Writing for the Institute of the Present, art historian Daniel Grúň reflects on Slovak avant-garde artist Július Koller and the extensive personal and artistic archive he left behind when he died in 2007. In an innovative move, Grúň approaches Koller’s archive not as a passive collection of documents but rather as an active and ongoing performance. Read an excerpt from Grúň’s piece below, or the full text here.

I will go on to describe the processes of self-historicising in the work of Július Koller (1939–2007), whose archive is the one I am most closely acquainted with. In this case work and archive are very closely interconnected: that part of the artist’s production which is now internationally distributed as individual artworks is only the jutting tip of an iceberg whose body remains submerged. The voluminous system of notes, documents and printed pieces becomes unmanageable if one does not know the logic of its arrangement. I am trying here to elucidate the complex link between work and archive by focusing on Koller as performer and defining the archive as the extended body of the artist. Consequently the archive—extended body of the artist—, dispersed in fragments of another medium and, as it were, in the limbs of his archival “body,” fulfils its futurological mission. Philip Auslander has used the term “performativity of documentation” to define documents which are not simply an indicative access point to a past event: rather, these documents themselves are performances which fully reflect the sensibility or the aesthetic project of the artist and for which, at the moment of reading them, we become an active public. Therefore the unique presence of performance in real time, its disappearing “now,” is not necessarily in contradiction to the archive, whose logic is enduring repetition. Rebecca Schneider points out that if we perceive performance as an act of enduring and repeated manifestation, we need not approach it as something that vanishes after its completion. Precisely in the work of artists such as Július Koller, the document or object does not merely contain isolated relics of performance: these documents anticipate and generate further performances. With the three-letter acronym UFO, in 1970 Koller launched his mechanism of designation, the Universal-Cultural Futurological Operations. I would associate this practice with the notion of performative archive by which I understand the assembling of works, documents and other ephemera to form a system of language, where every individual document is part of universal activity of questioning. In this complex system every signifiant has its signifié, and often there are multiple designated entities. Accordingly, under a single name a concept is found in variable versions. So as to keep track of the broad range of his work, Koller began systematically writing chronological registers, which he gradually adapted and refined. His system of language enables us to appreciate the extensive range of his activities, working methods, interventions and records as part of the permanent linguistic activity defined by the artist, linking apparently divergent spheres of his work: painting, action, conceptual art.

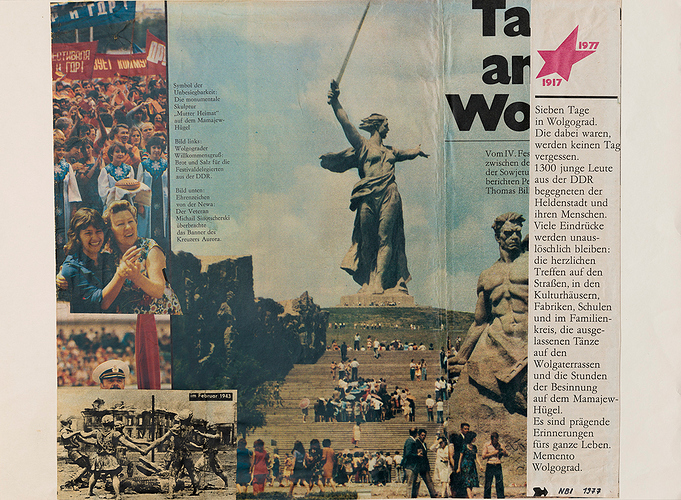

Image: Július Koller, Untitled, NBI 1977. Via Institute of the Present.