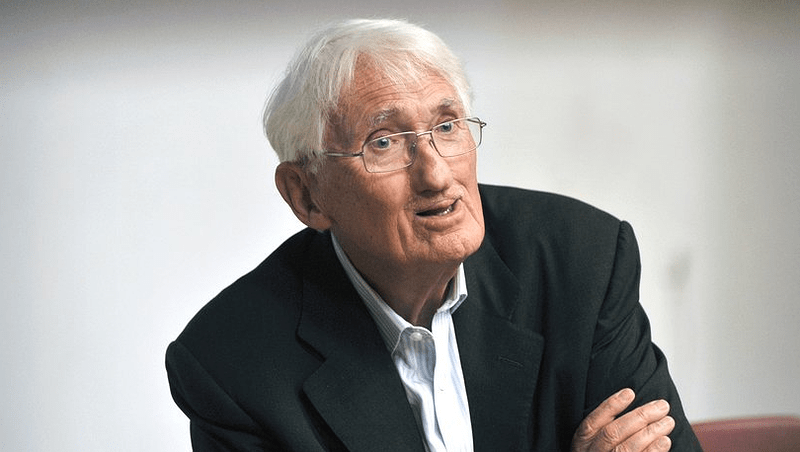

For Die Zeit, the internationally renowned philosopher Jürgen Habermas speaks with Thomas Assheuer about his views on the Brexit and hardships facing the European Union. Read the interview in partial below, or in full via Die Zeit.

DIE ZEIT: Mr Habermas, did you ever think Brexit would be possible? What did you feel when you heard of the Leave campaign’s victory?

Jürgen Habermas: It never entered my mind that populism would defeat capitalism in its country of origin. Given the existential importance of the banking sector for Great Britain and the media power and political clout of the City of London it was unlikely that identity questions would prevail against interests.

ZEIT: Many people are now demanding referenda in other countries. Would a referendum in Germany produce a different result from that in Great Britain?

Habermas: Well, I do assume that. European integration was – and still is – in the interests of the German federal republic. In the early post-war decades it was only by acting cautiously as “good Europeans” that we were able to restore, step by step, an utterly devastated national reputation. Eventually, we could count on the backing of the EU for reunification. Retrospectively too, Germany has been the great beneficiary of the European currency union – and that too in the course of the euro crisis itself. And because Germany has, since 2010, been able to prevail in the European Council with its ordoliberal views against France and the southern Europeans it’s pretty easy for Angela Merkel and Wolfgang Schäuble to play the role of the true defenders of the European idea back home. Of course, that’s a very national way of looking at things. But this government need have no fears that the Press would take a different course and inform the population about the good reasons why other countries might see things in completely the opposite way.

ZEIT: So, you’re accusing the Press of supinely kowtowing to the government? Indeed, Ms Merkel can hardly complain about the number of her critics. At least as regards her refugee policy.

Habermas: Actually, that’s not what we’re talking about. But I make no bones about it… Refugee policy has also divided German public opinion and Press attitudes. That brought an end to long years of an unprecedented paralysis of public political debate. I was referring to this earlier, politically highly charged period of the euro crisis. That’s when an equally tumultuous controversy about the federal government’s policy towards the crisis might have been expected. A technocratic approach that kicks the can down the road is attacked as counter-productive all over Europe. But not in the leading two daily and two weekly publications that I read regularly. If this remark is correct then, as a sociologist, one can look for explanations. But my perspective is that of an engaged newspaper reader and I wonder if Merkel’s blanket policy of dulling everyone to sleep could have swept the country without a certain complicity on the part of the Press. Thought horizons shrink if there are no alternative views on offer. Right now, I can see a similar handing out of tranquillisers. Like in the report I’ve just read on the last policy conference of the SPD where the attitude of a governing party to the huge event of Brexit that must objectively be of consuming interest to everybody is reduced – in what Hegel would have called a valet’s perspective - to the next general election and the personal relations between Mr Gabriel and Mr Schulz.

ZEIT: But hasn’t the British desire to leave the EU national, homegrown reasons? Or is it symptomatic of a crisis in the European Union?

Habermas: Both. The British have a different history behind them from that of the continent. The political consciousness of a great power, twice victorious in the 20th century, but globally in decline, hesitates to come to terms with the changing situation. With this national sense of itself, Great Britain fell into an awkward situation after joining the EEC for purely economic reasons in 1973. For the political elites from Thatcher via Blair to Cameron had no thought of dropping their aloof view of mainland Europe. That had already been Churchill’s perspective when, in his rightly famous Zurich speech of 1946, he saw the Empire in the role of benevolent godfather to a united Europe – but certainly not part of it. British policy in Brussels was always a standoff carried out according to the maxim: “have our cake and eat it”.

ZEIT: You mean its economic policy?

Habermas: The British had a decidedly liberal view of the EU as a free trade area and this was expressed in a policy of enlarging the EU without any simultaneous deepening of co-operation. No Schengen, no euro. The exclusively instrumental attitude of the political elite towards the EU was reflected in the campaign of the Remain camp. The half-hearted defenders of staying in the EU kept strictly to a project (?) fear campaign armed with economic arguments. How could a pro-European attitude win over the broader population if political leaders behaved for decades as if a ruthlessly strategic pursuit of national interests was enough to keep you inside a supranational community of states. Seen from afar, this failure of the elites is embodied, very different and full of nuances as they are, in the two self-absorbed types of player known as Cameron and Johnson.

ZEIT: In this ballot there wasn’t just a striking young-old but a strong urban-rural divide. The multi-cultural city lost out. Why is there this sudden split between national identity and European integration? Did Europe’s politicians underestimate the sheer persistent power of national and cultural self-will?

Habermas: You’re right, the British vote also reflects some of the general state of crisis in the EU and its member states. The voting analytics point to the same kind of pattern that we saw in the election for the Austrian presidency and in our own recent state parliament elections. The relatively high turnout suggests that the populist camp succeeded in mobilising sections of previous non-voters. These can overwhelmingly be found among the marginalised groups who feel hung out to dry. This goes with the other finding that poorer, socially disadvantaged and less educated strata voted more often than not for Leave. So, not only contrary voting patterns in the country and in the cities but the geographical distribution of Leave votes, piling up in the Midlands and parts of Wales – including in the old industrial wastelands that have failed to regain their feet economically – these point to the social and economic reasons for Brexit. The perception of the drastic rise in social inequality and the feeling of powerlessness, that your own interests are no longer represented at the political level, all this forms the background to the mobilisation against foreigners, for leaving Europe behind, for hating Brussels. In an insecure daily life ‘a national and cultural sense of belonging’ are indeed stabilising elements.

*Image of Jürgen Habermas © Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty Images