In the current issue of Bookforum, Charlotte Shane reviews three recent books that grapple with the death-denying tendencies of modern Western societies: From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty; You Can Stop Humming Now: A Doctor’s Stories of Life, Death, and in Between by Daniela Lamas; and With the End in Mind: Dying, Death, and Wisdom in an Age of Denial by Kathryn Mannix. Shane lauds these authors for their frank denunciations of medical practices that prolong life at the expense of a dignified, humane death. But she challenges the notion that in modern culture, death is swept under the rug. Instead, Shane argues that death is pervasive and in-your-face—from hyper-violent movies to suicide threats on social media—but we just don’t care to address the structural sources of this suffering. Here’s an excerpt from the review:

Moving through death is a nonnegotiable component of being alive: Soil is made of remains, we eat dead things to stay alive, our own passing is inescapable, and all that. But the particular way in which we are now steeped in death can be attributed to downward mobility and a pervasively dismal quality of life. Farmers, impoverished and relatively isolated, kill themselves at twice the rate of veterans. Researchers ascribe the frequency of middle-aged suicides to financial insecurity. Functionally indentured with no hope of a decent wage, recent college graduates attend the funerals of friends who couldn’t afford basic medical assistance—especially mental-health care. These deaths are all preventable, but prevention is not a priority of those in power, which means the numbers rise.

In her new book, From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death, a survey of how various cultures handle, understand, and mourn their dead, insistently chipper mortician Caitlin Doughty cites scholar Elizabeth Harper, who has observed that cults of the dead are “most noticeable during times of strife,” especially among those who “lack access to power and resources.” Harper is referring to Neapolitans who venerated anonymous, exhumed graveyard skulls shortly before the turn of the nineteenth century: petitioning them for favors, building shrines, and otherwise treating them like spiritual relics—much to the consternation of the Catholic Church. But her analysis applies across time and place; Doughty sees the same dynamic at work in present-day Bolivia, where a matriarchal culture of skull appreciation thrives. It might also explain some of what’s happening among disenfranchised young(ish) adults on social media, where jokes about yearning for death are relentless. Few of us have access to skulls, but most of us have access to skull emoji.

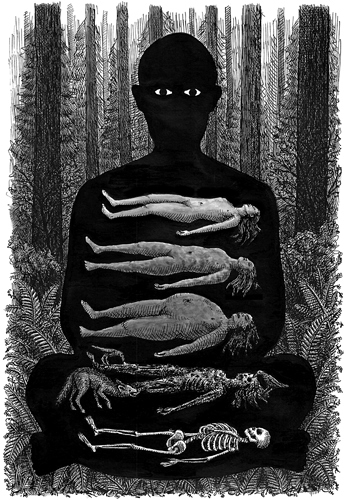

Image: Illustration by Landis Blair for Caitlin Doughty’s From Here to Eternity, 2017. Via Bookforum.