Image: Homai Vyarawalla with her smaller Speed Graphic camera on her shoulder.

by Skye Arundhati Thomas

In rare color footage from the morning of August 15, 1947, the day of Indian Independence, the sun fills up the screen in a brilliant blaze as a ceremonial procession carries forward the famous protagonists of the film: Governor-General Louis Mountbatten and his wife, Edwina.1 Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru has just been sworn in as the first prime minister of the country and the parade begins from the steps of Parliament House, New Delhi, in a flurry of dark horses braided with red and gold. Quite suddenly, a woman wearing a white sari bursts into the corner of the frame; slung over one shoulder is a camera, another one in her hand. It is as though the whole scene shifts focus and she is at its center, pulling everything toward her, like the opening credits to a story about her life.

In December 1913, the same year that Tagore won the Nobel Prize for Gitanjali and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was arrested for marching with Indian miners in South Africa, Homai Vyarawalla was born to a Parsi family in Navsari, Gujarat. She began her career as a photojournalist in the early 1940s, and her career spanned the most formative years of India’s recent history: the ten years leading up to its independence from the British Empire, and the first twenty of its new status as a Republic. Homai met Maneckshaw Vyarawalla at a railway station in Mumbai (Bombay at the time) in 1924 and they were married shortly after. He was an aspiring photographer in possession of a camera, and together, they began to teach themselves to photograph, primarily by experimenting with the machine and leafing through old issues of British photography journals and the American magazine Life. At the start of her career Vyarawalla published under her husband’s name, on assignment for the Illustrated Weekly of India and the Bombay Chronicle. Her earlier work almost entirely consists of photographs of women: delicate images of women lounging over rocks in a murky stream, sculpting at the J. J. School of Arts, or drinking toddy over picnic blankets covered in needlework.

In the early 1940s, both Homai and Maneckshaw Vyarawalla were employed by the British Information Service (BIS). The BIS had been set up in New Delhi in 1942, and it was the official outpost of the Ministry of Information, an institution primarily involved in the production of propaganda. Looking to acquire new photographers from the subcontinent, the director came upon the Vyarawallas, and Maneckshaw was employed as Bureau-Chief Photographer, in charge of the studio and its dark rooms, while Homai was employed as an official photographer under their license. The BIS was an Imperial institution, and under their employ, the Vyarawalla’s were given the same status as British photographers of the time, a rare occurrence, as the BIS rarely sought Indian involvement. Homai’s work thus took a fundamental turn; all of her photographs were thenceforth political. On her first day as a photographer for the BIS, Homai marched up to the director and demanded to be paid one rupee per photograph, as she had been while she published under her husband’s name. Her request was granted without hesitation.

Homai’s classmate at the J. J. School of Arts and her favorite model, Rehana Mogul, posing for the camera at a women’s picnic. Bombay, late 1930s Photo: Homai Vyarawalla.

Perhaps one of Homai Vyarawalla’s most interesting qualities was her reluctance to self-mythologize. When asked why she took up photography, she replied, “It was just a job.” When asked about what influenced her work, she said again, “It was just a job.”2 When asked about the historical significance of this job, whether she ever felt the burden of its representation, she admits to a certain innocence: she herself could have never known what the images would amount to. In a 2011 interview conducted by Hans Ulrich Obrist during the Khoj Marathon in New Delhi, a year before Vyarawalla’s death, Obrist repeatedly asks her to generate a better response than it was just a job. The Khoj Marathon signified a noteworthy moment in Vyarawalla’s life; until a few years before then, she had lived in complete obscurity. Upon her “rediscovery” by academic and filmmaker Sabeena Gadihoke, Vyarawalla was brought back into the spotlight—and considered in a different manner than she had been before. Her photographs were evaluated as art objects; Gadihoke proceeded to curate, together with Vyarawalla, three major retrospectives of her work across India and two in New York. Vyarawalla remained cool and composed in the face of Obrist’s questions; she maintained her position.

For nearly two decades before her death, Homai Vyarawalla lived entirely by herself. She was her own handyman, stitched her own slippers, and made her own clothes—cotton shirts and loose-fitting trousers, leather sandals with knots at the toe. If she caught sight of rubbish on the street, she would rush out with a coarse jhadu (broom) and sweep it right up, lighting big fires for the neighborhood to see. In the cool dusk of the evening, children played cricket in front of the gate and Vyarawalla read the day’s newspapers in the shade of a tree. She enjoyed sas-bahu3 soaps on TV and cooking elaborate meals. She made her own furniture, strikingly modernist pieces in teak and iron.

In Anik Gosh’s film Homai Vyarawalla (2006), the camera slowly pans across Homai’s home.4 In the corner of a room rests an easel carved from wood, upon which are two photographs placed side by side. The first is a portrait of her deceased son Farouq Vyarawalla, and the second is a picture of Jawaharlal Nehru hugging his sister Vijaylaxmi Pandit—these are her favorite photographs, she says.

This is Vyarawalla’s proximity to history: in her sparsely decorated home, upon a pedestal, the memory of her son rests next to that of Nehru.

Mountbatten among the jubilant crowds outside the Parliament House on August 15, 1947. Photo: Homai Vyarawalla.

Homai Vyarawalla is the perfect protagonist: the only woman in her profession, fierce and independent, full of humor and a lightheartedness that is immediately affable. That she was the only woman is an easy thing to pounce upon, from which to glean more detail about her person and life. It is to place her in a position of compromise, of struggle—the ultimate disadvantage of being the only one of your gender in most rooms you occupy. There is another way of approaching this, and perhaps one that is more certain of its premise: that the slight invisibility granted to Vyarawalla by her gender becomes one of the most powerful ways to read her work. Hers becomes a narrative of perseverance, of having a different gaze than the rest; of her lens being met with the gaze, too, of her subjects—identifying, as they often did, the only woman in the crowd. Early on in her career, one of her male colleagues nicknamed her “Mummy,” a name she was happy to encourage, because it desexualized her. It was also a way for her male contemporaries to place her into a role with which they were familiar and could thus negotiate. One of the ways in which Vyarawalla was able to maintain her independence was through dress; she never adopted any Western styles, always wearing either a sari or salwar. She wore her dupatta across her body, its two ends folded into a knot by her side—a certain clue; here was a woman with busy hands. By asserting her nationalism through dress, she was able to maintain her independence without it being judged as a “corruption,” a sentiment applied by the Indian patriarchy to women who choose to do otherwise. Vyarawalla was clever; she knew which battles to pick.

Vyarawalla was also, as stated in a May 14, 1951 article in the New Statesman, “efficient and unobtrusive.” She was patient; she waited for all the other photographers to have their turn, staying at the scene longer than them. She was thus able to capture her subjects at moments that were more private, more intimate. They trusted her. She shared a friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, who once, after noticing a foreign male delegate dismiss her for directing him where to stand, linked his arm into hers and suggested they go for a walk. They stopped to admire the Mughal architecture of Parliament House, its painted ceilings. “When Nehru died I felt like a child that had lost her favorite toy,” she said.5

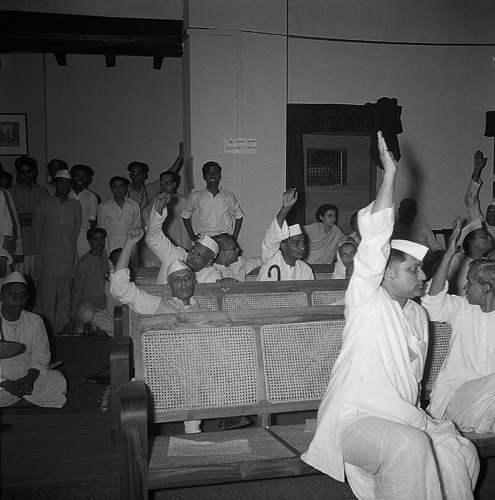

Jawaharlal Nehru voting for the motion to ratify partition. Indira Gandhi, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, and Govind Ballabh Pant are seen in the background. June 1947. Photo: Homai Vyarawalla.

With Mahatma Gandhi too, she persevered. He was indeed a difficult subject to photograph, suspicious of photographers and often inside dimly lit rooms. Most of all, he disliked the flash, and once said to a large crowd about Vyarawalla, “This girl will not rest until she makes me blind!”6 But she was persistent, and in fact grew fond of Gandhi and became a firm believer in his politics. She respected him, and as a gesture of her faith, she always photographed him from a low vantage, as if we, the viewers of the image, must look up at him.

A 1961 article in The Current had the headline: “India’s best-known woman photographer too missed the WORLD’S GREATEST NEWS PICTURE.” Inside the small column is a photograph of a young Vyarawalla, hair cut close to her face, wearing a simple salwar and holding a camera cradled close to her chest, index finger resting on the shutter release. This photograph that never got taken has become an integral part of the posthumous mythology of Homai Vyarawalla, albeit one that she did not care to fashion herself. The title refers to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, killed by four bullets through the chest at point-blank range, just as he was exiting that evening’s prayer meeting. There were no photographers present that day and the only record of the event is Gandhi’s own bloodstained dhoti that now hangs in a glass vitrine at the Gandhi Memorial Museum in Madhurai, a museum that receives almost ten times the number of annual visitors than its larger, more monumental counterpart in New Delhi. They come for the dhoti, a security guard told me. For some imprint of the Mahatma to stick perhaps, to lay claim on their bodies?

Although she did not make it to the prayer meeting that evening, some of Vyarawalla’s most famous photographs are those of Gandhi’s funeral. She hiked up her sari and climbed over a drainpipe at Birla House to catch a glimpse of the pyre—her camera panning across the crowd to find the spot decorated with marigolds, a fiery orange silenced by the black and white tones of her camera. Vyarawalla is very particular about her description of the day, and she recounted, with great distaste, how people ate aloo tikki and chaat on the funeral ground, opening up their tiffins to share, treating the event as though it were a carnival.7 This was a rather different impression to the one that Vyarawalla’s international contemporaries had, as Gandhi’s funeral was one of the most photographed events of that century. Present on the day were the famous photographers Margaret Bourke-White and Henri-Cartier Bresson. Bourke-White wrote in her biography of the incredible flames that grew so large as to lash out at the crowds. She wrote about the mud and the dust, the unbearable heat; in effect, she wrote of a sensational event.8 Vyarawalla, instead, dryly remarked on the festival food.

In BBC footage of the funeral, a somber voice-over announces, “Ashes are all that remain of the man who represented India’s finest aspirations. As the last religious rites are performed, a nation gives itself up to grief.”9 The footage is indeed incredible: planes shower streets with saffron petals, Louis Mountabatten and his family sit cross-legged on the ground, their finely pressed clothing browning in the mud, and the Indian cavalry, mounted on horses, struggles to control the large crowd, which chants in unison, “Mahatma Gandhi Zindabad” (Long live Mahatma Gandhi).

The first unfurling of the flag at Red Fort by Prime Minister Nehru. August 16, 1947. Photo: Homai Vyarawalla.

Vyarawalla was, in effect, engaged in the documenting of a subaltern history—one that relied heavily on individuals, on men, to shape it. And the Mahatma was a major catalyst in the writing of such a history, addressed most often as “father of the nation.” Men like Gandhi dominate the narrative, while other simply followed. These are not men who can be easily criticized, as their position (and aspiration) is so closely linked to that of the nation’s own. It is as though the idea of India itself cannot be divorced from their permanent representation, stamped hard onto the metal of our coins, ink-printed darkly onto our notes. Crowds are photographed as blurs, bodies blending into each other to become a single unit, one organism—individuals towering over them from podiums. Images like these create their own mythology, and in the collective memory, pieces of this type of historical narrative have to fit together perfectly. Perhaps this is why the photograph of Gandhi’s assassination, the one that never got taken, hangs over the posthumous narrative of Homai Vyarawalla—as though entangled within the aspiration the Mahatma represented is her own.

I am writing this in the library at SOAS, School of Oriental and African Studies, in the heart of Bloomsbury, London—around the corner from a rather misguided statue of Gandhi, which rests at the center of Tavistock Square. I walk past the statue often, and each time, I take a moment to look up at his face, to find his eyes, as though I must in some fashion confront his presence. The statue is usually decorated with flowers or small notes, candles too, that sputter and die fast in a city that is always windy. I have watched as people, so moved, cry in front of him. I have also watched as pigeon shit, indiscriminate, encrusts its surface. Gadihoke once brought Homai Vyarawalla for a visit to London, and Homai, wrapped tightly in a Kashmiri shawl, walked up toward the statue—it doesn’t even look like him, she said, he is not even wearing his glasses, she said, laughing and quietly turning away.

×

NOTES

1 As shown by Sabeena Gadihoke in Institute of South Asian Studies Seminars, The Many Lives of Homai Vyarawalla: Revisiting a Historial Archive - Part 1 (15 July 2015) →.

2 Khoj Studios, Khoj Marathon: Homai Vyarawalla, June 16, 2012 →.

3 A populist, formulaic genre of TV soaps in India, where the drama turns entirely on the jealous and scheming relationships of mothers-in-law (Sas) and daughters-in-law (Bahu).

4 Homai Vyarawalla. Directed by Anik Gosh. Produced by C. S. Lakshmi, 2006 →.

5 As quoted in the obituary by Haresh Pandiya, “Homai Vyarawalla, Pioneering Indian Photojournalist, Dies at 98,” New York Times, January 28, 2012 →.

6 As quoted in Sabeena Gadihoke, Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2010), 82.

7 As discussed by Sabeena Gadihoke in Institute of South Asian Studies Seminars, July 15, 2015.

8 See Margaret Bourke-White, Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1949).

9 ARCHIVE British Pathé, Funeral of Gandhi 1948. February 9, 1948 →.

All images courtesy of HV Archive/The Alkazi Collection of Photography.