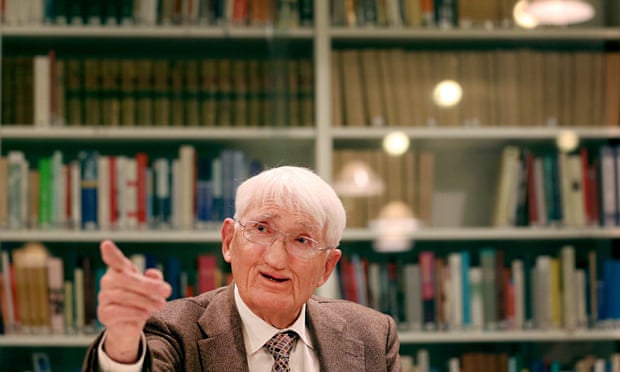

Interviewed by Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, Jürgen Habermas speaks about authoritarianism, populism, and new alt-right politicians and parties such as Marie Le Pen, Alternativ für Deutschland, Putin and Trump. Read the translation by David Gow in partial below, in full via Social Europe.

After 1989, all the talk was of the “end of history” in democracy and the market economy and today we are experiencing the emergence of a new phenomenon in the form of an authoritarian/populist leadership – from Putin via Erdogan to Donald Trump. Clearly, a new “authoritarian international” is increasingly succeeding in defining political discourse. Was your exact contemporary Ralf Dahrendorf right in forecasting an authoritarian 21st century? Can one, indeed must one speak of an epochal change?

After the transformation of 1989-90 when Fukuyama seized on the slogan of “post-history” as coined originally within a ferocious kind of conservativism, his reinterpretation expressed the short-sighted triumphalism of western elites who adhered to a liberal belief in the pre-established harmony of market economy and democracy. Both of these elements inform the dynamic of social modernisation but are linked to functional imperatives that repeatedly clash. The trade-off between capitalistic growth and the populace’s share – only half-heartedly accepted as socially just – in the growth of highly productive economies could only be brought about by a democratic state deserving of this name. Such an equilibrium, which warrants the name of “capitalist democracy”, was, however, within an historical perspective, the exception rather than the rule. That alone made the idea of a global consolidation of the “American dream” an illusion.

The new global disorder, the helplessness of the USA and Europe with regard to growing international conflicts, is profoundly unsettling and the humanitarian catastrophes in Syria or South Sudan unnerve us as well as Islamist acts of terror. Nevertheless, I cannot recognise in the constellation you indicate a uniform tendency towards a new authoritarianism but, rather, a variety of structural causes and many coincidences. What binds them together is the keyboard of nationalism and that has begun to be played meanwhile in the West. Even before Putin and Erdogan, Russia and Turkey were no “unblemished democracies.” If the West had pursued a somewhat cleverer policy, one might have set the course of relations with both countries differently – and liberal forces in their populaces might have been strengthened.

Aren’t we over-estimating the West’s capabilities retrospectively here?

Of course, given the sheer variety of its divergent interests, it would not have been easy for “the West” to have chosen the right moment to deal rationally with the geo-political aspirations of a relegated Russian superpower or with the European expectations of a tetchy Turkish government. The case of the egomaniac Trump, highly significant for the West all told, is of a different order. With his disastrous election campaign, he is bringing to a head a process of polarisation that the Republicans have been running with cold calculation since the 1990s and are escalating so unscrupulously that the “Grand Old Party”, the party of Abraham Lincoln, don’t forget, has utterly lost control of this movement. This mobilisation of resentment is giving vent to the social dislocations of a superpower in political and economic decline.

What I do see, therefore, as problematic is not the model of an authoritarian International that you hypothesise but the shattering of political stability in our western countries as a whole. In any judgment of the retreat of the USA from its role as the global power ever ready to intervene to restore order, one has to keep one’s eyes on the structural background – one affecting Europe in similar manner.

The economic globalisation that Washington introduced in the 1970s with its neoliberal agenda has brought in its wake, measured globally against China and the other emergent BRIC countries, a relative decline of the West. Our societies must work through domestically the awareness of this global decline together with the technology-induced, explosive growth in the complexity of everyday living. Nationalistic reactions are gaining ground in those social milieus that have either never or inadequately benefited from the prosperity gains of the big economies because the ever-promised “trickle-down effect” failed to materialise over the decades.

Even if there is no unequivocal tendency towards a new authoritarianism, we are obviously going through a huge shift to the Right, indeed a Right-wing revolt. And the pro-Brexit campaign was just the most prominent example of this trend in Europe. You yourself, as you recently put it, “did not reckon with a victory for populism over capitalism in its country of origin.” Every sensible observer cannot but have been struck by the obvious irrational nature not just of the outcome of this vote but of the campaign itself. One thing is clear: Europe is also increasingly prey to a seductive populism, from Orban and Kaczynski to Le Pen and AfD. Does this mean we are going through a period of making irrational politics the norm in the West? Some parts of the Left are already making the case for reacting to right-wing populism with a left-wing version of the same.

Before reacting purely tactically, the puzzle has to be solved as to how it came about that right-wing populism stole the Left’s own themes. The last G-20 summit delivered an instructive piece of theatre in this regard. One read of the assembled heads of government’s alarm at the “danger from the Right” that might lead nation states to close their doors, raise the drawbridge high and lay waste to globalised markets. This mood embraces the flabbergasting change in social and economic policy that one of the participants, Theresa May, announced at the latest Conservative party conference and that caused waves of anger as expected in the pro-business media. Obviously, the British prime minister had thoroughly studied the social reasons for Brexit; in any case, she is trying to take the wind out of the sails of right-wing populism by reversing the previous party line and setting store by an interventionist “strong state” in order to combat the marginalisation of the “left behind” parts of the population and the increasing divisions within society. Given this ironic reversal of the political agenda, the Left in Europe must ask itself why right-wing populism is succeeding in winning over the oppressed and disadvantaged for the false path of national isolation.

This interview was conducted by and first published in Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik. Translation by David Gow.

*Image of Jürgen Habermas via The Guardian