… refused, they were not welcomed into one of the other groups of disappeared because there was a suspicion that the disappeared that they were looking for were somehow involved in drug trafficking, which, again, can be read just as complete… it’s a class thing, it’s nothing other than saying they’re lower class people, or poor people, who may have had connection with smuggling or trafficking, which is very common in border areas, right?, in Mexico.

And so, Grupo Vida starts doing these weekly searches, and they began turning up just tons of fragments, bone fragments, they found a couple of cadavers, but it’s mostly all bodies that have been broken down and burned, and they’re finding bone fragments, and they’re sending them for genetic testing, and they have managed to return some bodies home to their families, and to identify some people who have been disappeared, and they’ve also managed to, through that concrete work, create a really powerful community; they do transcend in the media, because one of the things with disappearance is there’s nothing, there, there’s no story, there’s nothing to talk about, and so family members of the disappeared have kind of like two days a year where they’re sanctified to appear, which is mother’s day in Mexico, and which is the international day of enforced disappearance in August, and this, with them constantly finding these human remains and showing that the government is not investigating, and not looking, and it’s the families that are doing it, and it’s the families that are leading it, it’s a way of totally shaming the state as well, changed the media cycle, right?

It made the media look at what’s taking place and continue to talk about the violence in Torreón, whereas, without the searches, it would have been easy to just be like, “Well, that happened and it’s over, and hopefully you didn’t know anyone that got killed; well, moving right along,” you know what I mean? So, what they’re doing is actually building memory, and yeah, to see the importance of concrete work of them getting together, and doing that work, and of course the priority is always finding someone who’s been disappeared, and it’s so sophisticated the way they sort of manage one of the central contradictions, which is actually something that divided the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, which was that idea that you should only look for the disappeared alive, right?, and then another group that said, “Well, we’re going to look for remains as well,” and some groups in Mexico still refuse to sort of accept the idea that you should look for human remains, although I think it’s becoming more and more accepted, for sure, but, I mean…

I: It becomes a form of mourning the loss, no?

D: The way that they, that these family members that I interviewed managed to sort of assimilate that contradiction is by saying, “I’m looking for someone who can’t look, so I’m still looking for my own child alive, and I’m still confident that I’m going to find my child alive, but I’m also looking because I know there’s all these human remains, and I’m doing this work for someone who’s too scared to go look, and I’ll find someone else’s son or daughter, and I’ll help that person get closure,” and so, in that way they can keep that hope alive, because they all hope to find their family members alive, but when you think about it, searching for human remains is a lot cheaper than searching for people alive, which requires, like, going and staying in hotels, and going around to places, and, like it’s—and with this it’s like: get in a car, drive 45 minutes from Torreón, and you’re in a killing field, and there’s I don’t know how many of these, like, right now, I think they have probably over 20 operational sites where they’re exhuming, just in this area in Coahuila, around Torreón, so, I mean, yeah what’s going on around the country is—the last I heard there are, I mean, there’s at least 62 family groups like this, but probably many, many more…

I: Across the country, and…

D: Yeah, it’s it’s a new development in terms of social movements in Mexico, for sure, especially since Ayotzinapa, and it’s very, very powerful in terms of challenging official discourse on…, “The government is helping, the government is looking for people, the government is repairing the damage, the government is,” you know, “making things better, and these families are saying, “The government is only here because we’re here, they’re following behind us, and they’re only here because we’re doing this work, because if the families went out there finding all those human remains, the government would be, again, the bureaucrats, would be sitting at their desks in air conditioning, fucking the dog, let’s just say.

I: Because, Dawn, this form of loss is is the cruelest, no?, because there is nobody to mourn, the pain that or the loss never goes away, like it doesn’t conclude.

D: Yeah, it’s awful.

I: And yet, we also see this continuity between the Dirty war in the 70s and 80s, as you mentioned, the Argentina-Mexico, link although the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo have a different approach, right? And they are operating in this contradiction between getting closure and keeping the hope alive. Has anyone that you know have been found alive?

D: I recently found out about a case of someone who was disappeared in Torreón, and who was released, he was held for a few days, so… and, I think that, again, I think there’s a lot of cases that happened like that, where it’s like, in that case that I’m referring to, like, the people that disappeared this person, and this happened like two months ago, were state police, they were basically the SWAT team of the governor of Coahuila. You’re not going to go, you know, make an official complaint, because making a complaint is drawing more attention to yourself to the same state that just did that thing to you, or the message is, “Go home and shut the fuck up,” right?, like…

I: But through these groups we can say that that civil society is achieving a degree of agency?

D: I know in some places, for example, there’s rapid response teams, so if they find out that it was like a police perpetrated disappearance, they’ll immediately send people to basically go to the front gates of the police station and demand that person be released immediately, right? And these are borrowing some of the tactics of resistance that were used in Argentina and other places as well during the Cold War, and, yeah. But, in terms of the family members that I worked with, in Grupo Vida there hasn’t been, I mean, that’s the thing about it, it’s so devastating, right? There’s a sort of a therapeutic element to the searches, there’s a media element, like it does give them a lot of power and a lot of agency, but at the end of the day, when you ask people, like, what’s going on with the case of your daughter or son, they’ll usually say: “Nothing. No hay avances,” like, everything’s the same, right? So there’s also, on the other side, just this deepening, deepening, I mean, just the pain, I think, gets worse for folks, and it’s also intergenerational, I mean, it’s not just the parents, like, a lot of people who are disappeared, even though they were disappeared quite young, you know, early twenties, a lot of them had one or two children already, so there’s that sort of generation that’s, for those kids who, again, even more precarity, because they’ve lost often the primary breadwinner of their family, who are now learning of these crimes, and I have hope, anyways, like, that some of these youth will become, like, a new generation of fighters, like, the way we saw with Hijos in Argentina, for example, or in Guatemala.

I: So obviously before this complex panorama that you draw in your two books, the policy of the current government of “Abrazos, no balazos” or “Hugs instead of gunshots” is ridiculous, to say the least.

D: Yeah, I feel like AMLO campaigned against violence, and against state violence and militarization of the Drug war, and has continued with the same, essentially the same, policies, with the main difference being the creation of the National Guard.

I: And what are the implications of the National Guard?

D: Well, there’s a fiction right now that the national guard is civilian, right? That it will transition into being a fully civilian force within five years, but it’s just, it’s like they say in Mexico, it’s simulación, it’s not real, and I think, any of us who’ve seen the National Guard on the street know that, I mean, they’re guys in trucks with semi-automatic weapons standing up in the back of the truck, driving around in camouflage, right?, like… And it’s also that fiction that, like, somehow a civilian leadership is that much better, when you consider that what they’re talking about with that is… Federal Police, basically, which are, you know, deeply corrupt, and deeply militarized police force in Mexico.

I: Right, and also comes with the right the rising of migrants crossing the country and with the subcontraction of migrant contention to Mexico, no?

D: Exactly, exactly, which, I think, you know, paramilitarism—the 72 migrants that were disappeared and then found in that clandestine grave in San Fernando, Tamaulipas in 2010 were an early and very obvious indicator of what the strategy for containing migration looks like now in Mexico, and it looks like it’s paramilitarized, but that doesn’t mean that the state isn’t, one, sort of still actively supervising it, and, two, that there aren’t state elements of the state forces actively involved in in those processes of detention and massacre.

I: Está muy cabrón, Dawn, I’m super queasy. Is there anything you’d like to add to conclude?

D: Well, I guess I would just say that I have been, like, extremely bummed out, like, I’ve been pretty depressed with everything that’s happened with COVID, I feel like the response from the Mexican government has been extremely, extremely…

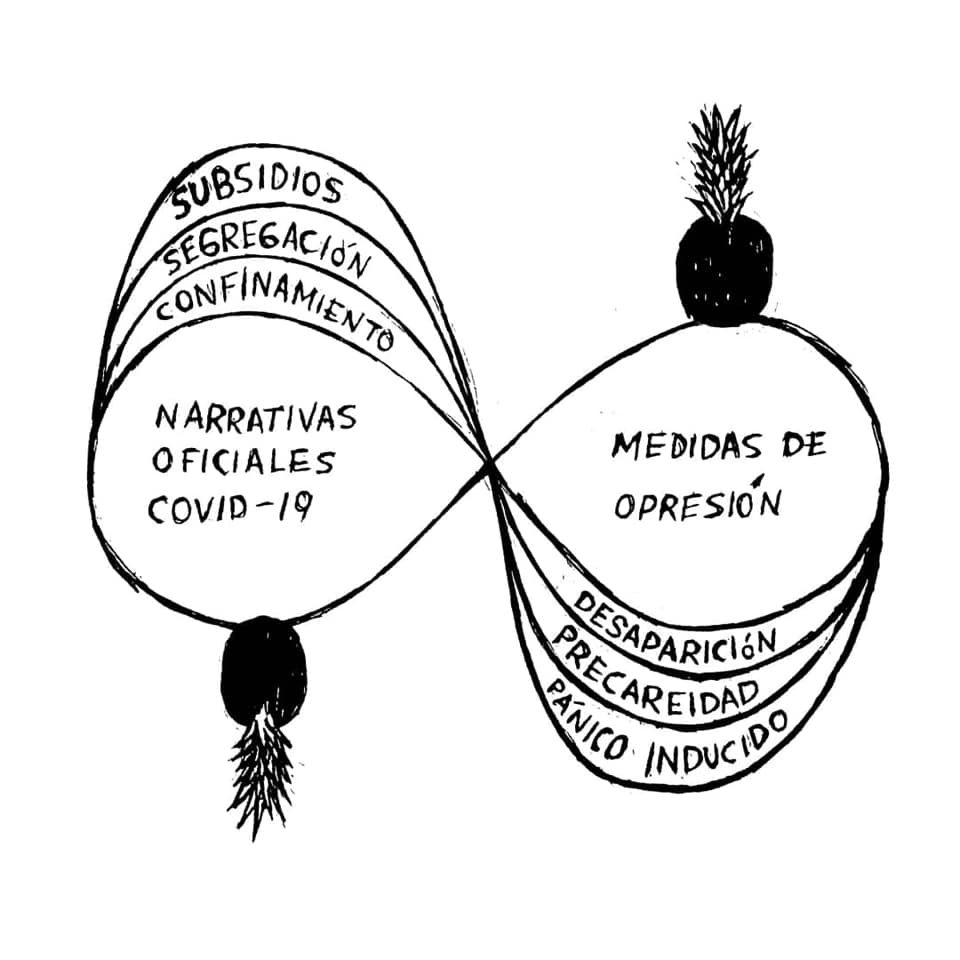

I: I would say, it’s outright a continuation of the social cleansing, very perverse.

D: Exactly, that’s how it feels, it just feels wicked, it just feels like, you know, the fact that people aren’t getting any support, any extra money when their business is closed, when they can’t go to work, it’s just like, “Fend for yourselves, guys, and if you eat well and whatever, you should be fine,” you know, like they keep saying, you know, “Most people are just gonna have like a light flu,” like they keep on kind of suggesting that it’s fine to just get it, you know, “Get it and stay home,” and whatever, and it’s like, the stories that I’m hearing from people on the ground do not match up at all with, like, the official line of what’s going on, and it does, it feels like a continuation, it’s just, it’s like utter contempt for the population, and those who have the resources to not expose themselves and not be vulnerable…

I: And to get the medicine and the tests…

D: You can get the medicine, you can get the test, you can get your [narcotic] drugs through like a boutique, like, app, so don’t worry about it but if you’re, like, buying [narcotics] on the street, or if you’re, like, not able to access a test, then it’s your own fault, right? It’s like, it’s a very similar criminalize the victim, shame the victim, and it’s state policy, that is at the root of what’s taking place. And the fact that, you know, that then the sort of falseness of saying, “The mexican government can’t afford to pay people to stay home,” and it’s like, but they can afford this massive military budget, new airport, for what tourists? Tren maya…

I: The cultural center…

D: Like, all of this big builds that are supposedly, like, you know, they’re these signature projects of López Obrador, that don’t have any clear economic path in this… in the COVID age, because there is not going to be that kind of tourism probably for quite a few years; are still the ones that are just receiving all the money and, like, the refineries, it’s like, still, this huge investment and, again, it’s like Cold War, infrastructure projects, and just letting people… but it’s beyond letting people die, it’s really administering a public relations campaign to normalize a level of suffering and death that is totally unnecessary, and that is totally preventable.

I: No, and it’s like it’s a clear continuation of the Neoliberal war and the austerity measures, you know, in the culture sector, and with education that is now being centralized on television, I really fear that that’s the end of public education, you know.

D: It’s very, yeah, it’s been a, yeah, it’s been definitely a very hard couple months, and, like, honestly, I have kind of checked out a lot of stuff, and like stopped following, you know, for example the video of El Mencho, like, I see that video and I’m like, “What is this?,” like the purpose of that video is to justify militarization, it doesn’t matter who’s showing it, it’s either, “Look, the government’s weak, we need more forces,” or, “Look, the organized crime is strong, we need more forces,” like whatever way you want to look at, but, at the same time, it’s like, I’m not, like, taking the time to forensically analyze or like, I just, I’m finding, I’m like finding it super hard to connect, because it’s just like totally, overwhelmingly horrible.

I: Yeah, I hear you.